Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version unseres Briefes aus Berlin!

Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! This week we continue our film streaming with Tao Hui’s Mongolism from 2010. (Please note these weekly viewing links are temporary: The film is available to view only through Sunday night, Berlin time.) As Spring turns into Summer, in this Letter from Berlin Isabelle Moffat presents two outdoor projects : Martin Boyce’s 2019 commission at Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute and Pierre Huyghe’s La Saison des Fêtes from 2010, including an exclusive screening of Huyghe's film on his Documenta project, A Way in Untilled! In four short videos, Isa Melsheimer speaks about her transformative experience on the coast of Newfoundland. This week’s theme was loosely inspired by Para Site’s large-scale group exhibition entitled Garden of Six Seasons that includes Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s work Gloria. More information below. Anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our digital platform. Read this in good health.

|

|

|

Tao Hui — This weekend's online film screening |

|

| Tao Hui, Mongolism, 2010, single channel video (color, sound), duration: 30:01 min

Film still © Tao Hui | |

|

There’s a Chinese neologism, jiediqi, which first came into vogue on the internet and loosely translates as “down-to-earth.” More precisely, it describes a person or endeavor as being firmly in tune with the energy and climate of a particular locale. I cannot think of a word that more precisely captures Tao Hui’s work. Laden with Chinese pop-cultural references, his visceral, intuitive videos and installations give voice—with humor and poignancy—to the rapidly evolving Chinese milieu amid the omnipresence of media.

Every You Every Me: Tao Hui, Alvin Li, Mousse Magazine, Spring 2020

Tao Hui was born in 1987 in Yunyang, Chongqing, in southwestern China and now lives and works in Beijing. The artist creates immersive video-installations that bend the boundaries of fiction and reality to address cultural and identity related issues. His works are visceral and provocative, yet enlightening and always imbued with a strong emotional power and a sense of displacement, inviting the viewers to confront themselves with their own cultural history, ways of living and social identities.

Mongolism is among Tao Hui's very early films, produced when the artist was still in art school at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing. The characters of Tao Hui's early films are loosely based on popular costume dramas from 1990s Chinese television, among them The New Legend of Madame White Snake and My Fair Princess.

Shot in brilliant color, the film follows a young protagonist clad in bright green historical costume. Yet from the beginning, narrative levels are interwoven as a contemporary figure is shown putting on make-up and dressing up. While the enigmatic figure is seen walking around a landscape, urban areas, parks and streams, fantasy and contemporary reality mix. A number of other figures accompany this main figure and recur throughout the film: among them a woman in a raincoat following it and rescuing it from the water; a marching band of women dressed in red, a monk-like figure, and finally a group of characters in historical and contemporary clothes. Except for one line, there is no dialogue, only ambient noises: dripping of water, animal sounds, singing, and the percussive rhythms of the marching band's playing. The single line appears roughly in the center of the film and seems crucial to the understanding, as it also gives the film its title: "I am a Mongolian, not Muslim," the green-clad figure says.

The film's striking visual style and juxtaposition of fantastic and contemporary elements make Mongolism an early example of Tao Hui's experimental storytelling that explores the narrative conventions of mass-media productions in today's mediatized reality.

For more information on the work of Tao Hui please see below the recent text by Alvin Li in Mousse Magazine. |

|

|

Martin Boyce — Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute

|

|

| Martin Boyce, An Inn For Phantoms of the Outside And In, 2019, Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute.

Photos © Keith Hunter | |

|

Over the years I’ve photographed a number of abandoned or disused tennis courts and I’ve collected similar images from books or cut from magazines. There is something fascinating about this rectangle of chain link fence that at once demarcates one place from another, one delineated use or activity from another. Equally fascinating is how over time this idea of use can shift, from organised tennis games to more improvised versions of play to, in a state of disrepair, a place to meet and hangout. It is this in between state that interests me.

Martin Boyce

Almost exactly a year ago Martin Boyce’s An Inn For Phantoms of the Outside And In was inaugurated at Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute in Scotland.

Seen from a distance, one might imagine encountering an abandoned tennis court. Close up, the incongruities of the elements in this enclosure manifest more clearly. Inspired by a story about a long-abandoned tennis court from the 1970s elsewhere in the grounds of the gardens, Martin Boyce placed his outdoor sculpture in the midst of a pastoral-looking landscape. While the improbable sight of a telegraph poles with geometric lampshades or a large off-white disc from perforated steel is at first surprising—more in line with the dilapidated yet enchanted urban environments evoked by Boyce’s exhibitions that appear inhabited by slightly laconic witnesses of past urban development programs—the setting also emphasizes the organic references that underlie his formal vocabulary of chain-link fences, chains, and fragments freed from quotidian usefulness. Landscape begets landscape.

At the same time, the enclosure acts as a frame, both formally as the elements within are placed in a more uniform setting, but also experientially, as the perspective of visitors radically shifts upon entering the gravel-covered inside: now they join the objects being looked at from the outside. The fabric that is draped over parts of the fence recalls the paradoxical use of curtains in some of the most iconic modernist buildings such as Mies van der Rohe’s mid-twentieth century Farnsworth House, conceived as an architecture of transparency yet shielded from outside views. In this context the notion of the threshold, a recurring theme in the artist’s conceptual framework, comes into play and here can be experienced in all its dialectical instability.

|

|

|

At the time it was installed, Boyce, asked about the maintenance of the work, instructed “do nothing, don’t pick up fallen branches or leaves, I don’t want anything swept up.” Even before Boyce gave nature the opportunity to encroach, he had already added signs of decay or dilapidation to the chains, fence and other elements of An Inn For Phantoms of the Outside And In. (You can watch part of this process in the video linked below.) But he was also counting on time as collaborator: “That idea of architecture and man-made landscaping is this attempt to control nature, but it really only takes moments and nature takes it back again, reclaims it. I really like the idea of capturing the tipping point as nature reclaims a space and allowing the viewer to step into that moment.”

Apart from the paradox of its setting, it is also the combination of unlikely shapes and materials recalling both industrial and organic sources that give the work a quality of being suspended in an in-between state. Its dreamlike quality—the way in which objects, and people, in dreams can simultaneously be understood as one thing and register as another—is beautifully captured in a text by architectural historian Beatriz Colomina from the catalogue:

A table that is not a table. A fireplace that is not a fireplace. A curtain that is not a curtain. Lamps that are not lamps. Even the fence does not really fence. lt does not match the gravel below, heading out into the grass at an angle, and the gravel is not a rectangle. Everything is askew. And yet all these things that are not quite themselves collaborate to produce the palpable sense of a place, even of the sound of tennis balls hitting the mesh of racquets, the swish, the grunt, the laugh, 'love', 'hold', 'break', 'let', 'fault', 'out'... Things that are almost not there construct a ghost architecture, an abandoned tennis court that might have been there, or dreamed about.

Extended into 2020, the work is still in place, even as it remains inaccessible because of current lockdown requirements.

|

|

|

Pierre Huyghe —La Saison des Fêtes

|

|

| Watch a time-lapse video of the of installation of La Saison des Fêtes at Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo from 2016.

| |

|

Pierre Huyghe’s La Saison de fêtes was first presented at the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid.

The building represented a very specific cultural and historical setting, as the artist subsequently noted: “The Palacio de Cristal was built as a separated, acclimated world, an exhibition space for exotic plants brought back from a geographic elsewhere, the other side of the globe, the colonies, and maintained in the artificial climate of a glass house. The conquest of space shifts to the conquest of time for La Saison des Fêtes, the “where” becomes a “when.” Living organisms, common plants attached to recurrent cultural, social, religious events are represented. It is both a vegetal annual cycle and a symbolic calendar, a garden of celebrations where biological and historical time enter into friction with another.”

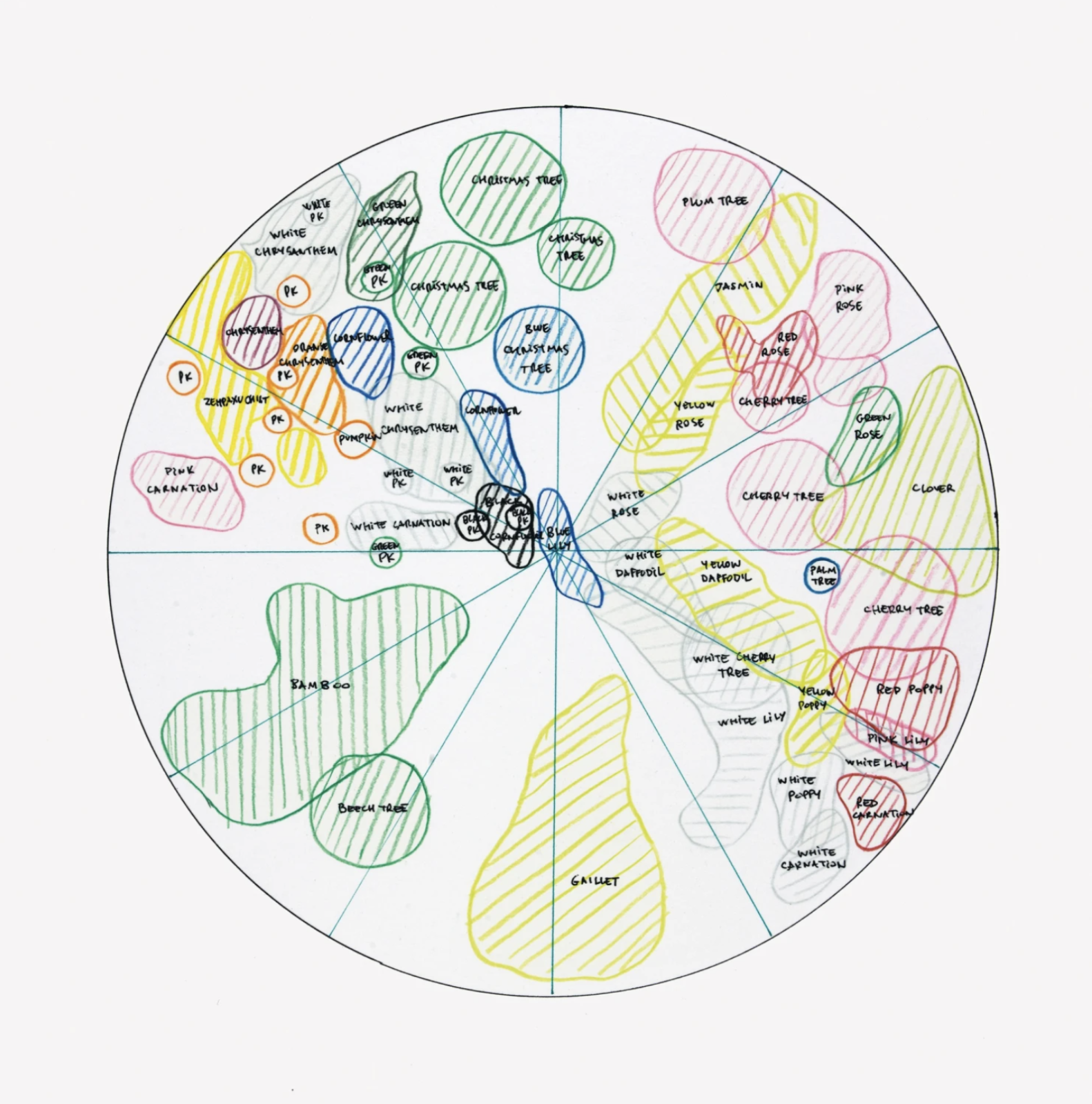

A site-specific garden, La Saison des Fêtes takes up the function of a calendar and the form of a clock's face, on which the vegetation is positioned in a circular sequence following their seasonal appearance. The plants Pierre Huyghe included in this man-made landscape are often associated with popular festivals and holidays around the world, such as red roses of Valentine's Day, pumpkins of Halloween, or Hanami cherry blossoms that traditionally mark the start of spring in Japan. The many plants, which usually bloom at different moments in the year were supposed to grow and blossom simultaneously when the work was first presented |

|

|

| Exhibition view: Pierre Huyghe, La Saison des Fêtes, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía – Palacio de Cristal, Madrid, 2010

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020 Photo © Pierre Huyghe | |

|

At its permanent site at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the work was adapted to the Dutch climate and certain plants were exchanged. For the work to continue its calendric function—its specific planting in the round in twelve segments corresponding to the months of the year—human intervention is needed on a regular basis. Having created a man-made landscape, it requires upkeep. This marks a difference from subsequent projects that more explicitly embrace the effects of entropy.

For those later projects—among them Untilled at dOCUMENTA 13 or the 2017 After ALife Ahead—another work was ground-breaking: The Host and the Cloud. Bringing together and developing further key themes, among them the staging of exhibitions as time-based experiences, an interest in rituals, the integration of chance and arbitrary elements, and the generation of fictional scenarios for a group of persons, the work on this film constitutes an important turning point.

|

|

|

| Artist's Diagram: Pierre Huyghe, La Saison des Fêtes, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía – Palacio de Cristal, Madrid, 2010

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Photo © Pierre Huyghe | |

|

Set in a building that once housed the Musée national des Arts et Traditions Populaires in Paris, which had been just closed, the staged experiment, also called The Host and the Cloud, lasted three days. It was filmed on Halloween 2009, Valentine’s Day and May Day of 2010. A live audience witnessed the event. From the footage shot during these three days and nights, the film The Host and the Cloud was produced. After conceiving a set of rules, Huyghe let the situation develop on its own. The film shows a variety of human behaviors, from scenes that appear staged and formal to improvised bacchantic group interactions. It shows how group dynamics may change when exposed to unexpected influences.

Especially the creation of speculative situations has since come to the forefront of Huyghe’s practice. In an interview from 2013 the artist described this development: “You frame a rule, set a condition, but you cannot determine how a given entity will interact with another. What is presented is a set of elements and the way they collide, confront and agree with each other. I don’t want to exhibit something to someone but exhibit someone to something.” Pierre Huyghe’s work continues to undifferenciate the boundaries between art object and nature, between human and nonhuman intelligences, between scripted action and contingent situation.

|

|

|

| Pierre Huyghe, A Way in Untilled, 2012, HD Video in color, sound, duration: 14 min

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020. Film still © Pierre Huyghe

| |

|

Isa Melsheimer — Fogo Island

|

|

| View out the window from the artist residency. Photo © Isa Melsheimer

| |

|

Isa Melsheimer is best known for her engagement with architecture, yet nature plays an important role in her practice: plants have long been part of her exhibitions and the self-regulating ecosystems of her Wardian cases, while her gouaches have introduced fantastic flora and fauna into their architectural locations, And since her 2017-18 artist residency on Fogo Island in Newfoundland on Canada’s Atlantic coast, oceanic creatures and wild seascapes began to appear in her work, more decidedly representing the symbiotic (even parasitic) relationship of architecture with its natural surroundings.

This notion goes hand in hand with the idea of a metabolism of architecture—almost an animistic notion of the house not as machine but as living organism—imbuing her works in recent years, perhaps also as a function of the global ecological crisis. She has always read broadly—a mix that surfaces in her work: literature, dystopian science fiction, feminist and post-humanist philosophy, ecological thrillers--but arguably the experience of her artist residency in the rugged coastal landscape of Fogo Island added another level of urgency to her preoccupation with nature.

In the four short videos produced by the non-profit Berlin exhibition space KINDL on occasion of the artist’s major solo exhibition (which is now open to visitors again) Melsheimer speaks about the impact of her stay.

|

|

|

Postscript

In 2018 Isa Melsheimer's installed a number of small ceramic works as part of a group exhibition in a park north of Berlin, playing on their naturalistic appearance. The small glazed ceramics are modelled on rare Japanese Matsutake mushrooms. The mushroom--the most valuable in the world--is the point of departure for Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's best-selling book examining the relation between capitalist destruction and collaborative survival within multispecies landscapes, entitled The Mushroom at the End of the World. Unsuspecting wanderers and seasoned gallery goers alike tried to pick them. |

|

|

| Isa Melsheimer, Matsutake, 2018, glazed ceramic, dimensions variable, unlimited edition. | |

|

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster — Para Site

|

|

The large-scale group project Garden of Six Seasons, with Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s 2008 work Gloria, opens today at Hong Kong’s Para Site.

For me being in Brasilia and Chandigarh is like coming home. I recognise the architecture of my childhood there. In the tropics, the contrast between what’s geometric and organic is so vital that it brings back memories.

—Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster quoted in Marie Darrieussecq, “Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster,” Art Review, October 26, 2008, 96.

The film is situated in a park in Rio de Janeiro, which is designed in the style of French garden architecture with fountains, statues and benches. Around the park an urban environment is visible. Both the cars in the background and the fountains compose the soundscape as well as the shouts of children playing in the park. The subtitled narration imagines a possible film sequence that could be realized in the park depicting Oscar Niemeyer and Manuel de Oliveira sitting together on one of the benches. It starts to snow.

|

|

|

A new pattern coming out of an old one, shared from Martin Boyce's Instagram

Martin Boyce has reworked and reformulated iconic design objects, developing his own pictorial language based on a reading of the formal and conceptual histories of design, architecture and urban planning. While Boyce’s oeuvre includes shapes drawn both from modernist and classic design sources, it also includes references to everyday urban objects, such as fences, trash bins, or telephone boxes. |

|

|

Journey Through the Gallery

|

|

| Exhibition view: Tomás Saraceno, Algo-r(h)i(y)thms, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2019

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

In this next instalment of Journey Through the Gallery, we look back to November 2019 where we presented Algo-r(h)i(y)thms, Tomás Saraceno's third solo exhibition with the gallery. See inside the exhibition here

|

|

|

Welcome to the next instalment of the series where our artists open their studio doors and invite you to guess whose studio.

To help figure out whose studio you’re visiting, we’ve put together a number of clues to get you on the right track:

1. Has been with the gallery for over 30 years

2. The sky's the limit

3. Loves rules

4. Enjoys heavy metal |

|

|

|

|