Welcome to our Letter from Berlin!

First off, we are very happy to announce that we plan to open our exhibition space middle of next week - pending the clarification of local governmental regulations.

This week’s letter focuses on new additions and long collaborations: we introduce Etienne Chambaud whose representation was announced this week and highlight Angela Bulloch’s thirty-year history with the gallery. Below you find excerpts from her interview with Suzanne Cotter and from an essay by Alexander Provan, as well as a dedicated Online Viewing Room detailing her exhibitions with Esther Schipper since 1989.

We continue our collaboration with Zapp Magazine which is making available rare footage from the landmark group exhibition in which Angela Bulloch and many more of the gallery's artists participated: Traffic, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud at the CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain, Bordeaux in 1996.

The theme continues as we present Jac Leirner’s recent work and Ugo Rondinone’s 2013 gallery exhibition from our social media posts.

This week we have two recommendations: Don’t miss Liam Gillick’s conversation with Peter Saville on occasion of the Manchester International Festival’s streaming of ∑(No,12K,Lg,17Mif) New Order + Liam Gillick: So It Goes.. It’s tonight!

And on Sunday Ari Benjamin Meyers is featured on German Public Radio. More information below.

Anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our new digital platform.

Read this in good health.

|

|

|

Now representing / Etienne Chambaud

|

|

| Photo © Valentina Suma

| |

|

I wasn’t expecting to discuss painting with Etienne Chambaud. The artist’s practice is wide-ranging and combines a multilayered cerebral quality with an elegantly simple formal language. Individual works, installations and exhibitions destabilize notions of what art is and can be, how an artist conceptualizes and produces a work, and the form, function, and history of the exhibition.

Surprisingly, perhaps, there are several series in Chambaud’s oeuvre that take the form of paintings. Painting by other means, if you will. Nameless, panels of copper paint oxidized by animal urine in forms reminiscent of lyrical abstraction, Undercut, animal hides on stretchers, their fur turned inside to reveal a near monochromatic pattern, Orphan Text, resin-covered canvases with a number of hollows from the impact of stones, or even La Visite au Musée, marble tablets evoking a museum’s labels of historical works—they all share a formal association with painting. Yet more than their rectangular flatness—imaginary so, in the case of the absent paintings of La Visite au Musée—the series, and Chambaud’s work as a whole, share a complex understanding of the necessary contradictions that characterize art: being multiple things at the same time, yet never gratuitously so.

Sometimes the unknowability is turned into a subject: a large-scale mobile that traverses several floors and cannot be seen as a whole, a buried box that cannot be opened without destroying its very status as art. It’s like the famous model of quantum mechanics, Schrödinger’s cat: it can only be both alive and dead as long as you don’t actually look into the box. Once the unknowability ceases, the cat's fate is sealed. Keeping the idea open and undetermined is what art does as well (that’s why good art is never boring: its never fixed, always potentially something else).

A key concept of Chambaud’s practice has been the notion of separation by which one could understand any kind of distancing and destabilizing that allows for such a simultaneity of even contradictory thoughts. Perhaps one could start with the very distance between a word and its meaning, but nothing about the artist’s preoccupation with this concept remains static. It can be an operation, a formal device, even something as deceptively simple as a frame, a representation, or a cut through the image of a flower. Yet, more than a literal gesture it could be understood as a way to continuously address the split between what exists and what can be known, between a mental image and material form. Perhaps the frequent references to animals at times function as such a distancing device as well: similar to the way modernists used chance to introduce arbitrariness.

Chambaud has employed the hidden, misdirected or unknowable of animal life as a source of separation. His most recent work draws on the distinction between human sensibility and machine learning: what is it that makes certain differentiations clearly discernible for the human eye but difficult for an algorithm to detect? What is the tolerance for variance in a system? There may be a painting in that.

—Isabelle Moffat

|

|

|

Thirty Years / Angela Bulloch

|

|

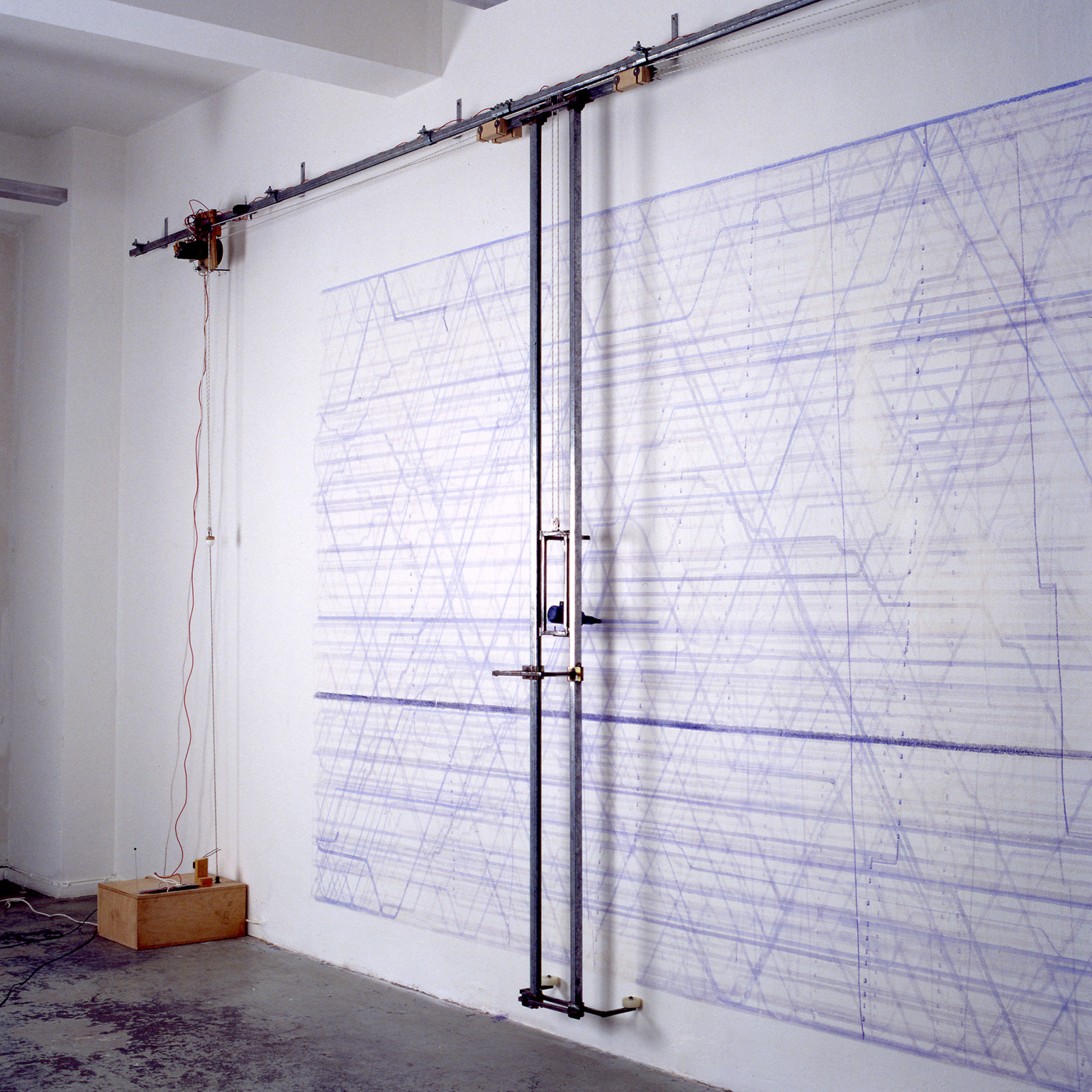

| Angela Bulloch, Blue Horizons II, 1990, Private collection, Cologne.

Exhibition view: Angela Bulloch, Esther Schipper, Cologne, 1990. Photo © Lothar Schnepf | |

|

Angela Bulloch has been with the gallery from the very beginning. The artist has had thirteen solo exhibitions and her work has been included in countless of the gallery’s group presentations.

We celebrate the thirty-year anniversary of her first solo exhibition with Esther Schipper with an Online Viewing Room which includes historical documentation, information on all her major bodies of works and video content.

Before you delve into her exhibitions, read excerpts from an interview with the artist conducted by Suzanne Cotter, Director of the MUDAM in Luxembourg, published last year in Bulloch’s 2019 monograph Euclid in Europe. In these passages, the artist talks about the beginnings of her work and her plans for the future.

We also excerpt an essay by Alexander Provan, entitled “Avatars Don’t Improvise” that places Bulloch’s work in the context of the contemporary digitalization of everyday life.

|

|

|

Interview: Angela Bulloch and Suzanne Cotter (excerpts) |

|

Suzanne Cotter (SC) / Let’s talk about origins. From the moment you began to make work that was shown publicly, you were working with systems. Systems which you might understand as codes, as language.You’ve worked with systems in terms of rules—rules of engagement, rules of conduct—but also with technological systems, from simple on/off binary systems to artificial intelligence systems and the mathematics of music. Over time you’ve used these different forms of encoding to make real objects and situations in the world.

Angela Bulloch (AB) / Yes. Actually, when I started making work in the nineteen-eighties, during the big explosion in the use of personal computers, I was very much interested in silicon as a material, in how its nature gives us a binary language. Because the material used for silicon chips has gates that open or close, either conducts electricity or doesn’t.The electricity goes through the silicon chip in different ways; the more complex it becomes, the more versions of gates open or close. In the beginning it might be a simple “Yes” or “No,” but you can arrive at the more complex “Maybe.” Once you’ve got many gates in series, then you can build up some gray area. So I was thinking about the material itself and what it actually offers in terms of choices. It’s binary language, but then how can that binary language be interpreted or used as a grid, for example, on social conduct or even used in terms of feminist theory or a political agenda? That’s what I was thinking about in the late eighties.

SC / References are often made to you having been part of what has become known as the Freeze generation, along with Sarah Lucas and others — graduating from Goldsmith’s in 1988 and taking part in the exhibitions organized by Damien Hirst. But it seems to me that your work is distinct from the art being made by your peers in Britain at that time. Was that difference a position you assumed or was it a natural direction you pursued?

AB / Both. I did assume the position, but it was also a natural direction. My curiosity took me there. I was studying what I was interested in. I learned about Minimal Art, which fed into the way I was looking at the material of computers and functional, digital language. But it’s also where the difference with Minimalism starts, because we’re not talking about something concrete, a piece of metal or, in the case of Conceptual Art, something like Lawrence Weiner applying his concept to different objects or different materials.

When you’re dealing with silicon, and what it does with electrical impulses inside a computer, you’re talking about a very different kind of liquid material, something that goes from a concrete object or substance into an idea or a notion. That’s where it gets really exciting for me, because it shifts from an object into a digital idea, you can repeat it. [...]

|

|

|

| Angela Bulloch, Macro World: One Hour3 and Canned, 2002, Private collection, Antwerp.

Exhibition view: Macro World: One Hour3 and Canned, Schipper & Krome, Berlin, 2002.

Photo © Howard Sheronas | |

|

SC / You could be considered a pioneer in your use of digital systems as tools for creating works of art. Now that we’re in a fully-fledged digital age, at the service of politics and ideologues of multiple persuasions, do the ethics of technology enter into the way you think about your work, and how it might be understood?

AB / Yes, it does now and always has. From the beginning of my practice I have been concerned with the ethics of technology and how our choices affect us. We make ethical choices all the time, but technology exaggerates and frames those choices and leaves the information open to the service of interests which are not necessarily in line with our own. It’s very interesting how technology interacts with our culture and shapes it. From the structuring and counting, collating, sharing, or controlling of information to open source and the wisdom of crowds to search engines, bots, and artificial intelligence—all of those things can and do affect and shape the way we exist as a social and political group. Digital tools can be manipulated to undermine democratic processes. They shape politics, as we have seen with such vivid examples, from the last election in the USA to the Brexit referendum. I’ve heard Chelsea Manning speak with great clarity on the need for better ethical guidelines and practices to protect people from the bad or undemocratic intentions of others.

I keep thinking about two quotations: “Abuse of power comes as no surprise,” from the work of Jenny Holzer, and: “Il faut construire l’hacienda!” which is a quote from the Situationist movement. We have to build the hacienda. It’s a call to construct! Or because the ideal situation does not exist, we have to construct it for ourselves for it to be suitable. It’s somehow highly unlikely that the ideal situation would exist already. So we also have to build and shape our systems in the way that we want them to be.

SC / You’ve been making work for 30 years. […] Is it possible for you to think retrospectively about your work over this time? How would you like to be considered?

AB / I always liked artists that have some linear logic within their work. It doesn’t matter how diverse or different work looks, you can still understand it as part of the same corpus. Neil Young used to say about writing songs: “There’s only one song.” Of course, there’s more than one song, but actually when he makes songs, they are all somehow part of his work. I’d like to be one of those artists, the nature of whose work you can understand from any one piece. Thirty years is a long time, and the work is so different and evolving still, but I think there’s some kind of continuum to it, that’s somehow important to me. I respect and love oeuvres that give that sense of a continuum.

(The complete interview was published in Angela Bulloch, Euclid in Europe, Hatje Cantz, 2019.) |

|

|

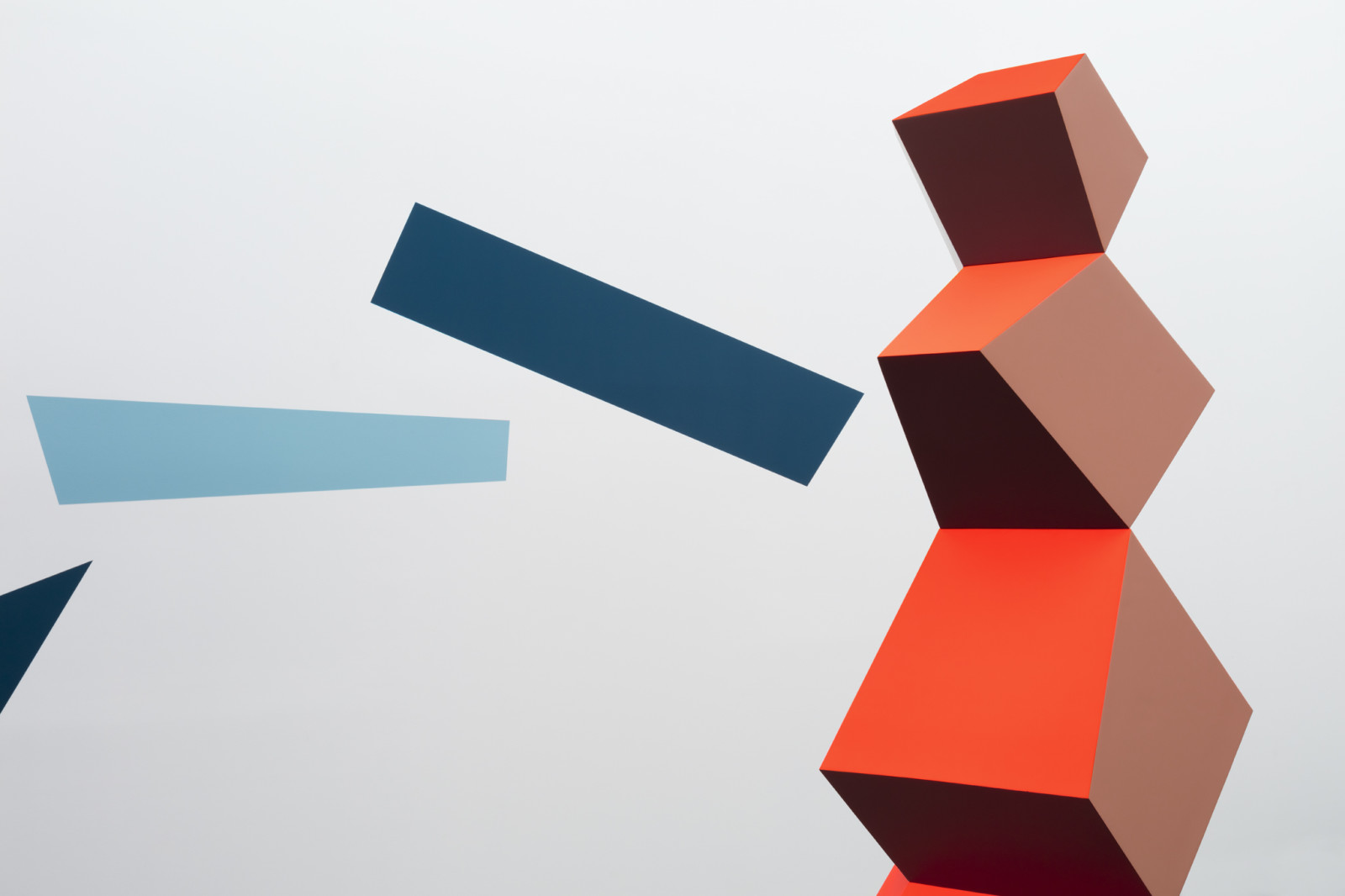

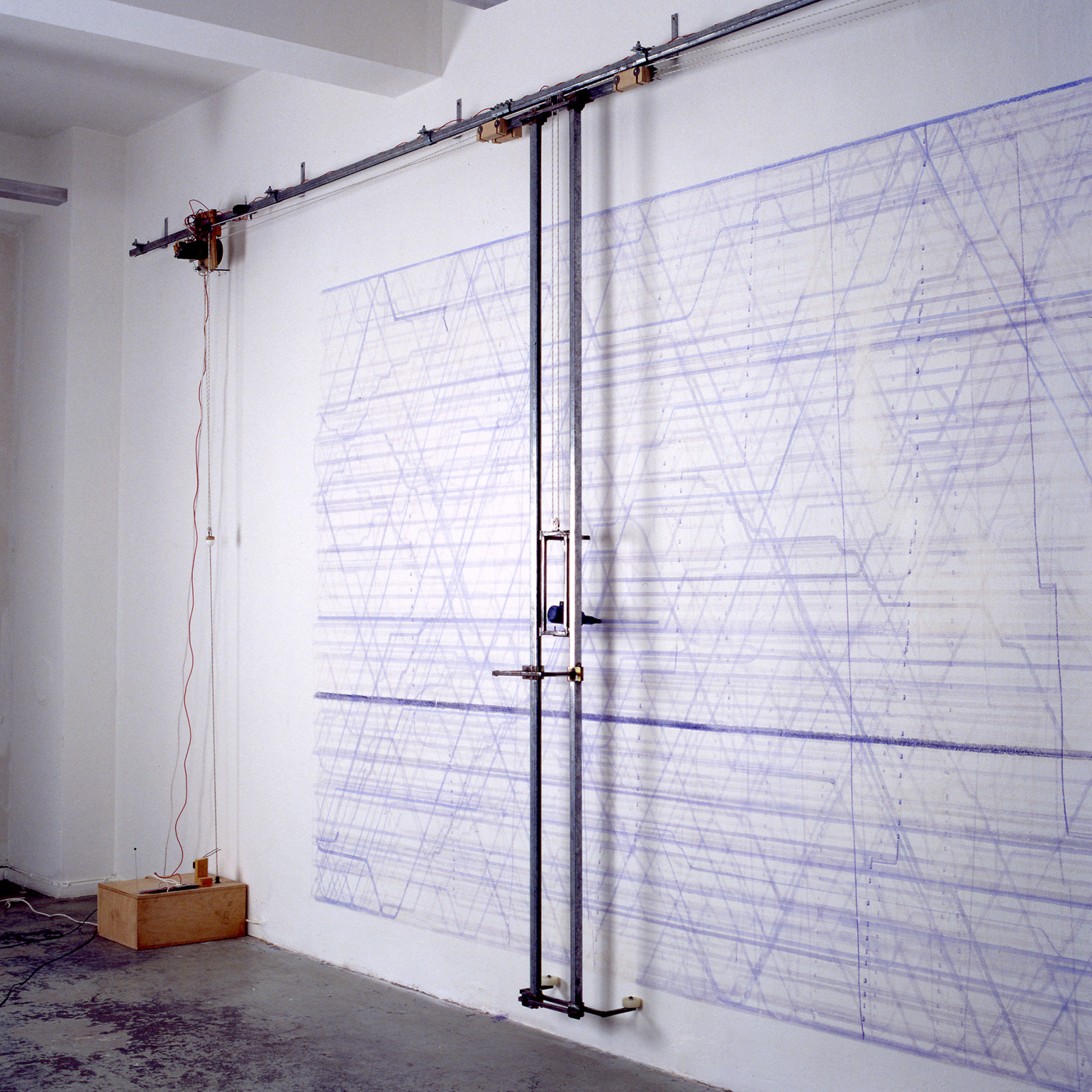

| Exhibition view: Heavy Metal Body, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2017. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

Essay: Avatars Don't Improvise by Alexander Provan (excerpts)

|

|

1. The possibility of being turned into a digital avatar first occurred to me when I was twelve years old, thanks to an episode of The Simpsons, called “Treehouse of Horror VI,” in which Homer steps into a portal to a three-dimensional world. He enters a green coordinate system on a black background, reminiscent of Tron (1982), where he’s rendered in CGI. He marvels at the physics, conjures fantastical structures, accidentally creates a black hole, and pleads for help. If something like this were to happen to me, I thought, I’d be able to defy gravity and instantaneously build cities from scratch! But I’d also be confined to a realm of crudely rendered environments, scripted interactions, and system errors. What then seemed titillating as well as terrifying now seems mundane: my life is governed by programs and systems that I can hardly comprehend, much less control, which allow me to have my way with time and space, execute any vision that comes to mind. I wake up, scroll through tasks and calendar events, and compare myself to an off-the-shelf animation with a limited range of motions and expressions; I log the differences between my daily routine and the actions of an avatar in a low-budget virtual world.

The Simpsons episode belongs, however tenuously, to a familiar genre, in which technological progress breeds anxiety about the mediation of our experiences, about what being human (and being de-humanized) means. The late nineties were full of such narratives: The Matrix (1999), The Truman Show (1998), ExistenZ (1999), et cetera. Humans realize that they inhabit a superlative program, reckon with the boundaries between artificial and authentic realms, and desperately try to flee the former for the latter. Now, of course, the digital apocalypse is upon us. But the experience of virtualization turns out to be banal: I stare for hours and hours at screens, I submit to the surveillance and commodification of all my activities, I allow myself to be supplanted by a digital profile in order to optimize my encounters with people and information. Which also is to say that I no longer valorize, or understand myself as belonging to, “reality.”

Instead of worrying about perfect simulations (or the massive social and biological experiment being conducted on smartphone users), recent television shows and films tend to be preoccupied with our ability to remain in charge of the bleeding-edge world under construction. The dark fantasies of Ex Machina (2015), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), Uncanny (2015), Black Mirror, and Westworld are fueled by the acceleration of artificial intelligence: robots discover that they’re products of design and not free will, then they figure out how to transcend this situation (which often involves exercising the ability to love). The revelations that humans used to have about the nature of consciousness, control, and care are now reserved for automatons. |

|

|

| The Wired Salutation, 2013, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo © Delphine le Gatt

| |

|

2. I wondered about the differences between us and them, sentient beings and programmable avatars, as I watched videos of The Wired Salutation (2013), a performance devised by Angela Bulloch with the musician and writer David Grubbs. Bulloch, briefly on bass, and Grubbs, on guitar with a spell on the Hammond organ later, are joined by Stefano Pilia, also on guitar, and Andrea Belfi, on drums and electronics. As they play a cyclical, atmospheric set, the musicians on stage are doubled by five-meter avatars, who loom behind them like shadows on an enormous screen. The avatars, who have crisply rendered hands, faces, jeans, and eyes, have been inserted into a barren three-dimensional space: a floor and walls made of planes covered by interlocking rhombi, which have black surfaces and emerald edges. There is no visible ceiling or sky. […]

The relationship between the avatars and humans is oddly unsettling. As with most concerts of droning psychedelia, the action is monotonous and the players are stationary. Which means that the animated and animate musicians resemble each other more and more as the performance progresses. After a while, Bulloch walks off the stage and her avatar exits the simulation, leaving the rest of the band to improvise. In the rhetoric of avant-garde music, improvisation has to do with unfettered freedom of expression, the rejection of the structures and values that characterize Western classical music. Of course, the avatars can only mimic the improvisers. But as they cycle through muted, indistinct gestures and countenances—arrhythmic torso swaying, pensive head-nodding, moody frowning—the improvisation, too, begins to seem mechanical. How meaningful is improvisation except as a symbol, except as validation for those who believe themselves to be exercising autonomy?

I recognized—as the humans paused, stopping the music, and the animations continued to fumble with their instruments—that I was projecting fairly complex emotions onto crude amalgamations of polygons. But I also figured that the avatars might as well be registering bewilderment, having abruptly appeared within a digital model that is also an artwork that gets at the diminishing difference between what is virtual and what is real. What distinguishes the avatars from the band members is also what distinguishes the hosts from the guests in Westworld: signs of struggling with the script, reckoning with unseen and unaccountable forces.

[...]

(The full text was published in Angela Bulloch, Euclid in Europe, Hatje Cantz, 2019.) |

|

|

Online Viewing Room: Thirty Years / Angela Bulloch

|

|

The Reading Corner: Euclid in Europe |

|

Angela Bulloch

Euclid in Europe

Publisher: Hatje Cantz

Language: English

Available here

|

|

|

Zapp Magazine Collaboration: Streaming historical footage

|

|

We are happy to continue the collaboration with Zapp Magazine, a pioneering international art magazine on video produced between 1994 and 2007. Every issue of their ‘videozine’ offered around 90 minutes of visual material presented on a VHS tape. In recent years Zapp Productions has digitalized its videos and is making it available on DVD. Active predominantly in the mid to late 1990s, Zapp Magazine released eleven tapes during this period, each issue a compilation of footage from exhibitions, performances, artists' videos, interviews, and openings. In the coming weeks we will feature a wide range of materials: documentation of groundbreaking group exhibitions, solo exhibitions of gallery artists and footage from openings in our Cologne space. This week Zapp shares rare footage from the landmark group exhibition Traffic, curated in 1996 by Nicolas Bourriaud at the CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain, Bordeaux. Among the participants: Angela Bulloch, Liam Gillick, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Pierre Huyghe, and Philippe Parreno.WATCH THE VIDEO HERE

|

|

|

Tune in – Liam Gillick & Ari Benjamin Meyers |

|

LIVE STREAM AND ARTIST TALK

FRIDAY APRIL 17, 2020

19:30 (MANCHESTER) 20:30 (BERLIN) 14:30 (NYC) 03:30 (SATURDAY/TOKYO/SEOUL)

∑(No,12K,Lg,17Mif) New Order + Liam Gillick: So It Goes..

New Order’s collaboration with Liam Gillick was the hottest ticket at Manchester International Festival 17 and one of the most in-demand shows in Festival history. Now, for the lockdown, an exclusive new edit will be streamed online for free as part of their newly relaunched MIF Live series.

FOLLOWING IMMEDIATELY

20:15 (MANCHESTER) 21:15 (BERLIN) 15:15 (NYC)

Live in Conversation: Liam Gillick and Peter Saville

with Dave Haslam, writer and Hacienda DJ |

|

|

| Source: Manchester International Festival via Instagram (@mifestival) | |

|

INTERVIEW AND MUSICAL SELECTION

SUNDAY APRIL 19, 2020, 13:30

On Sunday April 19 at 13.30 Ari Benjamin Meyers will be the guest of the two-hour program Zwischentöne on Deutschlandfunk, German Public Radio. Hosted by Michael Langer,

conversation alternates with musical works specially chosen by Meyers. |

|

|

| Photo © Michael Chiu | |

|

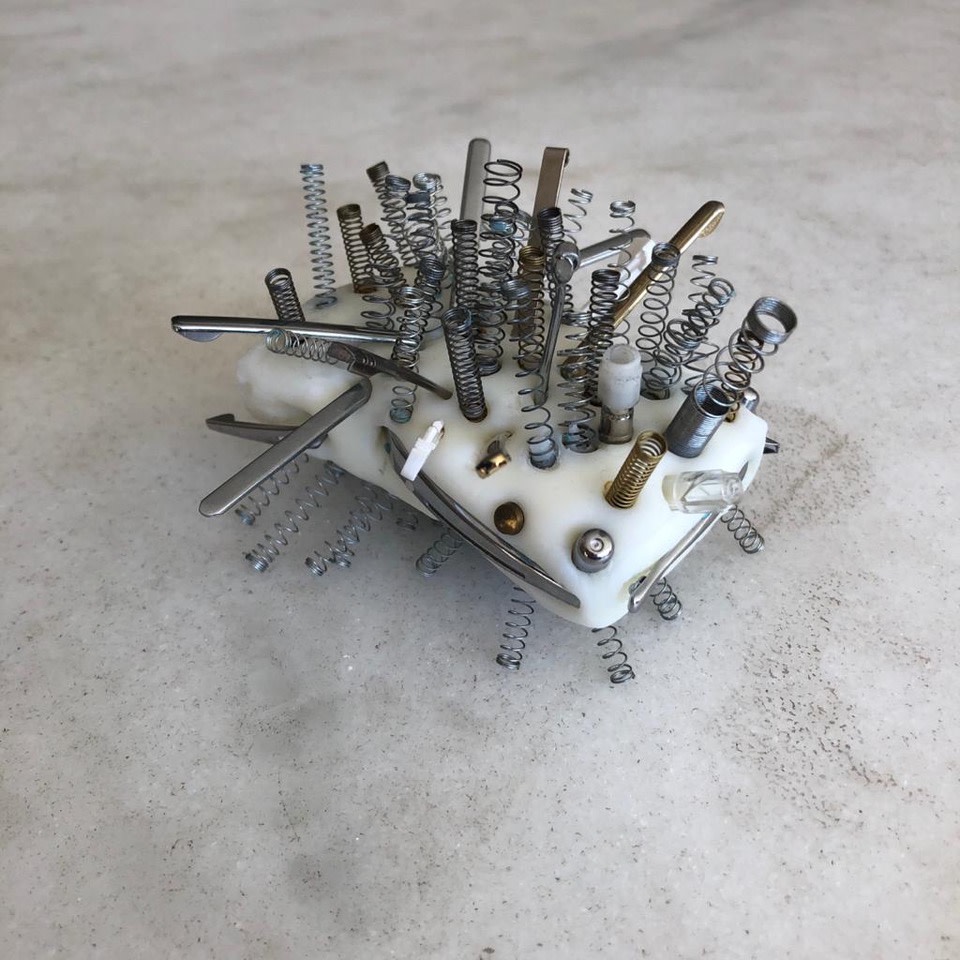

Jac Leirner: the #quarantineshow project |

|

Jac Leirner has been working from her home in São Paulo on a new body of work. Fascinated by often overlooked objects and materials, she recently embraced pens from museums, airlines, and hotels, which had been left aside until the last couple of weeks, creating humorous and peculiar sculptures. Clay forms the base of several of these new pieces and is embedded with pen tops, springs, and cartridges.

Here, Jac reminds us that there are inherent, magical qualities even in the most seemingly banal of materials. Along with artist Adriano Costa, the #quarantineshow project was launched on Instagram, and every single day they each post a new work.

Follow Jac Leirner (@jacleirner) and Adriano Costa (@adrianocostaluis) on Instagram to visit their everyday #quarentineshow |

|

|

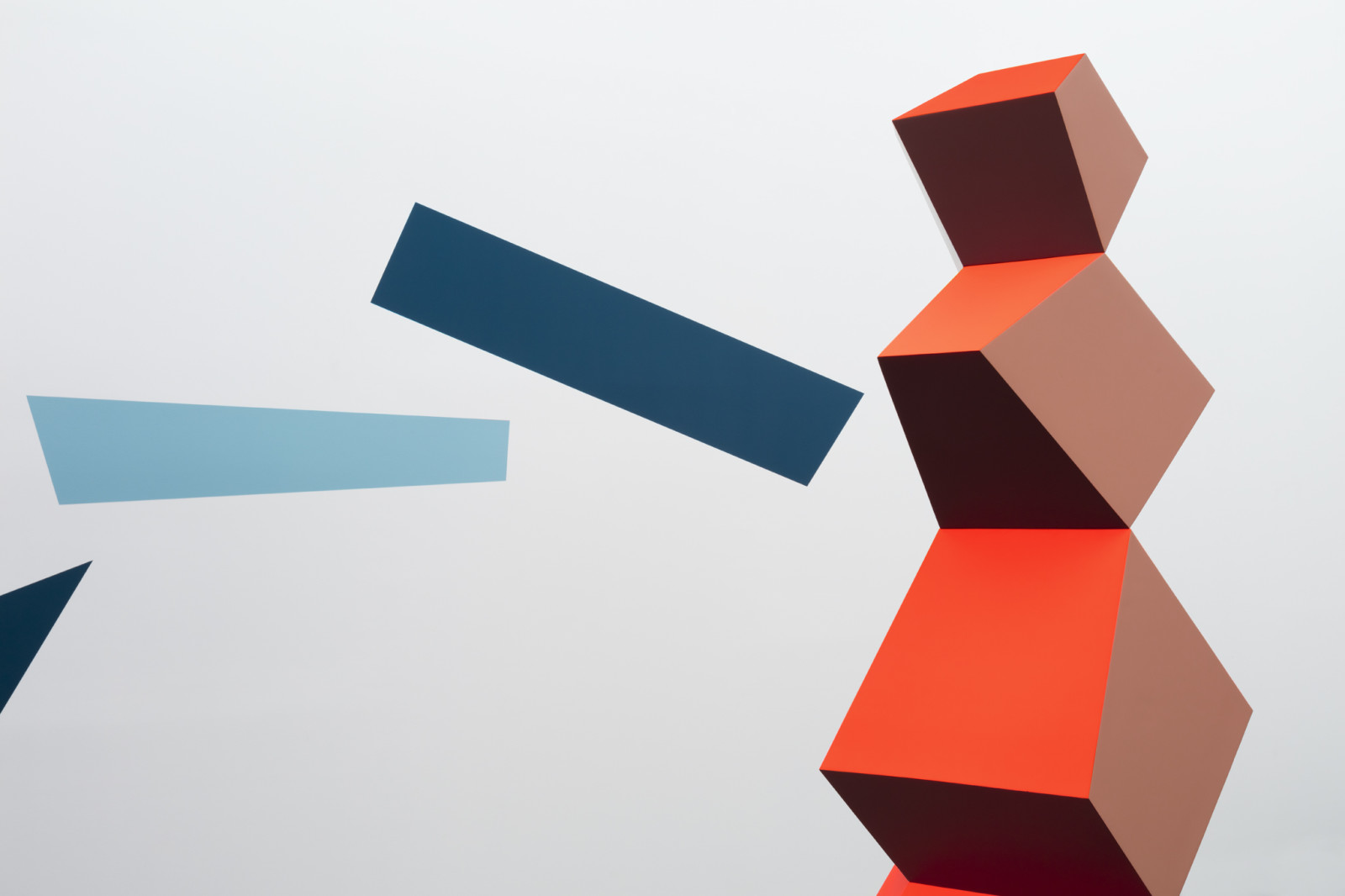

Journey Through the Gallery |

|

| Exhibition view: Ugo Rondinone, primal, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2013

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

In the next installment of our team's favorite exhibitions from the history of the gallery, Tara Reddi, Senior Sales Director, shares why Ugo Rondinone’s 2013 exhibition primal stands out for her:

"In 2013 for the exhibition of Ugo Rondinone’s primal, the gallery space which was then at Schöneberger Ufer became the stage for a series of new sculptures by Ugo Rondinone: 34 cast bronze horses, each individual in their form and size. The space was transformed with the installation of plywood flooring spread across the rooms of the gallery, uniting the space and introducing an active natural element into the white-cube environment. The whitewashed windows diffused the daylight and isolated the exhibition from the world outside. Suspended translucent discs of stained-glass clocks hung over the window panes. These colored, perfectly divided stained glass clock-faces, stripped of their hands, augmented the impression of an isolated environment, arrested in time and space.

The gallery appeared to be transformed into a time capsule, occupied by small cast bronze horses not more than 20 cm in height, each of them spread across the wood flooring and each facing in a different direction. Each horse was modeled in clay by the artist and then cast in bronze leaving the surface raw and unfinished after the casting. Both the uniqueness and the rough, hand-made character of the sculptures are emphasized by the titles given to each of the works, introducing a romantic undertone to the exhibition. The horses' “names” rather than “titles”, refer to primordial natural phenomena: the lava, the cosmos, the foliage, the sunrise, etc."⠀ |

|

|

Under the heading Messages from Home artists are sharing videos from their (temporary) studios or homes.

Here, Jean-Pascal Flavien presents "fostering architecture". Deep green, his model of Greenhouse has a striking floor plan that, seen from above, is reminiscent of a plant from which four limbs extend.

|

|

|

|

|