Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version unseres Briefes aus Berlin!Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! This week we take the launch of our Ari Benjamin Meyers Online Viewing Room as occasion to loosely focus on music in this Letter from Berlin. We introduce Meyers’ with a film streaming of his 2018 Four Liverpool Musicians and a text by Alexander Abdelilah. You can also find Meyers recent talk with Michael Langer in German public radio linked. (Please note these weekly viewing links are temporary: The film is available to view only through Sunday night, Berlin time.) In a recent conversation with the Vienna-based curator Alexandra Grimmer, Liu Ye spoke about listening to music in his studio.

Ryan Gander has practiced his DJ-ing skills. See, and listen to, his broadcast, recorded on his birthday. Anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our digital platform. Read this in good health.

|

|

|

Ari Benjamin Meyers Four Liverpool Musicians – This weekend’s online film screening

|

|

| Ari Benjamin Meyers, Four Liverpool Musicians (Bette, Budgie, Ken, Louisa), 2018, three channel video, color, sound, four original scores, framed, duration 52:10 mins, scores: 4 framed score triptychs, 3 score pages each (30,1 x 23,2 cm each score page, 49,5 x 95,3 x 2,3 cm each framed triptych)

Film still © Ari Benjamin Meyers

| |

|

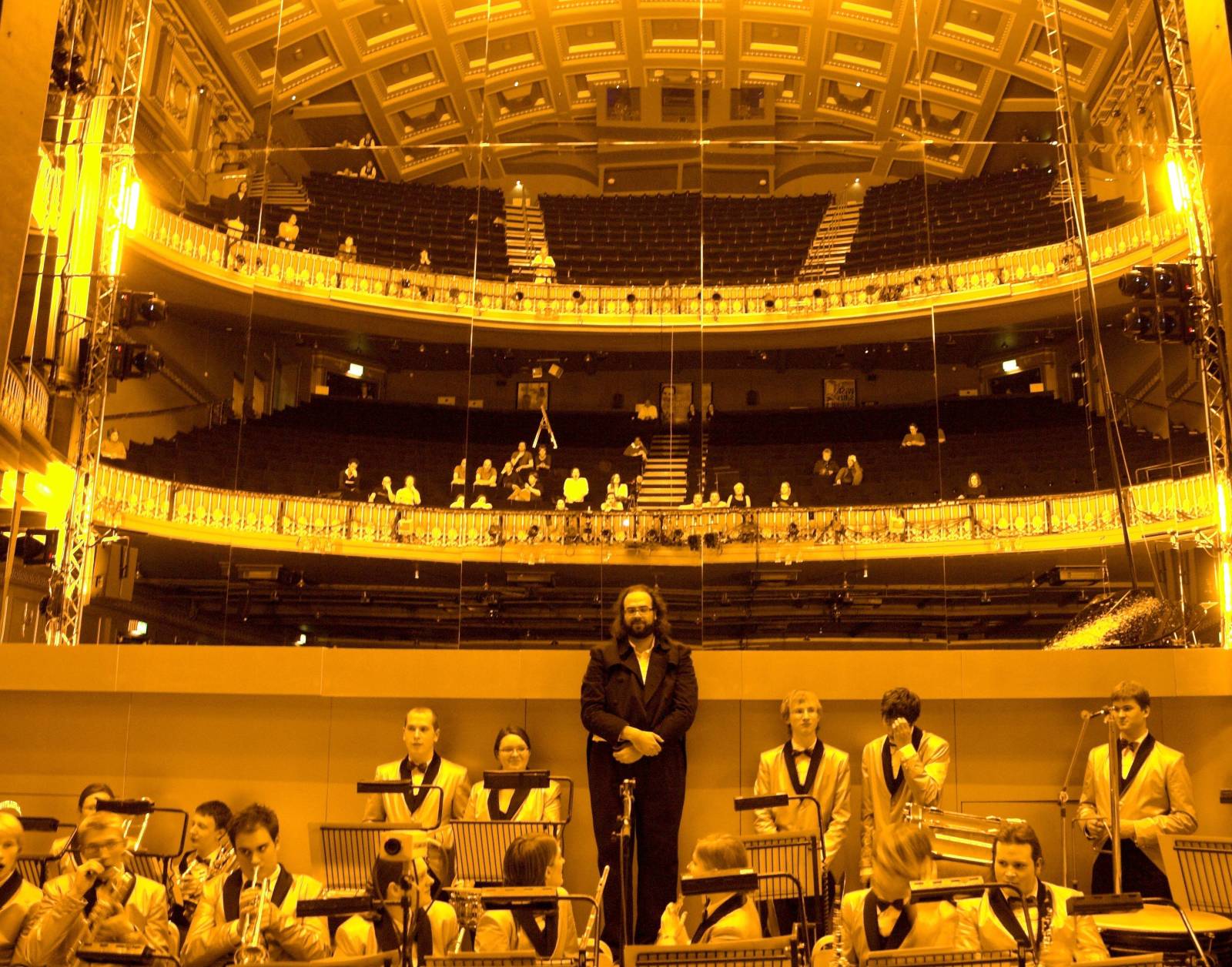

This week’s film screening features Ari Benjamin Meyers’ Four Liverpool Musicians (Bette, Budgie, Ken, Louisa), conceived on the occasion of the 2018 Liverpool Biennial. The film connects the subjects' personal histories and Liverpool's musical history, representing its major musical movements while at the same time relating back to the city's industrial past. This is the artist's first film-based work. It is 52 minutes long. Please note that headphones are recommended to appreciate the full range of the audio and musical performances.

The four musicians portrayed in the work of Meyers are closely tied to the history of Liverpool’s music scene:

Bette Bright was a singer for the legendary art rock band Deaf School. After Deaf School disbanded, Bright went solo with her backing band, The Illuminations. Journalist and author Paul Du Noyer once said of them: “In the whole history of Liverpool music two bands matter most, one is The Beatles and the other is Deaf School.”

Peter Edward Clarke, known professionally as Budgie, is an English drummer. While living in Liverpool, he co-founded The Spitfire Boys and Big In Japan. He then became the drummer of the Slits in 1979 and later the band Siouxsie and the Banshees (1979–96) and the drum-and- voice duo the Creatures (1981–2004). In 2013, Spin rated him at No. 28 in their list of “The 100 Greatest Drummers of Alternative Music”. Currently he performs with John Grant and Coco Rosie among others.

Ken Owen is an English drummer. He is best known as one of the founding members of Carcass, one of the early pioneers of the death metal genre. He is often credited as having invented the blast beat. In February 1999, he suffered a major brain hemorrhage and spent ten months in a hospital slowly emerging from a coma, making it impossible at the time for him to continue playing drums.

Louisa Roach is the songwriter and lead singer of the Liverpool based band She Drew the Gun. They won the Glastonbury Festival Emerging Talent competition in 2016. Their music has been described as psych pop and is known for its often political lyrics. They are currently on their first major headlining tour.

In his summary from the recent artist book by Ari Benjamin Meyers, Tacet in Concert, art historian Jörn Schafaff wrote:

"A filmic musical portrait of four musicians: two drummers and two singers coming from or having close musical ties to Liverpool: Bette Bright (Deaf School), Budgie (Siouxsie and the Banshees, Big in Japan), Ken Owen (Carcass), and Louisa Roach (She Drew The Gun). For each of them, Meyers wrote a composition specific to their musical background and current musical practice. They were then filmed performing the scores on the empty stage of Liverpools, Playhouse Theatre, the exact same place where the video installation was installed during the exhibition. Additionally, the musicians were filmed listening through headphones in silence to the playback of their own performance, which were all done in single takes. The three-channel film shows the four performances and silences together in varying degrees of overlap, thus creating a filmic meta-composition. With the film running in a loop, the visitors entered the darkened auditorium, invited to freely take a seat or move about the space." |

|

|

| K Club, 2019, performance protocol and right to re-stage, neon sign, 2 12-inch LP vinyl records, duration variable Exhibition view: In Concert, OGR Torino, Turin, 2019 Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

A band that is contractually obligated to disband once they have rehearsed sufficiently to perform. An orchestra that is pulled apart: each member isolated in a different room of a museum. A club that can be visited only alone. A conductor without orchestra but an audience “listening” as he conducts an undisclosed score. A duet between strangers.

To the titular figures of well-known literary works that have become idiomatic representatives of isolation—Alan Sillitoe’s long-distance runner and Peter Handke’s goalkeeper—one must add the artist: Only they can articulate their specific vision—either by giving it form themselves or by finding a way to communicate to others how this can be done. Even, or especially, in an orchestra, where a score gives a semblance of structure, each musician is alone. The conductor, its ostensible guide, is its most visibly isolated member.

Perhaps it is this realization and the experience of this position that precipitated a theme of individual responsibility and societal fragmentation that runs through some of Meyers work. It is a melancholy state, yet in works such as The Art or projects such as the Kunsthalle for Music there is the promise of solace, at least in a temporary union. Even The Lightning and its Flash (Solo for Conductor) operates on the premise that there can be a shared experience between the conductor and the members of the audience, if ever so momentary. In this it also demonstrates a fundamental truth about music and experience as such: They are, as the artist puts it in his script for Duet, “an ongoing series of fleeting moments mediated by a set of instructions”—not the worst description of life.

—Isabelle Moffat

|

|

|

A Portrait of Ari Benjamin Meyers — Alexander Abdelilah

|

|

| Ari Benjamin Meyers. Photo © Ricard Spiegel | |

|

As a way of introduction to the launch of our Online Viewing Room dedicated to Ari Benjamin Meyers, we reprint excerpts from Alexander Abdelilah’s essay on the artist from 2017. Written on occasion of the Ari Benjamin Meyers’ second solo presentation at the gallery, Solo for Ayumi, it presents an engaging portrait and summarizes the developments that led up the founding of the Kunsthalle for Music, a project which since the time of writing has developed significantly. After a first fully-fledged and public activation of the project, organized by Witte de With from January 25 to March 3, 2018, in 2019 the Kunsthalle for Music travelled to the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, CA, and the VAC Foundation, Moscow and was scheduled to open at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art this Spring to coincide with a presentation of his work Forecast at the Volksbühne and Berlin’s Gallery Weekend. |

|

|

Portrait of Ari Benjamin Meyers

by Alexander Abdelilah

A variegated orchestra of keyboards fills Ari Benjamin Meyers’ “non-professional recording studio,” as he puts it, a small room in his Berlin studio, located in one of the less hipster areas of the colorful Kreuzberg. Like a tour guide, the trained conductor and music addict introduces his keyboards like old friends at a party: “this one over here is a vintage Stevie Wonder-Supertramp kind of keyboard, this is a vintage drum machine from East Germany and I’d like to install another one here, a portable one I still have in the basement, very colorful, that looks like a spaceship.” On one of them, an old wooden Gerland, a live vinyl album of Kiss has the seat of honor, like a subliminal message intended for the conservatives and lovers of classical music, which Ari studied and then emancipated from: expect surprises.

If Ari Benjamin Meyers’ star is now shining bright in the world of contemporary art, critics are still struggling to define his art form: music gone wild? Art gone musical? A bit of both? Trying to answer that question leads to the elephant in another room: a beautiful vintage Grotrian Steinweg grand piano anno 1908, which massive wooden presence seems to dominate the entire place. A gift from a former conducting student who had inherited it from her grandmother: “she wanted to get rid of it, so she gave it to me in exchange for free lessons for life,” remembers Ari while gently sweeping dust residue off the keyboard with his right hand. After 6 months of lessons, his former student gave up. But Ari got to keep the precious piece. He still plays it, “even if it can’t be perfectly tuned anymore,” like an old school friend you don’t want to part ways with, even if he’s not the cool kid he used to be anymore. After a short pause, he confesses: “I’m still very much a composer.” |

|

|

| Ari Benjamin Meyers, Il Tempo del Postino, Manchester International Festival, 2007

Photo © Howard Barlow

| |

|

Composing is what led Ari Benjamin Meyers to Germany. Although he has been living and working in Berlin since the end of the 1990s, his relationship to this country started long before, in Bavaria. When he was 19, one of his conducting teachers, “an old-world guy in his eighties,” gave him a sealed letter with a mysterious instruction: get this letter to the chief conductor of the Bavarian Opera and he will take you on as an assistant. After having crossed the ocean, the young and naive music student had to jump over his first hurdle: without proper introduction in this elitist world and no knowledge of the German language, he was repeatedly sent away from the Munich Opera. He eventually came across the maestro himself and handed him the letter. Five minutes later, he was offered a job. A fascinating peek into a magical world where classical music is considered sacred.

After his summer internship, at only 19, Ari took the first of many unorthodox decisions that would shape his career: he declines a permanent job offer from the Munich Opera and decides to go back to the United States to study at Yale, proof that long before becoming an evasive subject for art critics, Ari Benjamin Meyers already was an outsider. During his time as a high school student at The Juilliard School, he had a side project absolutely no one there could know of. “This was before it became hip for a composer to have a rock band. I would have gotten in real trouble if my professors knew,” he tells us. When he then later came to Berlin on a Fulbright scholarship, in 1996, Ari experienced another cultural shock: he discovered a very institutionalized music world, students living lives of future state workers, far from the existential fear and the “let’s do it ourselves” spirit that was driving him back in New York City. “I wanted to do an opera or a concert in my living room, and they all wanted to know how much I was paying!” describes Ari Benjamin Meyers, laughing and shaking his head in dismay.

Wanting to step out of his comfort zone, he took a chance and dove into the experimental scene that was booming in Berlin at the turn of the millennium. “We rehearsed in lobbies of brand new but empty office buildings,” he remembers, “it was very exciting.” But once again, he felt let down by a world not nearly as experimental as he expected it to be. To quench his thirst for creativity and underground experiments, he played keyboard in an industrial band, and went farther off-road in 2004, throwing “Club Redux” club nights in some of Berlin’s best venues. “At that time we were among the first ones to bring in live contemporary music and performance next to DJs,” he insists proudly. |

|

|

| Jonathan Bepler, Untitled, 2018. Exhibition view: Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2018. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

A few years later, in 2007, he gets to direct musically a group show that will put him on the art world’s map. He takes part in the collective exhibition Il Tempo del Postino, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Philippe Parreno. A key moment in Ari’s opinion: “It was a sort of art school for me, to spend a year working with all these great artists.” Like the jesters in the opening performance of Il Tempo del Postino, Ari Benjamin Meyers seems to have had inverted vision glasses on in every role he tried to fit into, thinking and acting unlike most of his comrades of the music world, testing boundaries, going against what was expected of him. With contemporary art, he seems to have finally found a milieu in which he is at peace with himself, happy with that paradigm shift. “But it’s still a challenge,” he points out Finding a way to propagate his approach of music and art and inspiring others has been on Ari Benjamin Meyers’ mind for years.

The creative freedom of his new position gave him the opportunity and the means to invent a structure that will do just that: founded in 2016, the Kunsthalle for Music became the operational arm of this idealistic quest. The institution’s goal is to constitute an ensemble of like-minded artists who share their love for the connections and frictions between music and contemporary art. A symposium took place in late May 2017, ahead of the official opening in January 2018, but the ensemble is yet to be cast. “I’m looking for musical performers”, he explains, adding that the call is open to musicians but also thinkers, composers and dancers, as long as they have “some musical background”, to be sure they all speak that common language. Once it will be in place, this group of multitalented artists will be the heart of the Kunsthalle for Music, interpreting pieces composed for them by various artists. “The ensemble becomes a central curatorial frame of the Kunsthalle,” the founder explains.

|

|

|

| Yoko Ono, Sky Piece to Jesus Christ, 1965/2017. Exhibition view: Kunsthalle for Music, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2018. Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

| Click the image to listen (in German)

| |

|

Liu Ye in conversation with Alexandra Grimmer

|

|

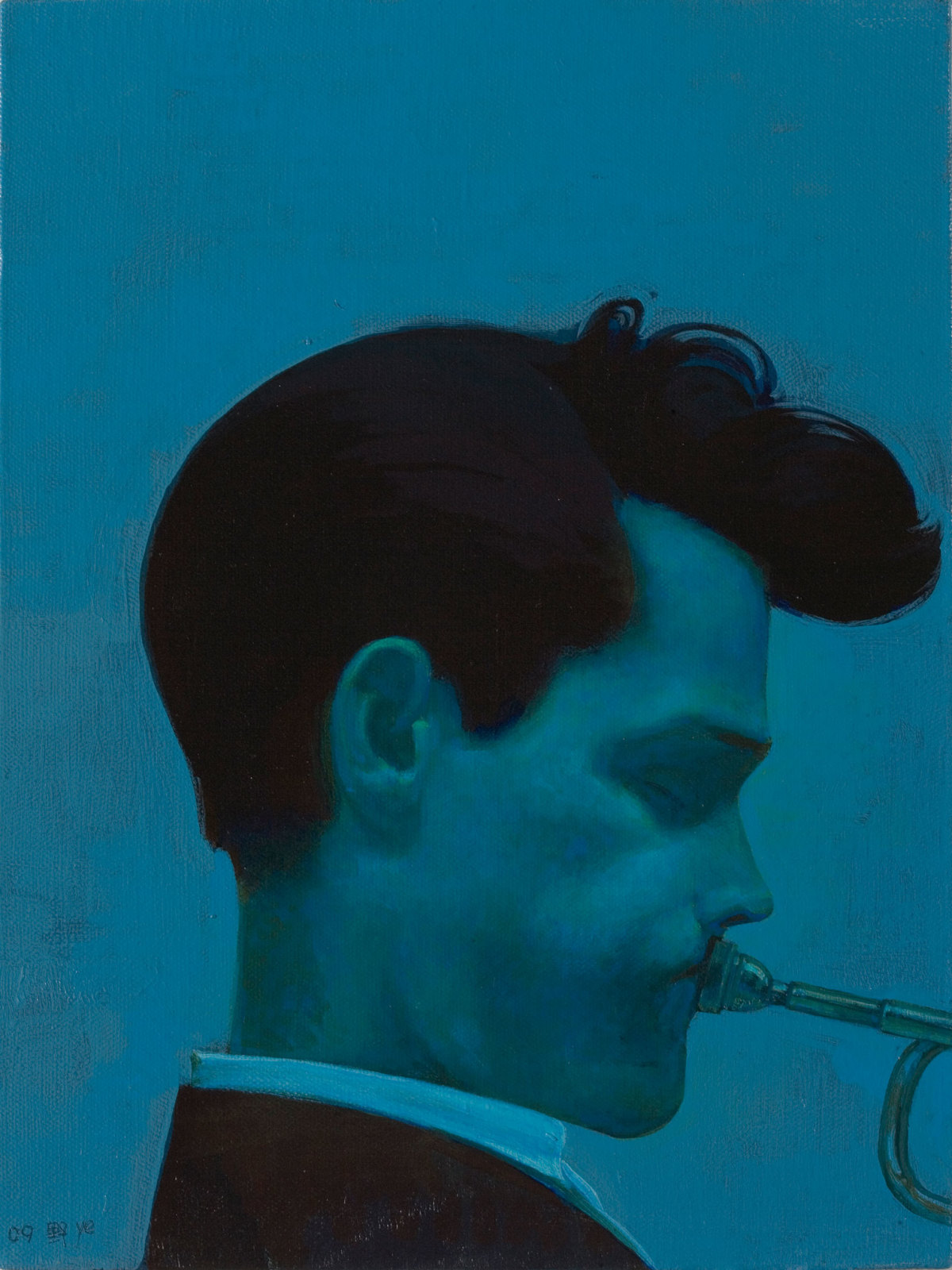

| Liu Ye, Chet Baker, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 40 x 30 cm

Private Collection, Beijing | |

|

Liu Ye’s work is often associated with his love of books: Images of specific books appear frequently in the artist’s work, at times filling the entire picture plane. Other paintings refer obliquely to literature: figures are seen to read or to draw, among them his recurring protagonist of Miffy, himself a character from a book. Less know is the artist’s love of music.

In Fall 2019 the Vienna-based curator Alexandra Grimmer interviewed Liu Ye. Over the course of two visits, they spoke about the artist’s studio, his working methods, the importance of narrative, and of course Mondrian. But the interview began with a long discussion of the role of music.

Below excerpts from their conversation which was just published in the May/June issue of Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art.

|

|

|

Alexandra Grimmer

Extended Moments and their Variations: A Conversation with Liu Ye

Alexandra Grimmer: You mentioned that you listen to all kinds of music in your studio. For example, when you worked on the big bamboo painting … in 2012, you listened to Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier.” You said that you imagined the forms of bamboo being similar to a Gothic church. I remember this sentence in the video documentation for that exhibition: “Actually I am thinking of Bach, I am not thinking of bamboo.” Could you tell me what impact Bach’s music has on you?

Liu Ye: Bach is timeless; I can listen to his music at any time, and every genre of his compositions—the cantatas, church music, or piano compositions. I usually put on Bach at least once a day. I like his music because it is so open to interpretation. It has a strong structure—music that is like mathematics—but, at the same time, it is very abstract music for me.

Bach is very different from Ludwig van Beethoven, for example, whose music does not work in the same way at all. For me, it is impossible to listen to Beethoven while working. Surprisingly, Dimitri Shostakovich also works well for me. Notwithstanding that Shostakovich’s music is very dramatic and very much loaded with action, my paintings are very much under control and silent. So, the influence can be rather contrary to my sensibility. Actually, I don’t understand it myself, but Shostakovich’s music still works for me while painting. As I said, Bach works at any time, and Shostakovich can be played under special circumstances—when I am in a special mood, usually in the afternoon, then it fits well with my work, but not in the morning and not at night. From Shostakovich, I prefer his Symphony No. 4.

|

|

|

| Liu Ye, Composition with Bamboo No. 4, 2011, acrylic on canvas, 50 x 70 cm | |

|

Alexandra Grimmer: Through the audio system upstairs in your working room, I can hear Massive Attack’s Blue Lines album playing.

Liu Ye: Really? Oh yes, I must have forgotten to turn off the player on my phone. Of course, one cannot only listen to Bach! But my taste in other music changes; for example, one month it is Björk and another month something else. At the end of the 1990s, I listened to a lot of Massive Attack’s music, then I forgot about it for many years.

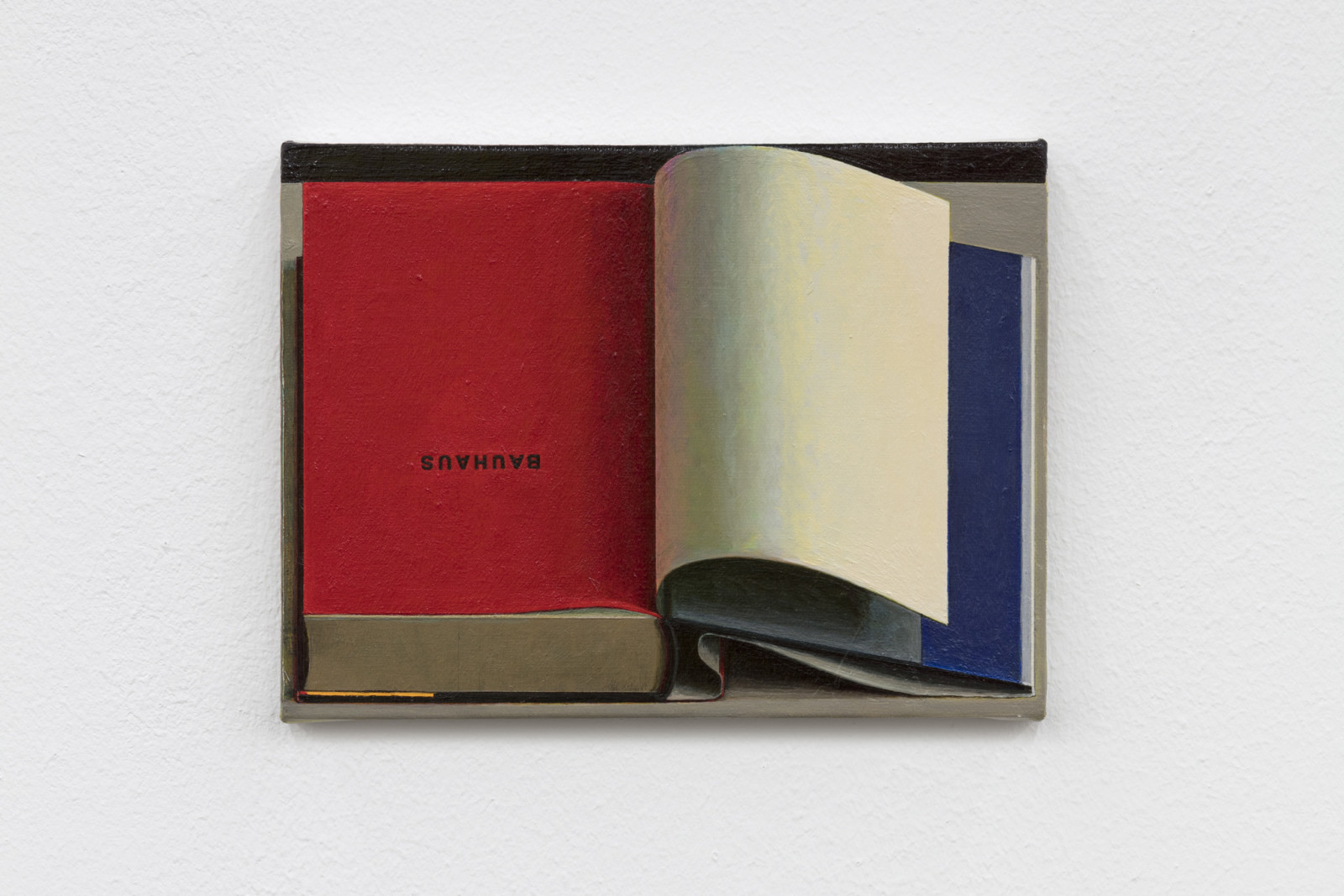

In my work I often use titles from music; for example, a version of Killing Me Softly came from the famous Fugees song of the 90s. Also, I’m a Soldier refers to the first song on Bjork’s album Post from 1994. Leave Me in the Dark was originally also from a song, but I forget by whom. I just liked this line in the song. In my recent works I don’t need to make a title very clear. It can be an abstract title. For example, in Book Painting No. 1 (2013), which is, for example like a Symphony No. 1, I copy the meaning, and it becomes something like a label. It can be No. 1 or No. 2. . . .

Alexandra Grimmer: So, you prefer to explain less?

Liu Ye: Yes, I don’t think it is necessary to explain too many things. I prefer to keep the painting’s meaning more open, which then makes it more abstract at the same time.

[…]

Liu Ye: What I meant [in another interview] by “self- portrait” is not really my self- portrait in that sense. It is more my world. Art or painting in relationship with the real world is false. In my world, the reality is following the art world. It is my total freedom to configure this world because it is purely mine. It does not have anything to do with whether I live in Berlin or in Beijing; for example, it is completely the same, since the outside context scene does not have much importance. When I leave the house in the morning, it does not give me an impression of where exactly I am. This is not of great importance as I live in my own world, which does not depend on the daily environment.

My world is based on culture—literature, film, or music. It is an art world—a parallel, artificial world. It has been like that since I can remember. When I was a child, I read all the tales by Hans Christian Andersen. This was during the period of the Cultural Revolution in which I spent much time reading, virtually living in Andersen’s world and not in the reality that was unfolding in Beijing at that time. Somehow I must have pronounced his name with a Chinese sound, and I was surprised when I learned that Hans Christian Andersen and his tales came from Denmark. The world in which “Thumbelina,” “Little Mermaid,” and “The Little Match Seller” took place felt like my world, and I therefore thought these were Chinese stories.

|

|

|

| Liu Ye, Bauhaus No. 5, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 15 x 20 cm

Friedrich Christian Flick Collection | |

|

Liu Ye: Again, when it comes to my artwork, I live in an artificial world, in my own art world, which is very rich and multi-layered. When I say that the art world is very rich, this has nothing to do with what physically occurs around the work of artists and exhibitions. The art world I am reflecting has nothing to do with people’s social circles. For example, regarding openings or parties, I go to very few, but I have many good friends. My inspiration comes from the second reality, my “secondary world.” It is not the direct reality. Of course, I know what is currently taking place in China or in Hong Kong; I know it very well, but there is no reflection of this in my art. There is no relationship between that reality and my work. They are two different worlds. Think of Mondrian, for example. His life was during the First and Second World Wars, but you cannot see it in his paintings. He had an art world that was very independent from his reality. With Otto Dix, on the other hand, you can see his time living in Germany during the 1940s reflected in his work. He is a great realist; you can feel the 40s in his art, but Mondrian is totally different. Alexandra Grimmer: But in Mondrian’s work, it is not possible to interpret any surrealism, just as an example. What makes your work different is that there are many more ways to interpret it. Liu Ye: I love Mondrian, but I’m not an abstract painter in the formal or traditional sense. I don’t follow his theory. He built up his work from realism to an abstract language. However, his art theory is not relevant for me. Moreover, I cannot love only the work of Mondrian. There are too many other influences for me. René Magritte, for example, is also very important, or even Marcel Duchamp—I enjoy reading his books. Sometimes when I am very tired, I read some lines of his writing and they give me a feeling of celebration and liberation. In my work, it may happen that I go down a dead-end street, but when reading some words by Duchamp, it is possible to relax again. There are so many types of art. From my understanding, all directions are equally important. Abstract art, for example, is not better than cartoon or comic art. I do sometimes enjoy reading comics, so for me there are also no categories of high-class or low-class art. The full interview is available in the May/June 2020 issue of Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art which is available in print and online HERE

|

|

|

| Exhibition views: Liu Ye, Storytelling, Fondazione Prada, Milan, 2020

Photos © Roberto Marossi | |

|

On Tuesday, his birthday, Ryan Gander hosted a special DJ-ing session on the live radio streaming station Radio_Caroline. You can spend some time with Ryan and his two daughters as he puts on records and chats. It’s charming!

|

|

|

The Reading Corner – A Selection of Publications

|

|

Ari Benjamin Meyers

Tacet in Concert

Publisher: Corraini Edizioni

Language: English

Available here

The first artist's book by Ari Benjamin Meyers, Tacet in Concert is conceived as the final chapter of a three-part project, and completes the journey begun with his two solo exhibitions: Tacet and In Concert. Very different in content and presentation, the two shows were held almost consecutively during 2019, the first at Kasseler Kunstverein and the other at OGR Turin. |

|

|

Liu Ye

Catalogue Raisonné 1991-2015

Publisher: UCCA / Hatje Cantz

Language: English / Chinese

Available here

This first catalogue raisonné featuring the works by Liu Ye provides an overview of his creative output from 1991 to 2015 |

|

|

Beethoven Moves

The 250 anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birth was supposed to be a year of concerts. A broadly conceived group exhibition at the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien examining the lasting influence of the composer’s work, of his life and of the reception of the figure “Beethoven” has also been postponed (to September 2020). This fascinating catalogue gives an idea of the rich web of associations (and many unexpected connections) across all media and many historical epochs that the organizers assembled.

PARTICIPATING ARTISTS

John Baldessari, Jan Cossiers, Ayşe Erkmen, Caspar David Friedrich, Francisco de Goya, Rebecca Horn, Idris Khan, Anselm Kiefer, Auguste Rodin, Tino Sehgal, J.M.W. Turner, Jorinde Voigt, Guido van der Werve

|

|

|

Viaggi da Camera with Francesco Gennari

|

|

| Photo © Francesco Gennari / Fondazione Nicola Trussardi | |

|

VIAGGI DA CAMERA is the new online project from the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi. "Viaggi da camera" collects and distributes daily images, videos and texts, chosen by artists invited to show their home and private space.

Every day a new contribution will be published on the Foundation's website and social channels. Inspired by Xavier de Maistre's famous 18th century novel "Journey around my room" - written during a 42-day obligatory stay in a room in Turin - "Viaggi da camera" invites artists to open the doors of their real and imaginary rooms. Taken from day #39, Francesco Gennari shared a glimpse into his home life in the midst of lockdown. |

|

|

|

|