Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Fassung des Briefes aus Berlin

Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! In anticipation of our upcoming exhibition with Jac Leirner, we look at her body of work made from vintage plastic bags begun in 1985. ARCOmadrid is in full swing and remains open through Sunday. We highlight Daniel Steegmann Mangrané's new series of holograms, as well as works by General Idea and AA Bronson in the fair's Anniversary section. Different notions of history are addressed in Christoph Keller's video work Anarcheology from 2014. And don't miss Thomas Demand's exhibition at the Centro Botín. We reprint a short interview in which Demand speaks about the exhibition architecture and introduce the accompanying pop-up book and Centro Botín's virtual site. Hito Steyerl was profiled in the New Yorker. Andrew Grassie and Rodney Graham participate in an exhibition on the artist studio at London's Whitechapel Gallery, to rave reviews. Simon Fujiwara's exhibition Once Upon a Who? is closing this Saturday while the artist's 2011 work entitled Letters from Mexico is now on view at the Hamburger Kunsthalle. And finally, the Reading Corner returns with a selection of books. We hope you enjoy our Letter from Berlin!

|

|

|

Opening Soon – Jac Leirner at Esther Schipper |

|

| Jac Leirner, Us Horizon, 1985–2022 (detail). Photo: Edouard Fraipont | |

|

We are delighted to announce a solo exhibition by Jac Leirner.

Opening Saturday March 12, 2–8 pm, Jac Leirner, who joined the gallery in 2019, will present Us Horizon. The exhibition will include a new work from Leirner's acclaimed series constructed from ensembles of shopping plastic bags and a new installation.

Jac Leirner is best known for her series of works employing specific everyday materials, such as banknotes, cigarette packaging, airline paraphernalia, business cards, and more recently items purchased in hardware stores.

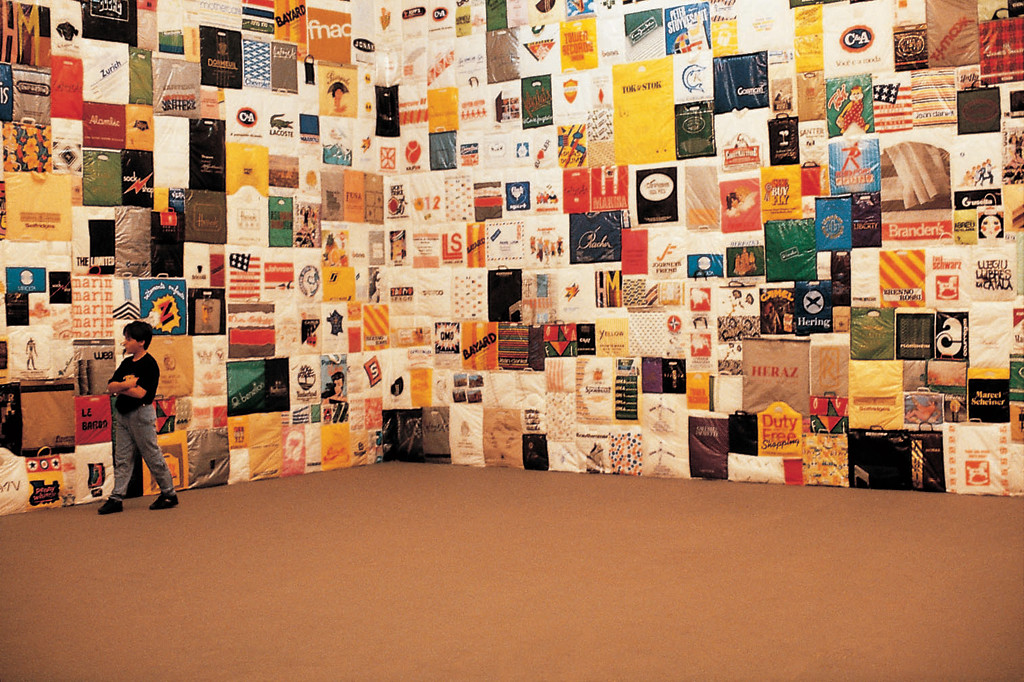

The central large-scale work, Us Horizon, presented in the upcoming exhibition, consists of over 200 vintage shopping bags installed in a double row at eye-level across three walls in the main gallery space.

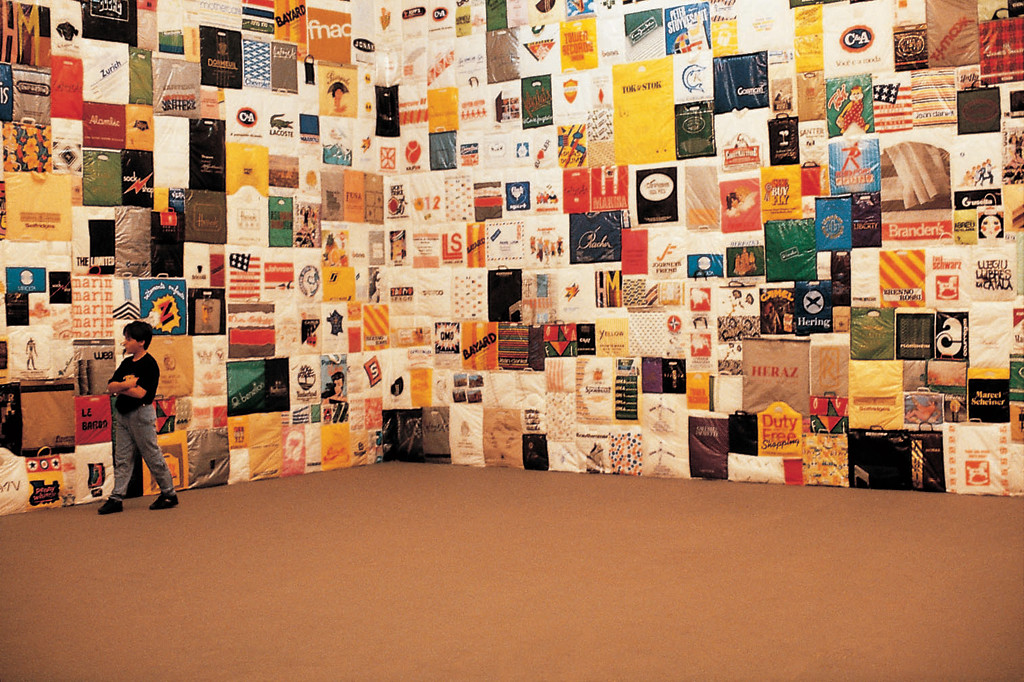

Leirner began collecting the material for this body of work in 1985 and first presented collections of plastic shopping bags at the 1989 São Paulo Biennial and the following year at the 44. Biennale di Venezia. Initially exhibited as vast quilted surfaces covering walls and at times also the floor, or as sculptures made from smaller groups sewn-together, later configurations were exhibited as large orderly grids, most recently at the Museum Ludwig, on the occasion of the artist’s receiving the 2019 Wolfgang Hahn Award. The double line of bags seen in Us Horizon constitutes a new and final format of this body of work. Assembled from individual shopping bags that date from the 1980s to today, Us Horizon’s linear sequence is organized according to their formal properties such as shape, color, and fonts. The bags attest to Leirner’s love of music, of books, refer to exhibitions she took part in or visited, to museums in which she exhibited, or which hold her works in their collections. Others were given to her by family and friends. In this format, as the title suggests, the work forms a horizon, both formally and symbolically: it represents the things that make us.

For a brief look at the history of this body of work, read below excerpts from Jac Leirner's conversation with Adele Nelson, published in full in the Conversaciones / Conversation series of the Fundación Cisneros/Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros in 2011.

|

|

|

| Jac Leirner, Nomes, 1989, Exhibition view: 20th Bienal de São Paulo, Brasil, 1989

| |

|

Adele Nelson: You exhibited Nomes, a series of works composed of stuffed and sewn plastic bags, in a solo exhibition in 1989 at Galeria Millan in São Paulo, a few years after you showed Os cem and Pulmão. As you mentioned earlier, you began to collect the plastic bags for Nomes around 1985 at the same time as you were collecting banknotes and cigarette packs. How did you select this seemingly quite banal material?

Jac Leirner: Like the cigarette packs and cruzeiro bills, the first bag just jumped out at me before I could make a choice. There was nothing special about it—a flowery print in uninteresting colors, without a logo, name, or words, thrown in a corner at home. But there it was, and I stared at it and thought, Wow, a bag!, as if it were the belle of the ball. And so I found myself at a new beginning. Again, it was another long, slow process, bag after bag after bag, meanwhile searching for technical solutions. A sewing machine, its operator—my dear Lucinha, Maria Lucia de Souza Suganuma—and polyester foam and buckram were perfect. I had sewn banknotes and laminated paper, and once again plastic bags were being sewn, in order to avoid glue or tape. I gave each bag a little body—some volume—using thick polyester. That was when I started to put them together. As I had articulated the banknotes with graffiti, I began to sort the bags based on color, name, design, logo; this included museum bags, which were doubly valuable. I was doing art, and the museum plus art meant two times art—art squared. I guarded these bags as if they were treasures.

|

|

|

| Exhibition view: Transcontinental – Nine Latin American Artists, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, 1990 | |

|

AN: You created many different forms with the plastic bags. There are sculptures placed on the floor, mounted to the wall, and suspended from the ceiling, as well as room-size installations where the walls and floor are completely covered.

JL: They are articulations. I deal with multiple factors at once—the material, its size, and what it offers for development. Each piece was the result of a different problem, and each material or each group of bags defined its own development. So, for example, I had many duty-free bags from the São Paulo airport. It took technically complex exercises to figure out how to sew many of these works. In some cases the resulting forms were like machines, mechanisms, or wheels, and they were complicated to create. In other cases, no. One piece simply presented an explicit color arrangement—just two bags, placed together because of their similar tonality, one sewn over the other.

AN: Aside from referencing your own field, visual art, what are the specific stakes of the works composed of plastic bags from museums, Nomes (arte) [Names (Art)] and Nomes (museus) [Names (Museums)]?

JL: The idea that bags leave museums on the verge of becoming trash moves me. They are reduced to their function as containers and then turned into museum detritus. Their lives are brief—but not the lives of the ones I rescued; those return to museums as parts of sculptural pieces. The bag’s tortuous path, between leaving the museum as trash and returning transformed into art, imprints time on the work and is the result of circulation, the basis of the circuit. The bag’s previous life before turning into material for sculpture remains part of its little story: “I was born here, I left, I was stuffed with polyester foam and sewn, and now I’m back, placed on the wall specifically to be looked at.” In silent ways materials tell their stories. They reverberate processes in different stages. They belong to networks and systems where they assume new positions, including, finally, that of an artwork placed in a museum. In the end, what I do in all the works is to create a place for things that don’t have one…

|

|

|

| Jac Leirner, Museum Bags, 1985-2019. Exhibition view: Wolfgang Hahn Prize, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2019. Photo: Gesellschaft für Moderne Kunst am Museum Ludwig/ Šaša Fuis, Cologne | |

|

| Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid 2022. Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

ARCOmadrid 2022

Booth 9B09 IFEMA MADRID Recinto Ferial, Av. Partenón 5 28042 Madrid Through February 27, 2022 www.ifema.es Esther Schipper is pleased to participate in ARCOmadrid 2022, through February 27. We hope you will join us at the fair, Booth 9B09. With works by: Rosa Barba, Matti Braun, Sarah Buckner, Angela Bulloch, Etienne Chambaud, Thomas Demand, Simon Fujiwara, Ann Veronica Janssens, Ugo Rondinone, Anri Sala, Karin Sander and Daniel Steegmann Mangrané. Daniel Steegmann Mangrané's new Holograms and General Idea's El Dorado Series from 1992, presented in ARCOmadrid's anniversary section, are highlighted below. If you wish to receive a dossier, or should you have any questions about our presentation at ARCOmadrid 2022, please contact Marek Obara: obara@estherschipper.com

|

|

|

| Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid 2022. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané |

|

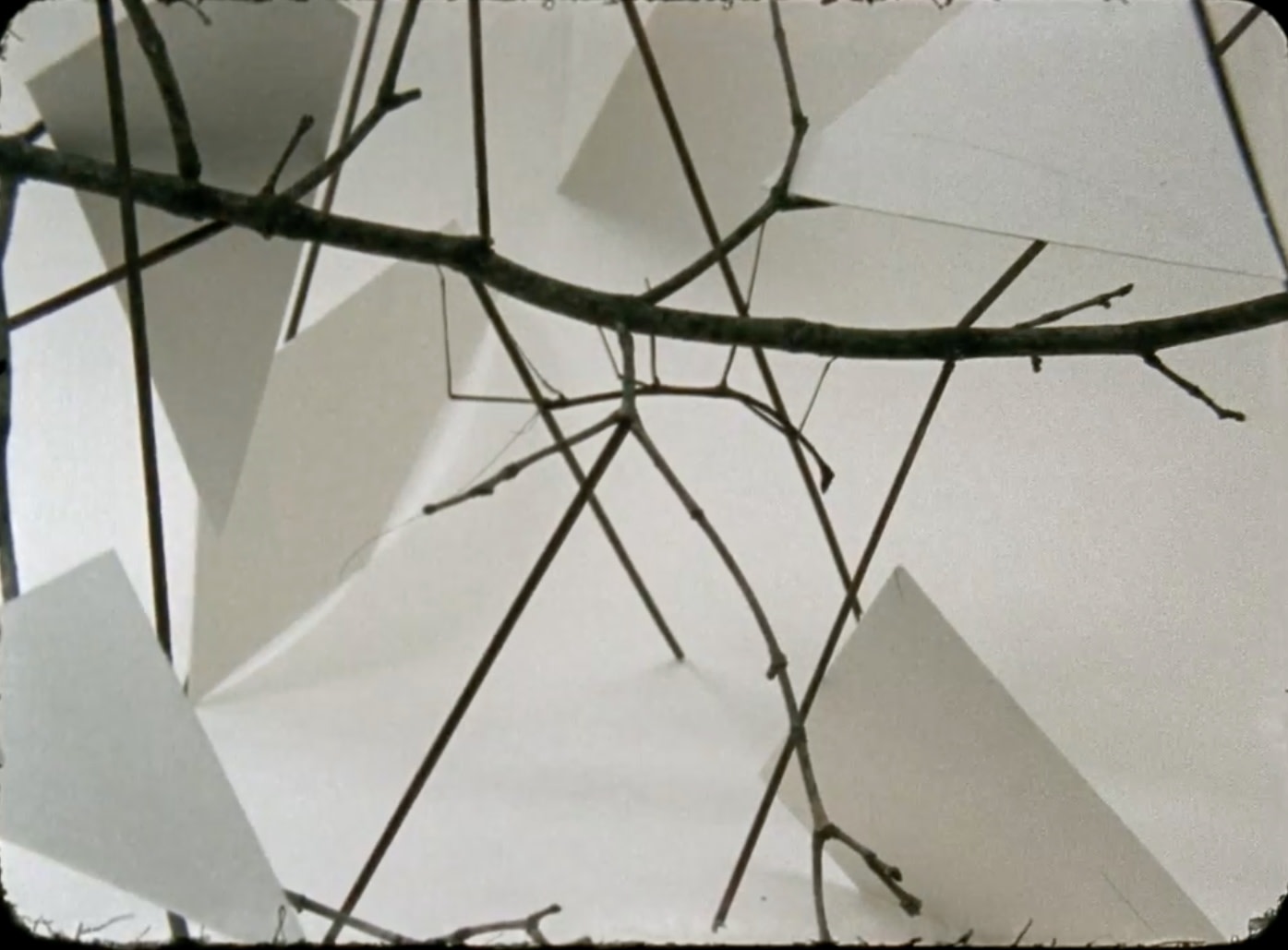

| Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Hologram (Mantis palace), 2021, pulse hologram, 25 x 20 cm, edition of 6.

Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid 2022. Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

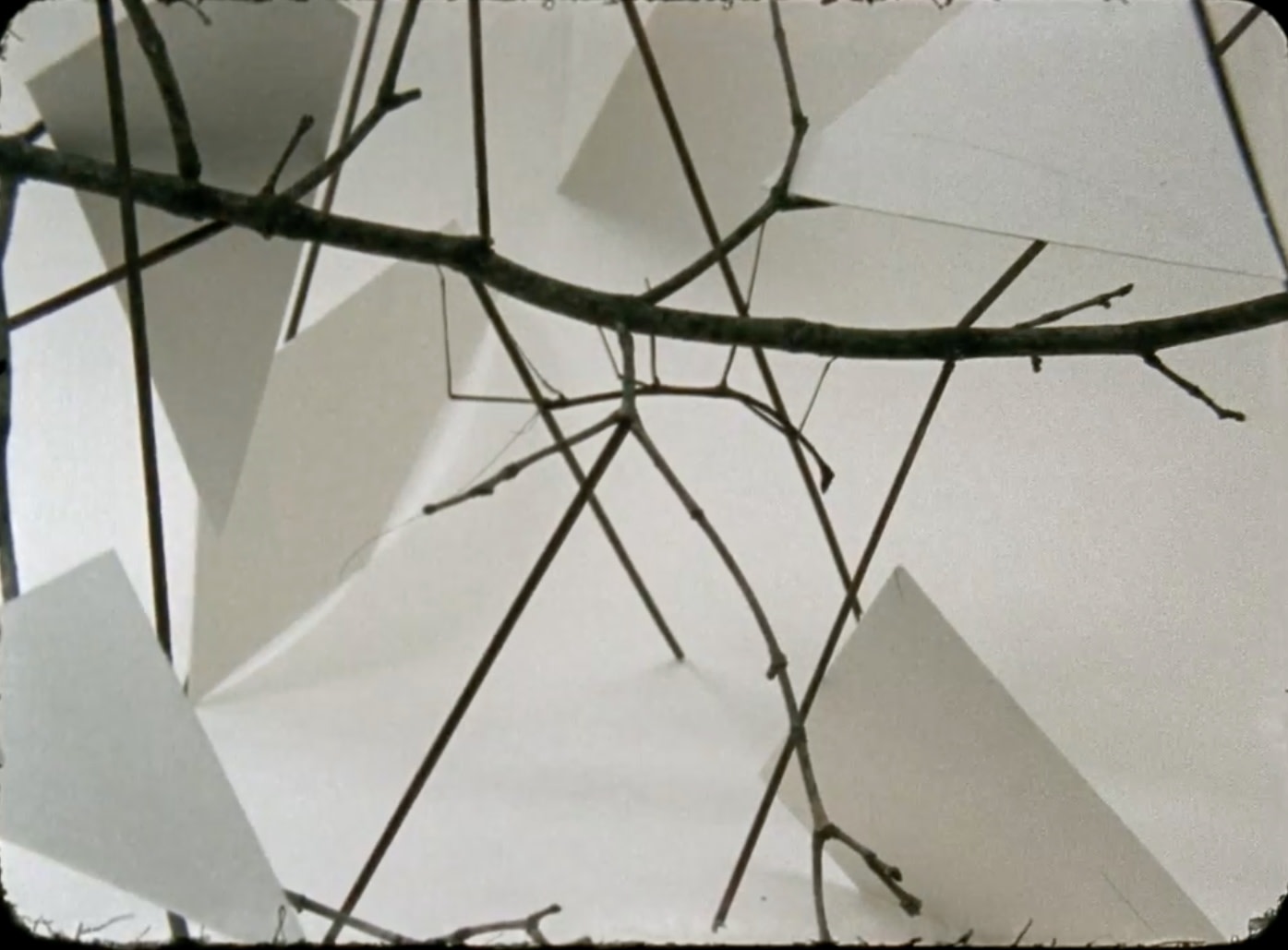

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané's new series of holograms continue the artist's longstanding interest in the relationship between organic and geometric forms.

Akin to a small terrarium or the display cases at a museums of natural history, the holograms create a small tableaux vivant of twigs, geometric shapes and, in some cases, insects. As one peers "into" the depicted space, trying to decipher what one is seeing, the arbitrariness of the distinction made between organic and human-made forms becomes apparent. In a reference to one of the artist's important early filmic works, Phasmides, 2012, the holograms bring together organic materials such as leaves and twigs, at times modified, with geometric shapes made from card board. Several works from the series include insects, among them leaf and stick insects and praying mantises.

|

|

|

| Front: Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Espacio Avenca, 2022, avenca branches, 95 x 28 x 28 cm (plinth).

Back: Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Hologram (Thicket), 2021, pulse hologram, 25 x 20 cm.

Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid, 2022. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

The use of technology in Steegmann Mangrane's practice always has a deliberate conceptual relevance. Working across many media, the use of digital scans or, in this case, holography draws attention to the influence technology can exert on the understanding of nature. The shifting connotations of the media becomes an integral part of the work. The nature of a hologram, namely that it compels the viewer to move in order to fully experience its three-dimensionality, lends itself perfectly to this suite of works. The notion of making the waves of light visible (in effect, the process in which holographic images are produced) has been a recurring theme in Steegmann Mangrané's practice, yet it is also the suggestion of movement inherent in the holographic image that here corresponds with the fascination the animal has exerted on humanity: famously mimetic and still, phasmids are generally recognized in nature only when they move. In addition, the spectral or ghostlike aspect of holograms finds a linguistic parallel in the phasmid, as their name is rooted in the Greek word for apparition or ghost: "phantasma" The Holograms are on view at our booth at ARCO and in March a selection will be included in Fata Morgana at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. Steegmann Mangrané's film Phasmides will be screened as part of the exhibition Mimicry—Empathy at la Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille.

|

|

|

| Film still: Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Phasmides, 2012, 16 mm film transferred to HD video, color, mute, duration 22:41 min, projection size 130 x 95 cm, edition of 6. © the artist | |

|

ARCOmadrid 40 (+1) Anniversary |

|

| General Idea, El Dorado Series, 1992. Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid 40 (+1) Anniversary, 2022.

Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

40 (+1) Anniversary | Booth 17

With AA Bronson and General Idea

Esther Schipper presents two historical works: General Idea's El Dorado Series,1992, and AA Bronson‘s Untitled (For General Idea), 1997 in this year’s special section ARCOmadrid's 40 (+1) Anniversary, through February 27.

General Idea's El Dorado Series, 1992, consists of a set of nine abstract paintings made of tinted hydrostone on extruded Styrofoam.

While the title references the mythical city of gold that lured 16th century Spanish conquistadors into the then-uncharted territories of South America, the nine tones of each colored hydrostone painting are pointillist interpretations of 18th century Spanish “caste” paintings in the collection of Museo Nacional de Antropología, Madrid, first commissioned during the reign of Philip V of Spain (1700-1746) to map out the development of different interracial ethnic groups in South America, as a result of European colonialism. Their subtitles identify specific types for each ethnicity: Sombujito, Morisco, Lobo, Coyote, Albarazado, Albino, Cuarteron, Mestizo, and Mulato. |

|

|

|

Las castas. Casta painting showing 16 racial groupings. Anonymous, 18th century, oil on canvas, 148×104 cm, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán, Mexico. | |

|

The work additionally refers to General Idea’s 1991 Maracaibo: ten collages of an extensive photographic archive belonging to a Venezuelan businessman who died of AIDS in 1988. The series of snapshots—representing hundreds of men of different skin color, either nude or dressed—was found by General Idea who appropriated it. Appropriation was central to many of General Idea’s artworks: the group drew on formats and aesthetics from sources in popular culture, archeology, and fine art.

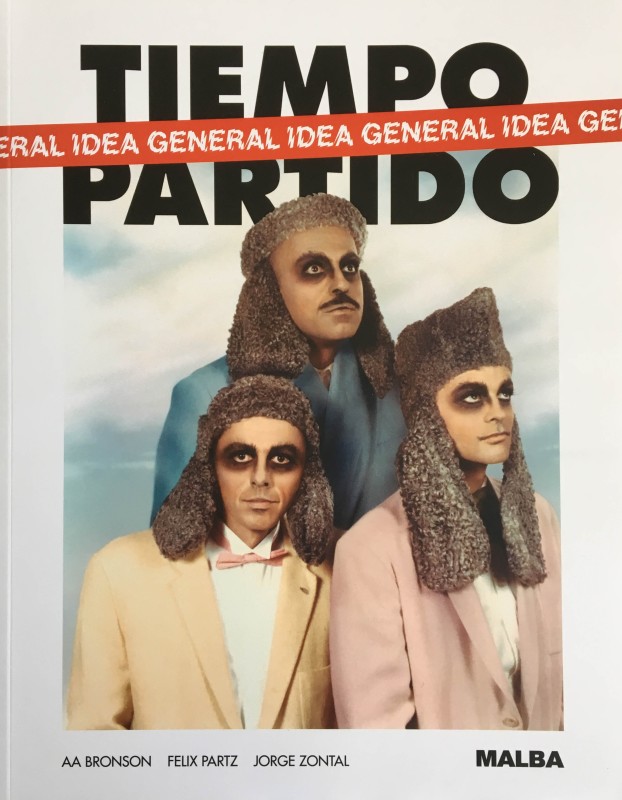

The work raised pressing and provocative questions linked to homosexuality, AIDS, class, and race. In the 2017 catalogue published by MALBA on the occasion of the major survey of General Idea's work at the Buenos Aires museum, Ivo Mesquita noted: “that material brought a new perspective to GI’s imagery and practices, one tied to cultural differences and differences in behavior, issues of class and race that arose through contact with a non-Anglo-Saxon context […] They wanted to restore the history of those bodies, to try to find a place for them in memory, a place that would not exclude them from history or hide the inequality that they represent.” (‘General Idea: Pages of History,’ Tiempo Partido, Buenos Aires: MALBA, 2017)

|

|

|

| General Idea, El Dorado Series, 1992. Photos © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

AA Bronson's Untitled (for General Idea) consists of three white Bertoia Side Chairs, an icon of mid-century modernist design, aligned in a row and outfitted with red, green and blue vinyl cushions. AA Bronson was co-founder of artists’ group General Idea with Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal in 1969, the three artists working and living together until the death of Partz and Zontal from AIDS in 1994.

Untitled (for General Idea) was the first solo work produced by AA Bronson after their deaths. The white Bertoia chairs and red/green/blue cushions were originally a gift from General Idea to Art Metropole, the center for artists books and editions that they founded in 1974. But after Jorge and Felix died, AA realized that the three chairs and cushions had become an icon of General Idea itself, or at least the memory of General Idea. He first exhibited it as an installation in 1997.

The three colors of the cushions reference the RGB color model of video and television displays. The color scheme appears frequently in General Idea’s oeuvre, which appropriated formats and aesthetics from sources in mass media, advertising and popular culture. It is the color scheme of General Idea’s iconic AIDS logo, a re-configuration of Robert Indiana’s widely quoted LOVE (1966) image to read “AIDS.” Producing posters, wallpaper, stamps, public sculpture and billboards, General Idea spread their self-described Imagevirus throughout art institutions and public spaces worldwide, in an attempt to normalize the word, and hopefully, normalize people’s relationship to the disease. As AA Bronson recounted at the time: “to make it something that can be dealt with as a disease rather than a set of moral or ethical issues.” |

|

|

| AA Bronson, Untitled (For General Idea), 1997. Booth view: Esther Schipper, ARCOmadrid 40 (+1) Anniversary, 2022. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

| Still: Christoph Keller, Anarcheology, 2014, HD video, silent, duration 12:40 min, edition of 4. © the artist

Images of tropical landscapes devoid of humans alternate with text passages, creating a haunting essay film about Western engagement with other cultures and about the encounters of written language with oral tradition.

| |

|

Anarcheology, Christoph Keller’s 2014 video work, is a travelogue on the fringes of what can be said or written—a text which deals with the spoken word and orality, in a film paradoxically silent. Juxtaposing three different rhetorical regimes, the video stages a performative contradiction between method and subject. The images suggest a voyage, departing from a bridge near Manaus and entering into the depths of Amazonia, a land apparently devoid of human traces. Black-and-white photographs alternate rhythmically with text inserts, leaving behind an afterimage that draws the viewer into an intermittent story. Christoph Keller’s work constitutes an examination of the history of science and of the way in which knowledge is gathered and organized. The artist's long-term projects concern, among other topics, anthropology (in particular the history of Western European engagement with the Amazon region), fringe science and parapsychology. Below an excerpt from a conversation on Anarcheology between the artist and Ana Teixeira Pinto, reprinted in full in Christoph Keller: Paranomia, Spector Books, 2016. The video is available to screen online through March 4 – watch here.

|

|

|

| Still: Christoph Keller, Anarcheology, 2014, HD video, silent, duration 12:40 min, edition of 4. © the artist | |

|

Ana Teixeira Pinto: Can you elaborate a bit on the concept of Anarcheology?

Christoph Keller: Anarcheology is a semiotic divisor splitting the world into halves, the archeological and the non-archeological. It is a term that evokes something not yet known. But what could the non-archeological be? Michel Foucault introduced the term in his lectures, Du gouvernement des vivants, at the Collège de France in 1980, saying that it was a wordplay for anarchy or anarchism— an attitude “concerning the non-necessity of all power.” The first part of the film touches on this.

ATP: In the film the only sign of a human presence is the concrete bridge of Manaus that appears in the very first images, almost like a symbol for an “archeological site of the future,” which is then subsequently left behind. Is the bridge meant to signify the connection between archeology and the modern state?

CK: The notion of archeology, generally speaking, is tied with nation-building. The discipline emerges in correlation with the nineteenth century occidental practice of legitimizing the power of nation-states by scientifically aligning their history with that of the ancient empires—most often from the south—which were hence publicly presented in museums or as displaced monuments. This practice recasts ancient objects as links in an evolutionary chain leading to the present powers, or more generally speaking, charges these objects as symbolic carriers of history. This archeological relation is still at work in many ways in which objects are displayed in exhibitions nowadays. |

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Baalbek Brazil Series, 2018, digital Fine Art inkjet print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, 50 x 300 cm (19 3/4 x 118 1/8 in) approx. (overall), ca. 50 x 300 cm (Installation), edition of 4. © the artist

Images of different flora specimens in vivid color are superimposed on the black and white photographs of the Lebanese ruins, that creates the impression of a herbarium—a collection of plants kept in-between book pages. As the title hints, the plants come from Brazil and were collected by the artist in the Mata Atlântica. This rainforest, stretching along the Atlantic coast of Brazil, is one of the most important biodiverse areas on Earth, yet is highly endangered, with only 7% of its original surface left.

| |

|

ATP: Your video has three, so to say, narrative blocks: the first describes a methodological conundrum, the second a personal story, and the third a Yanomami myth of origins. These three blocks refer to different temporalities. Does their juxtaposition signify the incommensurability between the present time of lived experience, the non-linear time of mythical tales, and the deferred time of written accounts?

CK: These different temporalities are present everywhere all the time: a written text becomes a lived experience in the moment you read it and lend it an inner voice. And when you imagine its narrative, it may become a non-linear mythical tale. On the other hand, oral traditions also have the ability to pass on information over very long timespans, like books do.

ATP: Your work often explores the limits of scientific discourse. Could one say Anarcheology points to the Yanomami as the frontier of a possible archeology of knowledge?

CK: In my view, the frontiers of a possible archeology of knowledge are the borders of our own archeological ways of thinking. That’s why artists are often more attracted to the fringes of science than to its mainstream. The Yanomami speak for themselves and their frontier is not an abstract concept, but rather a struggle for political and cultural autonomy and for the integrity of their way of life in the Amazonian forest.

|

|

|

Thomas Demand at Centro Botín |

|

| Exhibition views: Thomas Demand, Mundo de Papel, Centro Botín, Santander, 2021. Photos © Vicente Paredes | |

|

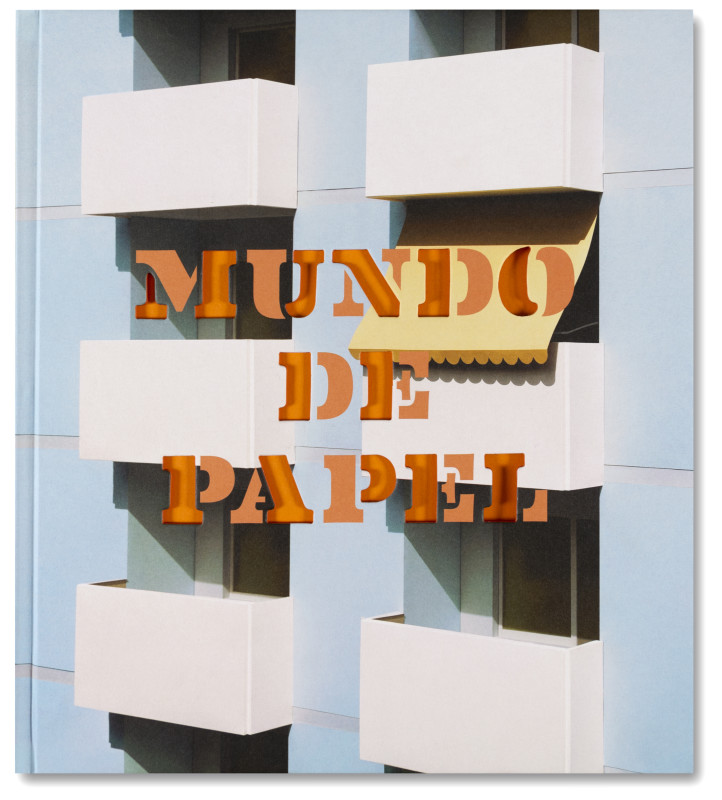

Thomas Demand's exhibition entitled Mundo de Papel remains on view at Centro Botín in Santander, on Spain's northern coast, through March 6, 2022.

In a recent interview with the French magazine Numéro, Demand spoke about the exhibition architecture developed in dialogue with the institution's building designed by Renzo Piano.

The beautifully produced catalogue—a pop-up book featuring the eight pavilions Demand conceived for the exhibition architecture—will be available in early March from MACK.

Centro Botín has launched an excellent virtual site of the exhibition that allows to navigate easily between rooms.

|

|

|

| Thomas Demand, Mundo de Papel. Limited edition artist's book, published by MACK (2022). Photo © MACK | |

|

Numéro art: The Centro Botin has allowed you to create a very special layout for your exhibition, a sort of “urban landscape.” Can you talk about this? Thomas Demand: The aim is to create an exhibition for the local public, i.e. people who are not necessarily so familiar with art. The Mundo de Papel exhibition is made up of about 30 photographs, plus eight pavilions. These pavilions, which hang from the ceiling and float about 30 cm above the floor, can be accessed by the public. Renzo Piano’s Centro Bot n stands on pilotis that you can walk around. Statically it’s very daring: it’s located by the sea and is partly built over the ocean, so it was necessary to balance it from an engineering point of view, resulting in a massive, heavy steel ceiling that is visually very dominant in the exhibition space. That’s why this ceiling is usually hidden behind some kind of cladding, but I find it very original, so I decided to hang my whole exhibition from it. So the room is just one single space? TD: Exactly, but the public can enter the eight pavilions suspended from the ceiling. There’s one that I call “Trump Tower,” which contains two works about Donald Trump. Then there’s a perfectly round pavilion that serves as a cinema for my films. Another is shaped like a labyrinth, another is reminiscent of 19th-century museums with stuccoed ceilings, and so on. The two long perimeter walls are lined with a kind of forest made of pipes, and the inside of the pavilions is also lined with various images, as well as instructions in folded paper.

Why this staging of works that already deal with the subject of staging?TD: Most museums have their own characteristics. Some have a single, large exhibition space. This puts limits on artists and makes it difficult for them to show their work. For me, an exhibition is much more than the sum of the pieces presented. For the public, this means that diving into a particular world, typical of your art, gains another dimension thanks to the staging of the exhibition.TD: Yes, the theatrical effect is both reinforced and adjusted, because normally the two-dimensional photograph replaces a three-dimensional model made in the studio. In the exhibition space, the three-dimensional effect becomes even stronger, without using the same means. And I have to admit that this extra dimension of the exhibition features amuses me, it makes me happy. The interview between Thomas Demand and Hans Peter Schwerfel was published in the fall issue of Numéro. Read the full interview HERE.

|

|

|

| Enter the virtual tour of the exhibition Thomas Demand, Mundo de Papel at Centro Botín, Santander | |

|

Hito Steyerl in The New Yorker |

|

A profile of Hito Steyerl in The New Yorker begins with the author, Merve Erme, encountering Steyerl in a virtual space, in Minecraft.

"It would be wrong to claim that I first met the German artist Hito Steyerl on such-and-such day, in such-and-such city, where the weather was bright or blustery, and that she arrived suitably dressed for this season or the next. It is more accurate to say that she simply appeared while I was waiting in the atrium of the Communist Party court, under a spectacular red banner from which the faces of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin bore down on me...." |

|

|

Rodney Graham and Andrew Grassie at Whitechapel Gallery |

|

| Rodney Graham, The Gifted Amateur, Nov. 10th, 1962 (2007) three transmounted chromogenic transparencies in painted aluminum light boxes, each: 285.7 x 182.9 x 17.8 cm, overall: 285.7 x 555.3 x 17.8 cm. © the artist | |

|

Whitechapel Gallery presents a 100-year survey of the studio through the work of artists and image-makers from around the world. Whether it be an abandoned factory, an attic or a kitchen table, it is the artist’s studio where the great art of our time is conceived and created. In this multi-media exhibition, the wide-ranging possibilities and significance of these crucibles of creativity take centre stage and new art histories around the modern studio emerge through striking juxtapositions of under-recognised artists with celebrated figures in Western art history. The exhibition brings together more than 100 works by over 80 artists and collectives from Africa, Australasia, South Asia, China, Europe, Japan, the Middle East, North and South America. They range from modern icons such as Francis Bacon, Louise Bourgeois, Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele and Andy Warhol, to contemporary figures such as Walead Beshty, Lisa Brice, Andrew Grassie and Rodney Graham. " Go if you possibly can. This is nothing less than a history of art by other means; a magnificent way of entering the minds of artists through the places where they worked, and what they made there." This is the conclusion of Laura Cumming's rave review in last Sunday's Guardian. Read the full review HERE.

|

|

|

Simon Fujiwara at Esther Schipper |

|

| Photos © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

Don't miss your chance to visit the Whoniverse!

Simon Fujiwara's Once Upon a Who? remains on view at the gallery in Berlin only through tomorrow, Saturday, February 26. |

|

|

Simon Fujiwara at Hamburger Kunsthalle |

|

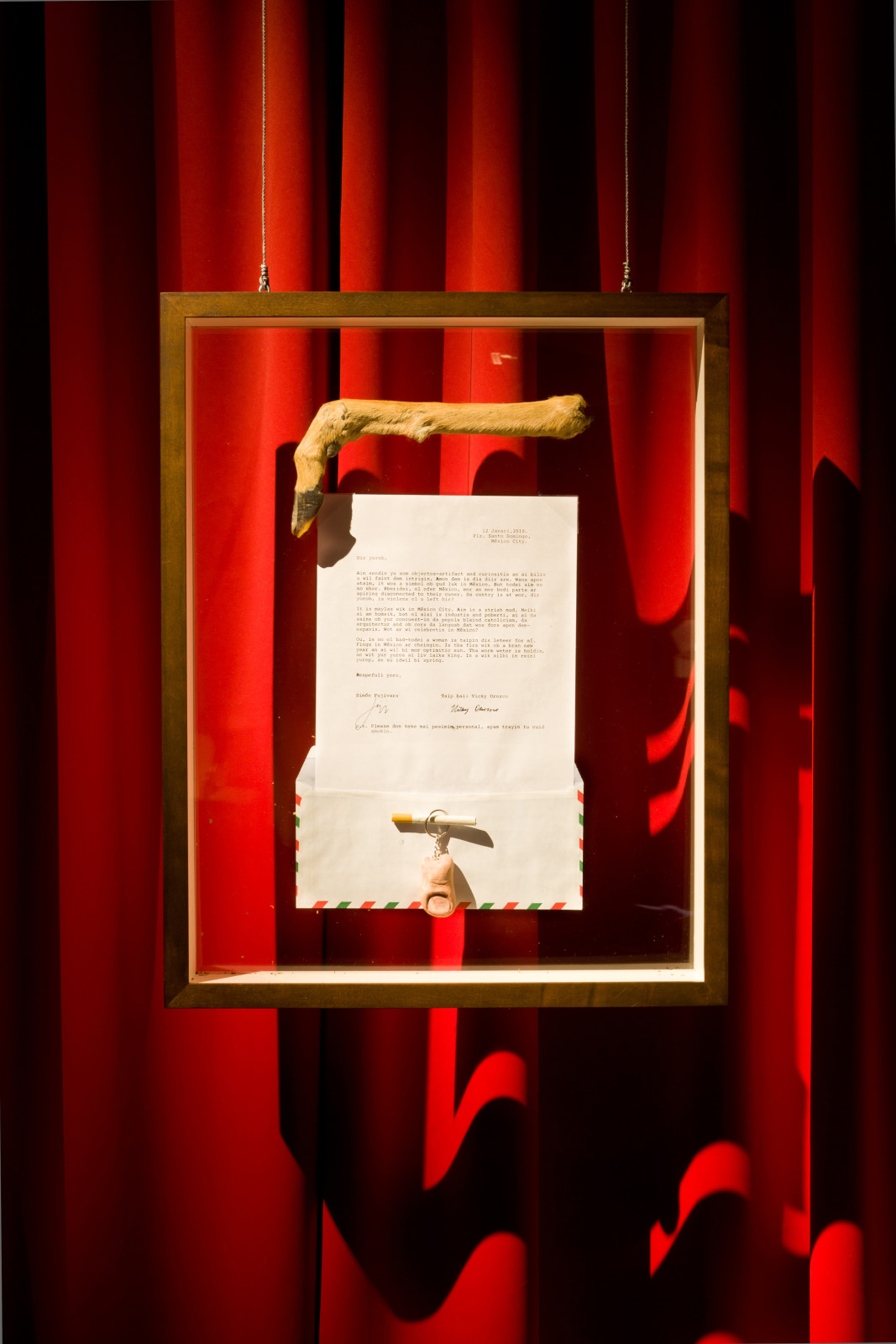

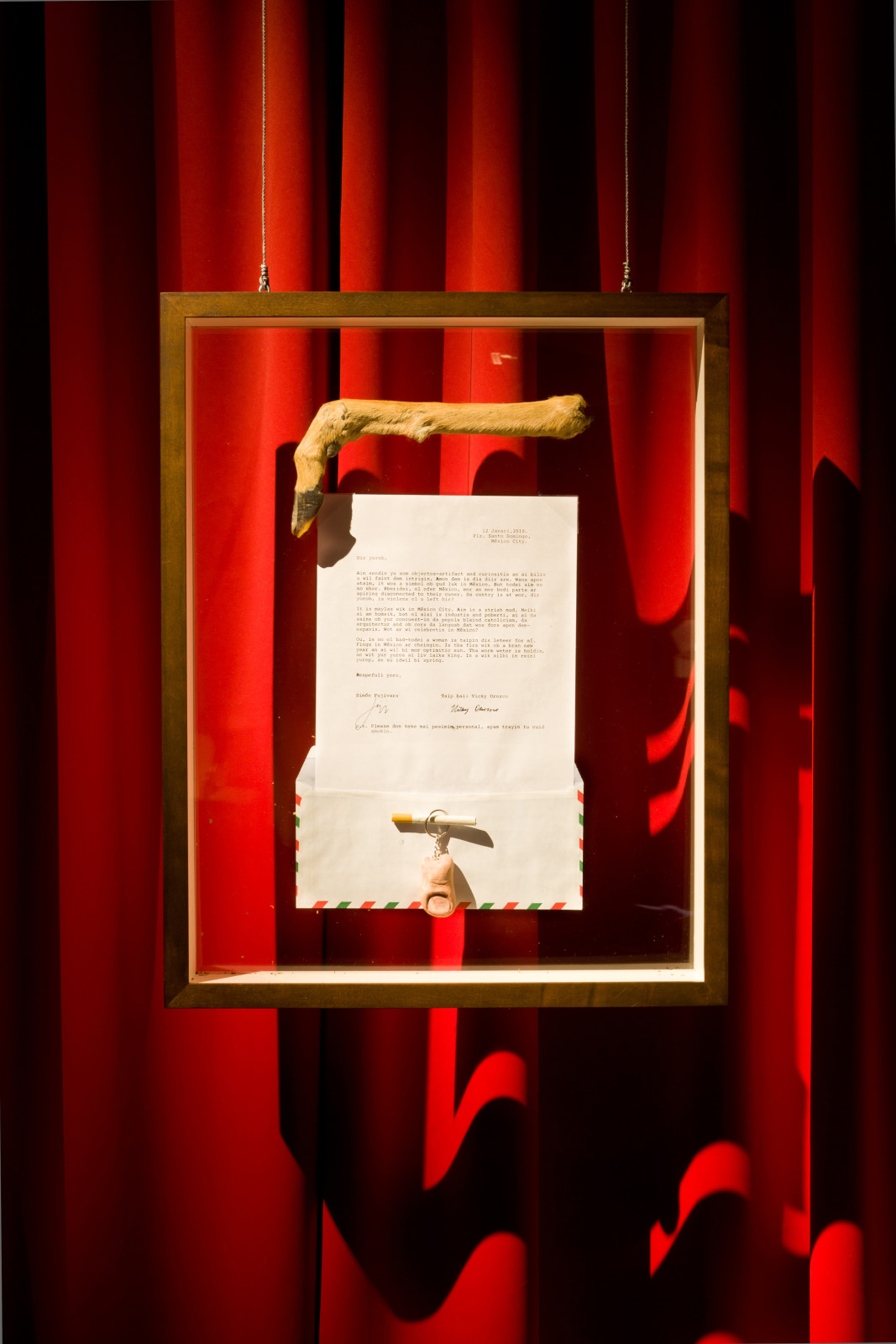

| Simon Fujiwara, Letters From Mexico, 2011, Mixed media, dimensions variable. Exhibition view: ARCHIVE UND GESCHICHTE(N), Hamburger Kunsthalle 2011. Photo © Hamburger Kunsthalle | |

|

The exhibition something new, something old, something desired places the Kunsthalle’s important collection of contemporary art in an exciting dialogue with recent acquisitions of the latest works. The themes that come to the fore spotlight the urgent issues of our day: questions of understanding and communication, isolation and marginalisation, power and protest, utopia and structure. At the same time, the show explores (virtual) worlds and realities on the basis of architectural designs while addressing the tension between form and dissolution and focusing attention on the potential for interconnecting material and language.

On view is Simon Fujiwara's 2011 Letters from Mexico which consists of letters, various additional documents, artifacts and objects installed on a wall covered with three colored curtains, creating an installation that takes its origin from a performative scenario in which Simon Fujiwara visited a square in Mexico where letters can be dictated for persons not able (or willing) to write. The artist instructed the writers to transcribe the sounds. The letters thus make manifest the misunderstandings of phonetic understanding, doubling as a misunderstanding between cultures and continents, between colonizers and colonized, conqueror and suppressed.

The artist described his visit to Mexico in a subsequent catalogue:

"Wandering the streets of Mexico City over the winter of 2010, I came across the Plaza Santo Domingo, a flagstone square flanked by colonial buildings bustling with vendors selling all things related to writing, paper, and printing. What a romantic scene to see in 2010, I thought to myself! On one side of the square under a set of colonnaded shop fronts sat a row of typists, and beside them members of the general public, many of them illiterate, dictating letters. I was struck by the scene-it was like a performance-the air-bound words passing between speaker and transcriber, words captured and turned into small black hieroglyphs, frozen in time on paper. I took a seat beside an idle typist and began to speak to him in English, which he didn't understand. 'Write what you hear,' I told him, 'not what you think I am saying,' and after much protesting he began to transcribe phonetically what I said:

Dir Europ, this seris of leters wer dictateitet in lnglish and transcraib bait ha strit taypists of Plz. Santo Domingo in Mexico City durin my stei ov winter 2010-2011. Thei mark da hondret years ov independens from Spein sins da Mexican Revolucion. Tha leters wor inspair bai Heman Cortes, di Spanis conquistador hu descraibt that 'discoveri' ov Mexico in leteres tu da king of Spain.

So began the first letter. I began to speak about my observations of Mexico-about the troublesome political situation, the scenes on the streets-musings of a tourist with a conscience. I began to describe the typists themselves, unbeknownst to them.

Dear Mexico, Forgive me but I am only European:

When money does not work there is persuasion.

When persuasion does not work there is aggression.

When aggression does not work there is no remedy, only poetry."

The title of the work echoes the "Letters from Mexico" by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. In five letters sent to the Spanish king Charles I, Cortés gave his personal account of the expedition that overthrew the Aztec empire in 1521. Like Cortés's, Fujiwara's letters – framed and displayed alongside memorabilia of his journey – also relate his experience as a European in Latin America, from his initial enthusiasm for Mexican culture to his later disenchantment with the country's social inequalities and violence.

|

|

|

| Simon Fujiwara, Letters From Mexico, 2011, Mixed media, dimensions variable. Exhibition view: ARCHIVE UND GESCHICHTE(N), Hamburger Kunsthalle 2011. Photo © Hamburger Kunsthalle

| |

|

|

|

Simon Fujiwara

Who The Bær

2021

Publisher: Fondazione Prada

Language: Italian, English

Available here

|

|

General Idea

Tiempo Partido

2017

Publisher: Malba

Language: Spanish (with English appendix)

Available here

|

|

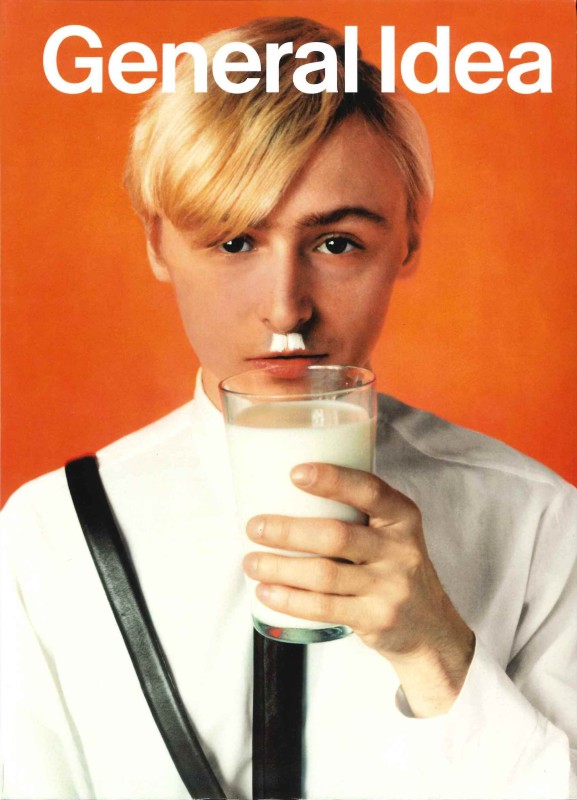

General Idea

Haute Culture: A Retrospective 1969-1994

2016

Publisher: JRP|Ringier

Language: English

Available here

|

|

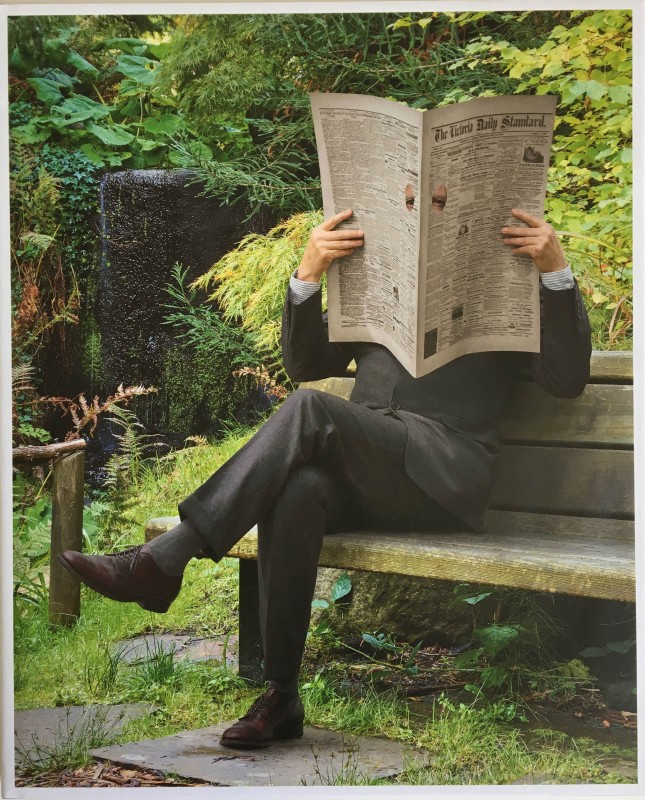

Rodney Graham

Lightboxes

Publisher: Museum Frieder Burda

Language: German, English

Available here

|

|

Andrew Grassie

2012

Publisher: Rennie Collection

Language: English, French

Available here

|

|

Christoph Keller

Paranomia

2016

Publisher: Spector Books

Language: French, English

Available here

|

|

Jac Leirner

in conversation with Adele Nelson

2011

Publisher: Fundación Cisneros/Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros

Language: English, Spanish

Available here

|

|

Jac Leirner

Add It Up

2017

Publisher: Fruitmarket Gallery

Language: English

Available here

|

|

Jac Leirner

Wolfgang-Hahn-Preis 2019

2019

Publisher: Walther Koenig

Language: German, English

Available here

|

|

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané

A Leaf-Shaped Animal Draws The Hand

2020

Publisher: Skira

Language: Italian, English, French

Available here

|

|

|

|

|