Five Questions with Michael Smith |

|

In advance of his sixth solo exhibition at Nicholas Metivier Gallery, The Eye of the Storm, we asked Michael Smith a few questions about the inspiration for his latest body of work.

|

|

|

How has your personal experience of place influenced your current practice? |

|

|

I was born in Derby, England and immigrated to Montreal in my late twenties. The experience was quite dramatic. I went from a place where winter emerges slowly from the ground to a place where suddenly, during the fall, arctic air pours down from the north. The severity of the Canadian climate and its expanse of land still surprises and engages me.

My practice is informed by my early experiences and education including visits to major galleries and museums in Europe. The English and European landscape paintings I encountered during this time continue to influence me. Years later, hiking in the Canadian landscape, particularly in Newfoundland, encouraged me to express a more physical sense of place in my work.

Canadian abstract painters (especially the Quebec Automatistes), the paintings of American lyrical abstractionists like Joan Mitchell, and Canadian artist Paterson Ewen, have helped me understand how painting can express a physical presence of the land without adhering to traditions of representation.

|

|

|

| Michael Smith, Ice Fulcrum, 2018, acrylic and ink on paper, 16 x 22 in. | |

|

Works in this exhibition draw specifically on subject matter related to the Franklin expedition of 1845. How did this new series begin? |

|

|

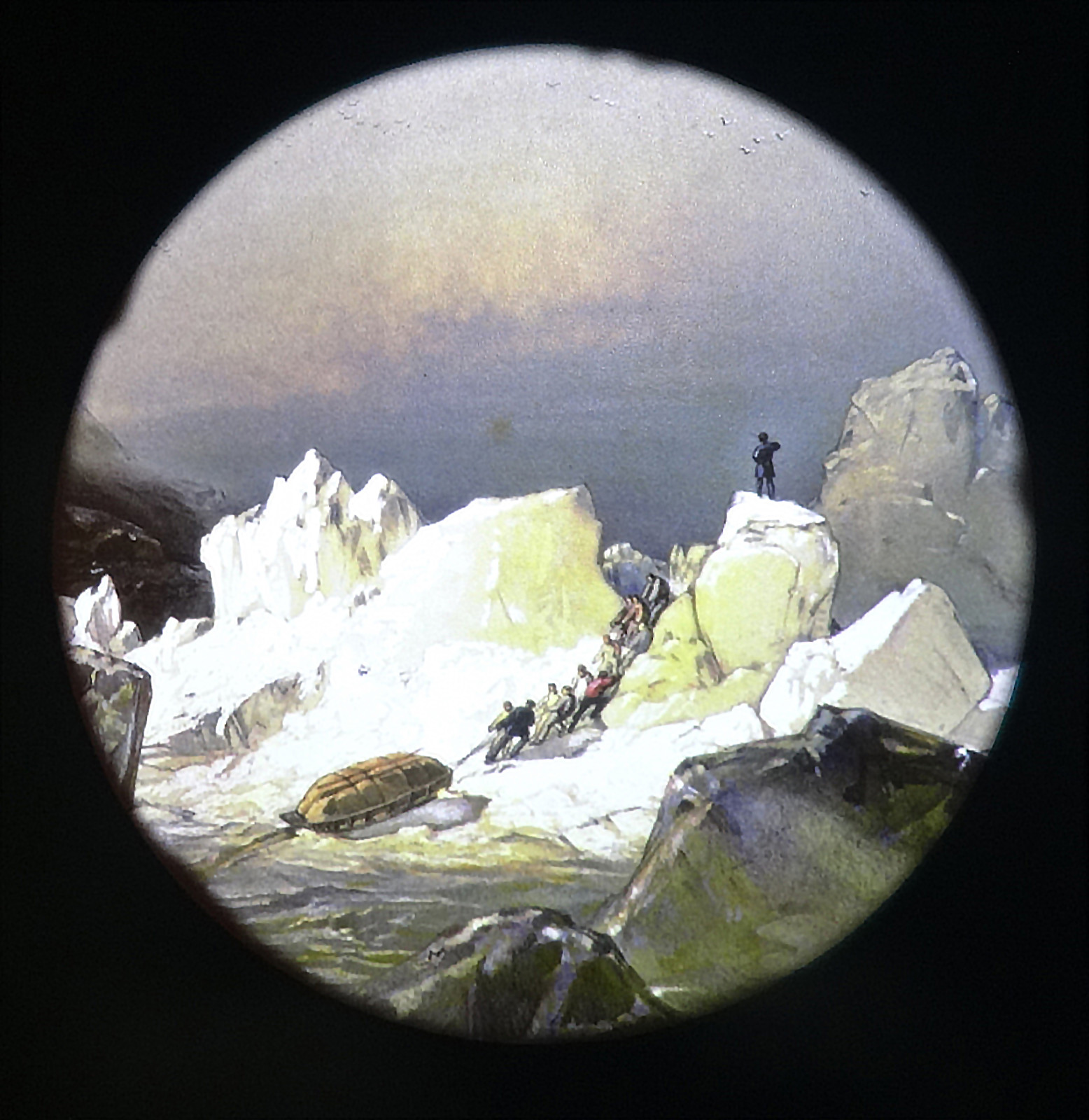

Last winter, I was invited by The Beaverbrook Art Gallery to spend a month working in the new Bruno Bobak studio alongside their collections. During this time, I was drawn to a maritime painting by George Chambers titled, The Crew of HMS ‘Terror’ Saving the Boats and Provisions on the Night of 15th March (1837), 1838. I was also given access to the Beaverbrook’s archives where I found two related watercolours by William Smythe. Chambers’ painting would likely have been influenced by these works.

Although the HMS Terror represented in Chambers’ painting recalls one of its early arctic expeditions, it was the ship’s plight during the Franklin voyage that fired my imagination. As I worked on many studies and improvisations, I felt as though the museum was a laboratory for the imagination rather than a repository for historical works. The narrative of the Franklin expedition became more and more intriguing to me adding to my research about shipwrecks, storms, and other maritime misadventures.

|

|

|

| George Chambers, The Crew of HMS ‘Terror’ Saving the Boats and Provisions on the Night of

15th March (1837), 1838, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 83.8 cm, collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery

| |

|

| Watercolour by George Smythe, Collection of the Beaverbrook Art Gallery

| |

|

| Michael Smith, Rogue, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 76 x 94 in. | |

|

You have painted seascapes throughout your career. What is it about this subject that keeps you interested and engaged? |

|

|

I lived by the sea as an art student in Cornwall, England. I remember watching a trawler smash to a thousand shards of wood and steel as it was being gently raised and lowered onto rocks by a gradual swell. Years later, I saw a photograph in a small museum in North Sydney, Nova Scotia of a rogue wave almost capsizing a vessel full of solders on their way to fight in World War II. The simultaneous majesty and terror of the elements leads to my continued fascination with the ocean.

|

|

|

| Michael Smith, Danger Waters #1, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 in. | |

|

This exhibition includes tondos, a recent format for your work. Why did you explore a circular canvas shape for this project? |

|

|

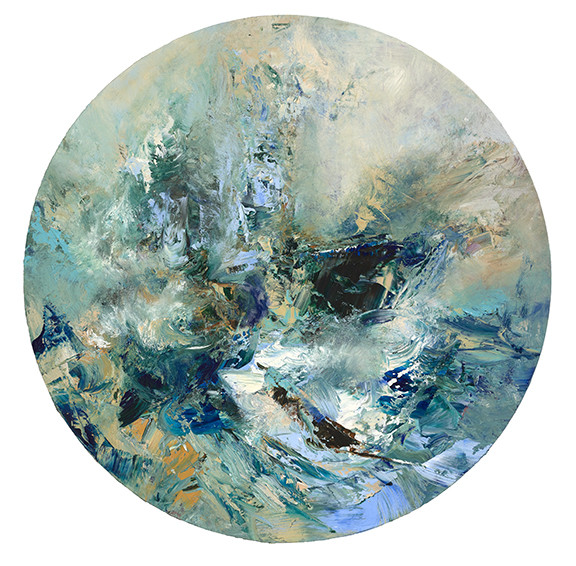

I began experimenting with a circular format a few years ago. I revisited large sections of early paintings, transforming them into tondos to challenge my notions about composition and engage with associations of the globe and sphere. I also studied early tondo paintings by 15th and 16th century artists. Alex Janvier’s contemporary circular abstract paintings with symbolic references exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada were highly inspirational. Tondos require a sophisticated geometric structure and after many drawings and works on paper, I became confident working in this new format.

The tondo paintings in this exhibition reference magnifying glasses, compasses, maps, 18th century constellation charts, magic lantern slides and other materials related to voyages of circumnavigation.

|

|

|

| Image: Magic Lantern Slide | |

|

| Michael Smith, Of Gifts and Destructions, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 60 in. diameter | |

|

In his 2016 essay, Memory Current, Robert Enright wrote, "In Smith's hands, a landscape is a repository for memory (the past) and a site for making (the present)". Is this notion addressed in the latest paintings? |

|

|

I am aware of the crossover of past and present time in certain themes that my paintings address. While the Franklin expedition took place nearly two centuries ago, the desire to journey and explore today is as strong as ever before.

Painting, for me, is a physical act of engagement. When you look at my paintings it is apparent that the materiality is related to the subject of the paintings. The mediums and pigments reveal the traces of their making – a kind of unedited strata of layers. I see the very act of painting as a kind relay of the past to the present and to the future. These coalesce in the present, in the making of the work.

|

|

|

| Michael Smith, Illusion Horizon, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 60 in. diameter | |

|

MICHAEL SMITH: THE EYE OF THE STORMFebruary 7 - March 2, 2018 Opening Reception: Thursday, February 7, 6-8 PM For more information on this exhibition, click here.

|

|

|

|

|