Welcome to our Letter from Berlin!

How do you document an exhibition that is in itself a work of art? This is the theme of our newsletter, as we focus on our two new platforms, exploring our extensive archives and its contemporary digital equivalent.

Esther Schipper speaks about Cologne in the 1990s, in a conversation with Brigitte Jacobs van Renswoun conducted for a special edition of the journal Sediment.

Our Head of Content Isabelle Moffat writes about the experience of visiting exhibitions in person or remotely and the value of the archive.

We highlight our cooperation with Zapp Magazine, a pioneering international art magazine on video produced between 1994 and 2007. We begin with footage from Julia Scher’s lecture/performance Safe & Secure with Julia, presented in 1994 at the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne.

In the Reading Corner a project focuses on the photographers documenting art. We also want to draw your attention to OneStar’s release of pdfs of artists' books.

If you missed our Associate Director Jonas Kriszeleit’s appreciation of Karin Sander’s kitchen piece, Isa Melsheimer’s Message From Home or the most recent Guess Whose Studio, you can find links below.

All our digital content can now be found at Continuity. Bringing together our digital content in one place, the new platform features exclusive content from our artists. Conversations, book readings, film screenings, presentations of virtual exhibitions, essays, and much more.

Read this in good health |

|

|

Thirty Years: Past and Present

|

|

| Exhibition view: Liam Gillick, McNamara, Schipper & Krome, Cologne, 1994

Photo © Lothar Schnepf

| |

|

This week we are inaugurating several new features on our website.

Continuity, our new digital platform, features a variety of news, messages and online stories by our artists and the gallery staff. It also hosts our weekly e-mailing, Letter from Berlin.

We have added Selected Works section to each artist’s page on our website. It gives an overview of major works, spanning throughout the entire careers of the represented artists.

A separate section integrates of all historical exhibitions at Johnen Galerie since 2004.

In the course of last year’s thirtieth anniversary of the gallery’s founding in Cologne in 1989, extensive archive material was published on the gallery’s website. The online-accessible exhibition history documents over 230 internal gallery and countless external institutional exhibitions. |

|

|

I lived in New York in the 1990s but often came home to Hamburg for Christmas or summers. During these visits I frequently went to the Kunstverein where I had seen many exhibitions before I left to study in the US. Did I see, say, General Ideas’s Fin de Siècle in 1992 or the 1993 group exhibition Backstage during one of these visits? Would I have made a point of going, had I known they would be regarded as landmarks?

These are questions not just for my art historian self. Since I began working at the gallery, I have asked myself this question about many of our artists’ exhibitions: I was in town, I knew the artist, some of their friends, or usually followed the program of an institution or gallery—why didn’t I stop by, or did I? Sometimes I half-expected to see my younger self peering out at me from exhibition views.

For artists whose exhibitions are not a selection of discrete objects but who consider them a critical medium in itself, the documentation of exhibits has been a problematic issue. How can you capture an experience, a state of conceptual flux, the relationship of objects, a discursive stance? Images of the situation they had created could only function as snapshots or in a conceptual framework as symbolic representations of what had occurred. Drawing on a legacy of conceptual and performance-based works that were not supposed to take or be defined by permanent form, nor, in the case of performance, were its traces considered art works as such, some artists resisted the very notion of documenting their exhibitions at the time.

These artists have long been relieved to find that someone did. In some cases, they began a process of archival self-documentation that became an integral part of their practice—it’s perhaps ironic that the archive was a major theme at the very moment that the function and form of the exhibition was radically reformulated.

An archive needs an inordinate amount of care, scrupulous attention and continuous upkeep. Its ephemera give a tactility and – must we admit it – aura to past events. The idea of the physical object as mnemonic emotionally charged device has waxed and waned yet continues to have a hold on us. Now digitalized, there is still a glimpse of its material existence that we gather from a scan, preferably one that by its un-photoshopped lack of seamlessness retains a highly mediated notion of immediacy.

This month we are looking at art remotely, navigating virtual spaces, visiting museums from a distance, screening encounters. But there is a longing for the spaces of art institutions and the communality of experiencing art together. I can’t wait for museums to open again, to visit galleries, to observe with the specificity of the human eye and its physiological glitches: the way color, texture, and shape work together, how the slight movement of the head changes everything. It’s an experience that machine-digested data transformed from ones and zeros to pixels and smoothed into an image cannot replace. Another irony.

Yet, for the works that no longer exist—for exhibitions that themselves constituted a paradigmatic shift of what an exhibition could be—there is for now no better way to encounter them than as archive: a rich depository of ephemera, images, texts, first-hand reports, and sometimes artist’s voices. Except, of course, for the next exhibition.

We hope you enjoy visiting the history of the gallery’s exhibitions on our website.

– Isabelle Moffat

|

|

|

A Conversation About Cologne in the 1990s with Esther Schipper

|

|

In 2018 Brigitte Jacobs van Renswoun interviewed Esther Schipper for a special edition of Sediment, the journal published by the Central Archive for German and International Art Market Research (ZADIK). Recollecting the early years of the gallery's history, the conversation touched upon the vibrant atmosphere in Cologne that led to the founding of the gallery, the landmark exhibition THE KÖLN SHOW, the beginnings of the digital revolution and the radical reformulation of the notion of the exhibition in the 1990s.

|

|

|

Brigitte Jacobs van Renswoun (BJvR) How did you come to Cologne, and how did the Cologne art scene appear to you at the time?

Esther Schipper (ES) Cologne was a place where you could encounter and experience recent art history as it was emerging. I had just finished school in Paris and moved to Cologne after I had seen how exciting the city was during a visit, including a Christmas party at the studio of the Mülheimer Freiheit. After some time I met Monika Sprüth, who had just opened her gallery. I was her first assistant, that was in 1983/84, and later I started publishing multiples: The first one, the Balaklava Wool Edition, I produced with Rosemarie Trockel in 1986.

In 1987/88 I left Cologne for a year to complete a curatorial curriculum at MAGASIN in Grenoble. It was the first year of the program and comparable to the Whitney's Independent Study Program in New York. In Grenoble I met Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Philippe Parreno, who were studying at the Academy of Arts. But Gonzalez-Foerster also took part in the MAGASIN program. A selected group of well-known people from the art world, such as Kasper König and Nicolas Serota, were actively involved. This is how it came about that I did an internship with Serota at the Whitechapel Gallery in London during my studies. In London I met Angela Bulloch and Liam Gillick. These artists – Angela, Dominique, Philippe and Liam – formed the core of my work as a gallery owner and still play a key role as artists in my gallery today.

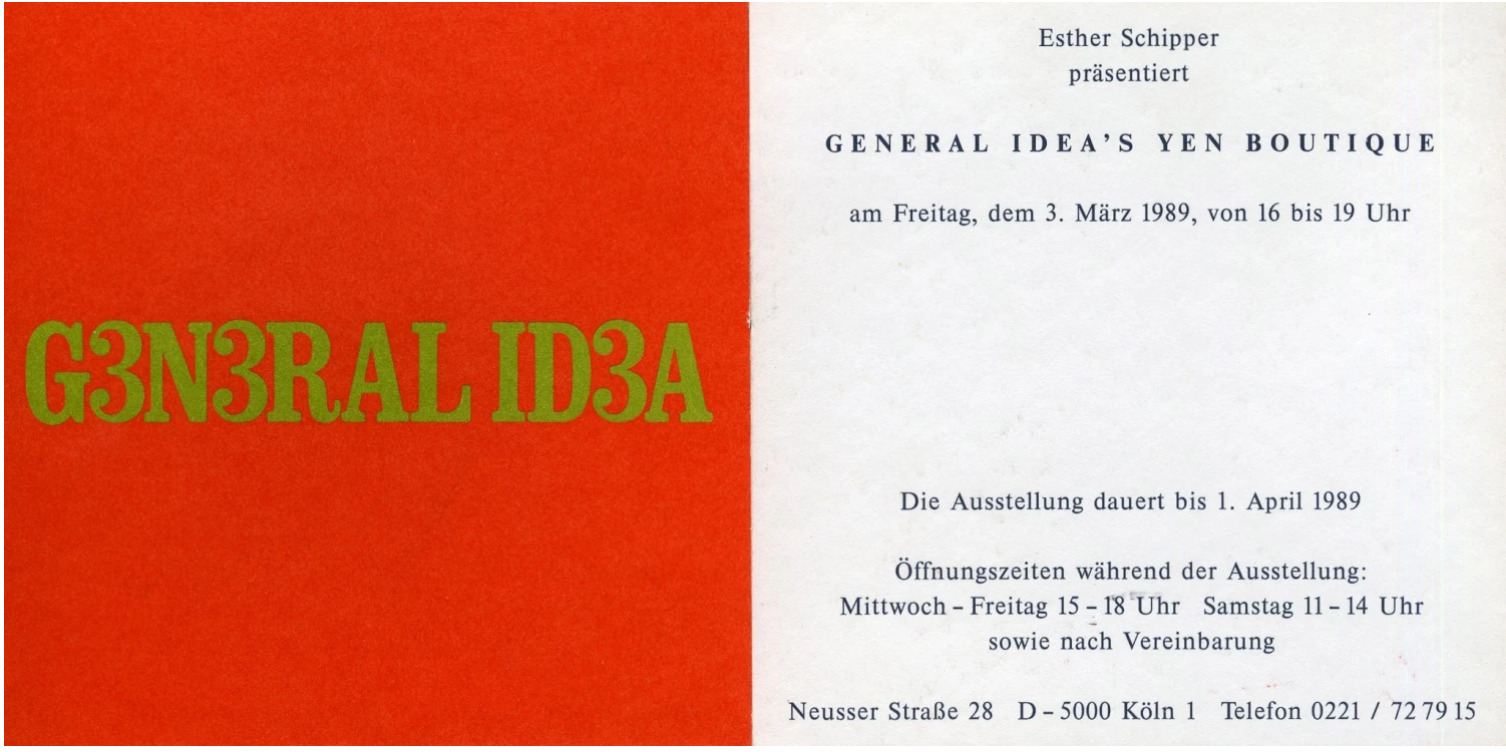

BJvR In 1989 you founded your own gallery ...

ES I founded the gallery in 1989 and opened, as mentioned, with the General Idea’s ¥en Boutique. I have been working with many of the artists, including Angela Bulloch, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Liam Gillick, Philippe Parreno, who radically rethought the format of the exhibition and used it as a critical medium, since the 1990s. To this day, the gallery represents AA Bronson and the Estate of General Idea.

In 1990, together with Daniel Buchholz, I then opened a room with multiples, editions and books in Albertusstrasse. What was interesting at that time was the way the galleries cooperated: We worked together and with the artists to make experiments possible. One project, for example, was at the 1990 ART COLOGNE: Daniel Buchholz and I installed identical booths. Julia Scher, who exhibited in the gallery for the first time the following year, connected the two booths with a live CCTV circuit – at that time, this was still technically quite complicated.

|

|

|

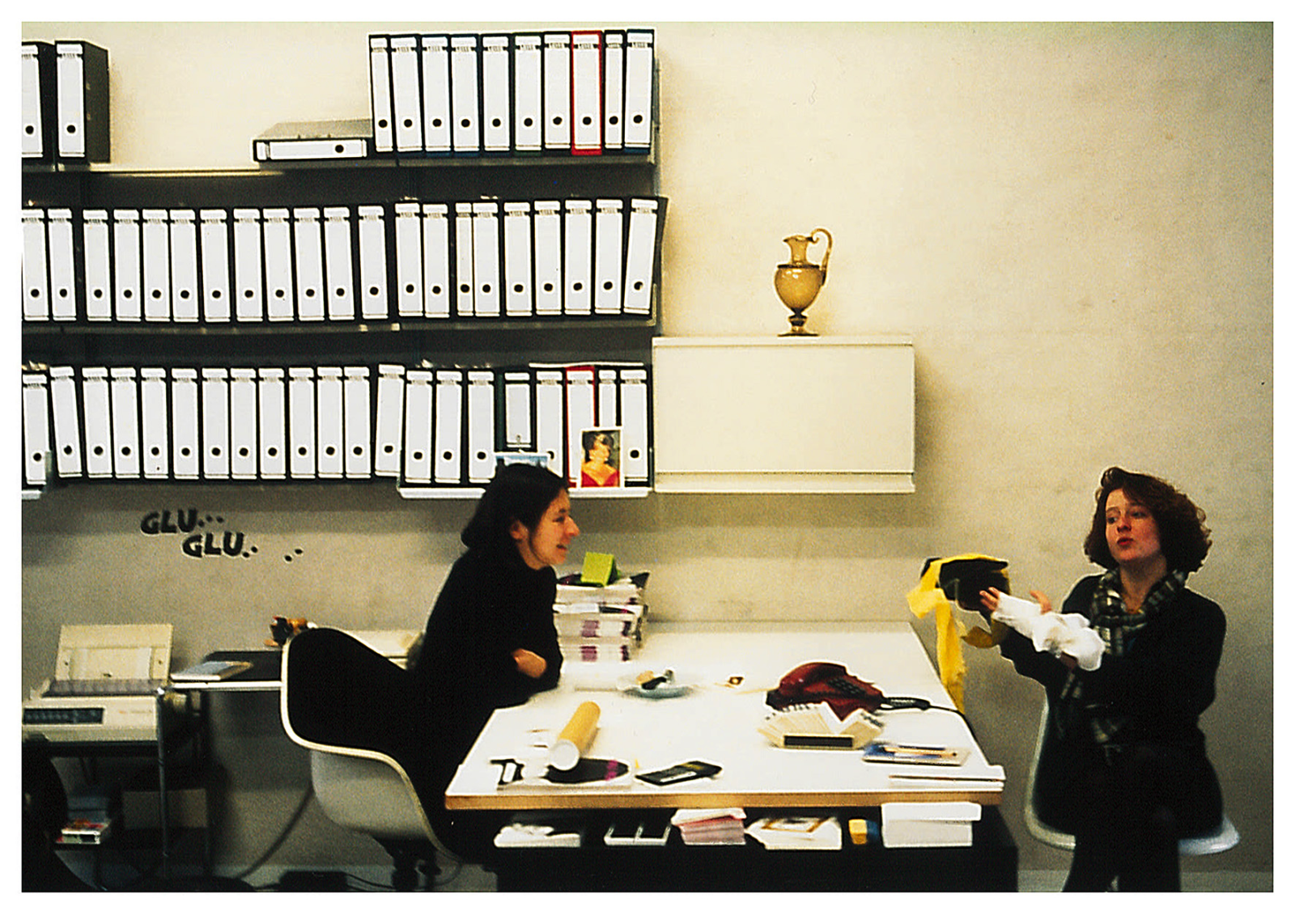

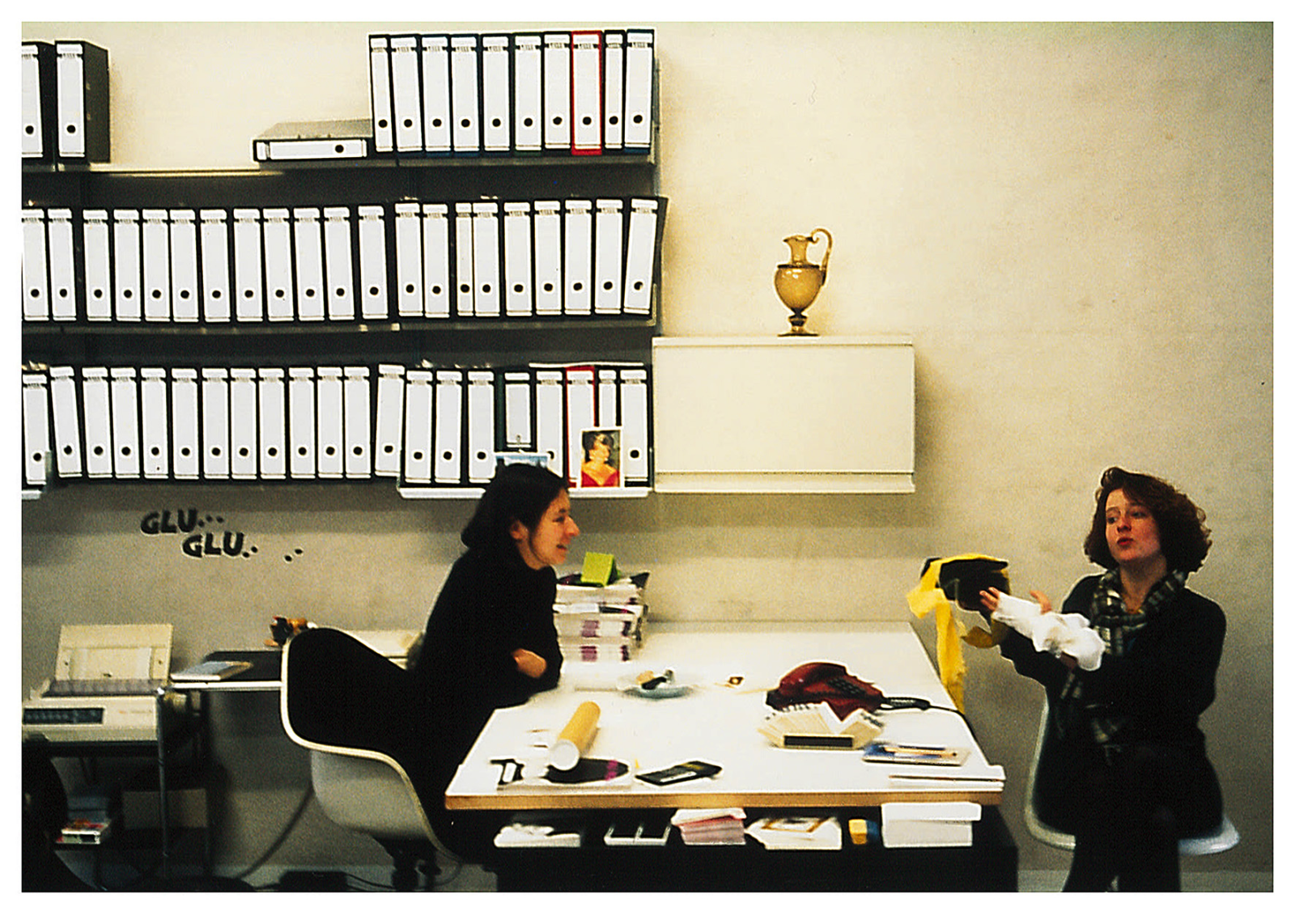

| Esther Schipper with Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster in the 1990s in Cologne.

| |

|

BJvR Was the idea of a joint exhibition also a new approach, in the sense of a different collaboration among galleries, like the formation of networks or corporations?

ES The time was marked by experiments. The difference between galleries that operated more along the lines of the traditional art dealer model and the new spaces that I and artists of my generation wanted to work in was enormous. I wanted to create exhibition spaces, but also a discursive space in which the changes in the concept of art and exhibition could be addressed. The approaches of my first exhibition projects – such as General Idea's ¥en Boutique or, in November of the same year, Readymades Belong to Everyone®, an agency founded by Philippe Thomas to address the characteristics of the art market – were decisive for me: the concept of art was to be expanded, the traditional boundaries of medium-specificity were to be dissolved. Ultimately, everything could be art: every medium, the relationships that developed in exhibitions, the role of the viewer, or even the preoccupations and ideas of the artists themselves. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster thematized her experiences and memories when she began the Chambres series, Angela Bulloch chose rules from institutions, organizations, or even from a New York strip club like the Baby Doll Lounge and made them into her Rules (whose form as a work of art is completely variable: The owner gets an A4 sheet of paper, but can also fill a wall with it), and Liam Gillick, with McNamara, exhibited elements of a non-existent film that put the American Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, John F. Kennedy and a series of partly fictional characters in dialogue. For me these approaches were very important – and are still relevant. I also associate with this time the idea of using the gallery as a laboratory. One such laboratory project, for example, was 240 Minutes by Lothar Hempel and Georg Graw. The title-giving 240-minute video compilation (with contributions by Angela Bulloch, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Wendy Jacob, Liam Gillick, Pierre Joseph, Lothar Hempel, Philippe Parreno, and Julia Scher, among others) was produced entirely in the gallery: The production dates were announced in advance and visitors were able to watch the filming, as well as the editorial documents and meetings of the team. The transparency of the production process was incredibly important for this project. Equally crucial was the open, if you will, non-hierarchical approach to the various media. In the early 1990s, a market for video or film work was still largely unimaginable, not to mention performance. But the groundwork was laid during this time, so that today it no longer seems unusual for an institution like the MoMA to have a film by Philippe Parreno, a sculpture with live bees by Pierre Huyghe, or a situation by Tino Sehgal in its collection – and private collectors are no longer afraid to buy conceptual, ephemeral or performative works. This was quite different in the 1990s: as a gallerist, you had to do a lot of persuading, have many conversations, without playing down the complexity of the works and their radicality. ...(The pdf of the full interview is available on our website, both in German and in English.) |

|

|

Online Viewing Room - Thirty Years / Angela Bulloch coming soon!

|

|

Angela Bulloch has been with the gallery from the very beginning. The artist has had eleven solo exhibitions and her work has been included in countless of the gallery’s group presentations. We celebrate the thirty-year anniversary of her first solo exhibition with Esther Schipper with an Online Viewing Room which will include historical documentation, information on all her major bodies of works and video content. Online next week!

|

|

|

| A selection of exhibition views spanning 1990 to 2014.

| |

|

Zapp Magazine Collaboration: Streaming historical footage

|

|

We are happy to inaugurate a collaboration with Zapp Magazine, a pioneering international art magazine onvideo produced between 1994 and 2007. Every issue of their ‘videozine’ offered around 90 minutes of visual material presented on a VHS tape. In recent years Zapp Productions has digitalized its videos and is making it available on DVD. Active predominantly in the mid to late 1990s, Zapp Magazine released eleven tapes during this period, each issue a compilation of footage from exhibitions, performances, artists' videos, interviews, and openings. In the coming weeks we will feature a wide range of materials: documentation of groundbreaking group exhibitions such as the 1996 Traffic at the CAPC Musee d’Art Contemporain in Bordeaux, solo exhibitions of gallery artists and footage from openings in our Cologne space. We begin with Julia Scher’s lecture/performance Safe & Secure with Julia, presented in 1994 on occasion of her solo exhibition Don’t Worry at the Kölnischer Kunstverein in Cologne. Originally included in Zapp Magazine Issue # 3 October 1994. WATCH THE VIDEO HERE

|

|

|

The Reading Corner: Documenting Art Exhibitions

|

|

The documentation of art exhibitions is also a subject of Cristina Garrido’s 2019 project entitled The (Invisible) Art of Documenting Art. Garrido investigated the role of photographers, in particular the paradoxical tension between the growing demand for their images and the discreet recognition these professionals often have in the art system. One of the eight photographers she spoke to was Andrea Rossetti. The book that resulted from her project features a selection of his photography and an extensive interview with Andrea. READ PAGES FROM THE BOOK HERE

|

|

|

The Reading Corner: OneStar

|

|

In a generous gesture of bringing art into life, OneStar has made available pdfs of all their artists’ books published since 2000. We salute them! DOWNLOAD THE BOOKS FOR FREE HERE

|

|

|

Under the heading Messages from Home artists are sharing videos from their (temporary) studios or homes.

This week Isa Melsheimer takes her plants out for some fresh air on the roof.

|

|

|

| Karin Sander, Oyster Mushroom / Austernpilz, 2012, Oyster Mushroom, stainless steel nail, dimensions variable. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020. Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

“While I was studying art history, the masterfulness of still life painting always fascinated me. Although this genre was considered the lowest in the tradition of painting, the hyper realistic fruits, moist and firm, almost bursting of mellowness, felt to me like an incredibly sophisticated challenge for artists to achieve. Even the Greek allegory of Zeuxis and Parrhasius encounters the deception of reality with their famous ‘painting duel’, attempting to find out who’s able to paint as close to life as possible. Karin Sander deals with that traditional quest in her very own and radically conceptual way.

Her ‘Kitchen Pieces’ are fruits or vegetables fixed to the wall with a nail, in this example the work consists of an oyster mushroom. The sculpture is a temporary piece that can be repeated as wished, therefore shows a straightforward mortality by displaying the spoilage of the fruit or vegetable in a gallery space. Some might want to exchange the mushroom every day, to keep its condition splendid and in perfect shape, but some might also want to explore what’s left of it after several weeks or months."

– Jonas Kriszeleit |

|

|

A paintbrush, a camera, a robot, disregarded doorstops or even an Ouija board – how much can you tell of an artist by what’s in their studio? SEE INSIDE THE STUDIO HERE

|

|

|

|

|