Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version unseres Briefes aus Berlin!Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! This week we continue to focus on new projects and re-opening exhibitions. This week we take the exhibition of several major works of Anri Sala’s (at ARoS, in Aarhus, the Kienzle Art Foundation in Berlin, and at the gallery) as occasion to focus on the artist and also screen his Take Over (Marseillaise) as our weekly online film. As part of Festival! Isa Melsheimer and N.Dash’s exhibition continues through next Thursday. The following weekend, July 11th, Sala’s exhibition with Saâdane Afif will open. We want to draw your attention to a comprehensive exhibition by Grönlund-Nisunen at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum and reprint from an interview and an essay on the two Finnish artists. And beginning July 14th, Simon Fujiwara will exhibit Joanne as part of the 2020 Seoul Photo Festival. Details can be found below. The weekly Letter from Berlin will break for summer! After a travel issue in late July, we will return with new stories in the fall. All past issues and anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our digital platform. Read this in good health.

|

|

|

Film screening Anri Sala, Take Over (Marseillaise)

|

|

| Anri Sala, Take Over (Marseillaise), 2017, HD video projection, color, stereo sound, duration 7:56 min

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Film still © the artist

| |

|

This week Anri Sala’s large-scale sound and video installation Take Over opens as part of Mythologies – The Beginning and End of Civilizations at ARoS Museum of Art in Aarhus. In Berlin the artist’s early masterpiece Intervista will be on view at the Kienzle Art Foundation, and the following weekend, on July 11, the third Festival! exhibit will pair Sala with his long-time friend Saâdane Afif. We take this as occasion to screen Take Over (Marseillaise)—one of the two films that make up the tightly choreographed interaction of image and sound in the installation—and to take a closer look at the artist’s work currently exhibited in the gallery, If and Only If (modern times) from 2018.

Take Over (Marseillaise), 2017

An encounter with a familiar tune usually produces a curious pleasure that rises from our anticipation of what will follow. Take Over eludes gratification, as it willfully entangles two globally celebrated songs—La Marseillaise and The Internationale.

Written and composed in 1792, La Marseillaise was originally tied to the French Revolution, before it spread to other countries where it became a symbol for the overthrow of oppressive regimes. The 1871 lyrics of The Internationale—a hymn to the ideals of fairness, equality and solidarity—were initially set to the tune of La Marseillaise, until its original music was composed in 1888. This musical kinship reveals their one-time symbolic affinity. From the onset, both anthems have undergone major changes in their political connotations: from revolution, restoration, socialism, resistance and patriotism, to additional associations with colonization and oppression in the second half of the twentieth century (as the national anthems of France and the Soviet Union respectively). Yet to this day their meaning remains in flux, as the two songs continue to be appropriated.

A lively performance between a pianist and a self-playing piano pits the two anthems against each other, transforming the keyboard into an animated landscape of valleys and peaks. The conjunction of the two melodies produces an estrangement that is not caused by the intrusion of the known by the unknown, but the subversion of the known by an equally well-known tune.

—Anri Sala

|

|

|

| Anri Sala, Take Over, 2017, back-to-back HD video projections, color, 8-channel sound, glass elements

Duration 7:56 min, dimensions 258 x 873 x 873 cm

Exhibition view: Anri Sala, Take Over, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2017

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

Mythologies – The Beginning and End of Civilizations is a wide-ranging exhibition tracing the power of narrative constructions through several centuries. As the organizers put it, the exhibition will uncover periods where old narratives are discarded and new ones emerge, often via radical ruptures. In this way, the exhibition bridges the past and the present while also shining a light on social changes that have changed the emphasis on those mythologies and narratives that have been cardinal to sustaining social constructions. At ARoS Take Over is seen in its initial configuration at the gallery in Berlin: as a contained architectural structure consisting of a central wall with angled glass panels. A conceptual point of departure for Take Over are two well-known musical works, affiliated by an entangled political and cultural history, the Marseillaise and the Internationale. Written in 1792 the Marseillaise was closely tied to the French Revolution but also quickly spread to other countries where it became a symbol for the overthrow of oppressive regimes. Thus the 1871 lyrics of the Internationale were initially also set to the tune of the Marseillaise, until 1888 when its original music was composed and the song became the standard anthem of the socialist movement. Both anthems have undergone major changes in their political connotations: from revolution, restoration, socialism, resistance and patriotism, to additional associations with colonization and oppression in the second half of the twentieth century (as national anthems of France and the Soviet Union, respectively). Yet to this day their meaning remains in flux, as the two songs continue to be appropriated. Take Over makes audible the close relationship of these two political anthems and mines the musical kinship for traces of this changing symbolic significance. The two songs appear doubled in two complementary films. Each projected on one side of the projection wall, the films depict the keyboard of a Disklavier piano, played by a human player and animated by its programming. A variety of actions—rhythmic movements, single strokes, clusters, waves or bursts, transforms the keyboard into an animated landscape in black and white. Around the central screen, the large glass panels create specific acoustic environments in which only specific parts of the soundtrack are audible. In a spatial equivalent of the two choreographies of music and image that structures the two films, these sections further arrange the auditory experience created by the installation. Take Over seamlessly dissolves the boundaries between individual media—the films are sculptural, the glass walls cinematic and the oscillating sounds appear to mold the space. Moreover, sound literally determines the film, whose changing focus is tied to musical tones and the movement of the keys producing them—even if the underlying system remains elusive. The work has been presented in different configurations, as part of the artist’s solo exhibitions at Museo Tamayo, Mexico City, 2018, Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2019, MUDAM – Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art, Luxembourg, 2019, and at Centro Botin in Santander, 2020. Further information on Mythologies – The Beginning and End of Civilizations can be HERE.

|

|

|

| Anri Sala, If and Only If (modern times), 2018, film still milled on wooden textile printing stamp

6 x 27,5 x 37,5 cm (2 3/8 x 10 5/8 x 14 5/8 in) (sculpture)

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Photo © Roman März | |

|

Currently on view as part of PS81E at the gallery, Anri Sala's work If and Only If (modern times) is a vintage textile printing stamp with a motif etched on its surface, presented on a plinth. The carved image depicts a snail on a viola bow. It refers to the artist’s 2018 film If and Only If in which a snail travels the full length of a bow, altering the performance of the renowned violist Gérard Caussé playing Igor Stravinsky’s Elegy for Solo Viola. The performance becomes both an interactive improvisation and an exchange between the musician and the animal. As the snail moves forward or slows down, the performer responds accordingly. As a result, the original score is reinterpreted, and the composition’s duration gets extended.

Sala’s wooden sculpture expands on time, its passing and units of measurement. While in the film the tempo of Stravinsky’s Elegy is contrasted with the speed of the snail, the wooden stamp engraving creates a fossil of a film still, materializing a single frame of the ephemeral moving image.

For more information visit our PS81E Online Viewing Room.

|

|

|

| Exhibition view: PS81E, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2020

Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

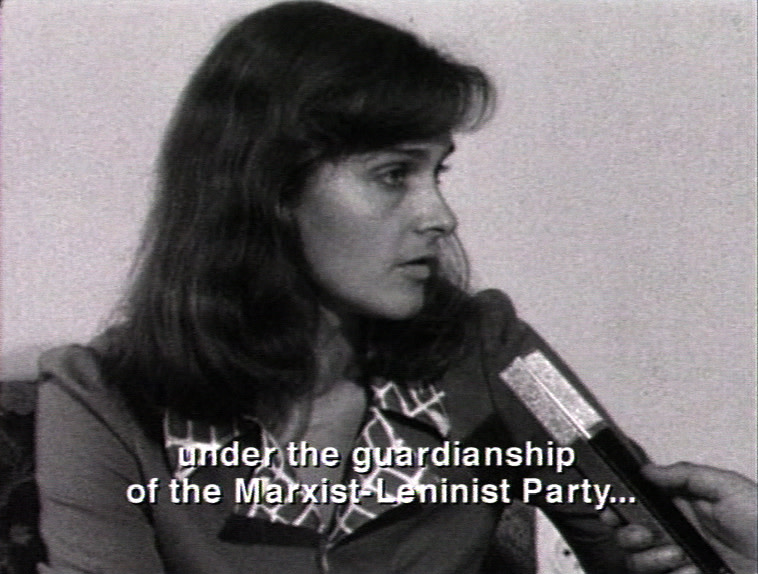

| Anri Sala, Intervista, 1998, single-channel video and stereo sound, duration: 26:00 min

Courtesy the artist; Idéale Audience International, Paris; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich; Esther Schipper, Berlin

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Film still © Anri Sala

| |

|

Kienzle Art Foundation On SpeakingJuly 4, 2020 - August 22, 2020 Opening July 4, 2020, 3 – 8 pm Julia Büse, Jeremy Deller, Hell Gette, David Lamelas, Julika Rudelius, Anri Salacurated by Julia Eichler The group exhibition features the 1998 Intervista, made while Anri Sala was still a student in Paris. After finding silent 16mm footage of a speech his mother gave in the late 1970s—as a young woman she had been one of the leaders of the Albanian Communist Youth Alliance—the artist had students from a school for the deaf lip-read from the film to reconstruct the speech. Sala then confronted his mother with the film and text. She was astonished not by the content, as Sala later said, but by the syntax of her speech at the time. Further information can be found HERE.

|

|

|

PS81E Online Viewing Room

|

|

Festival! #2 – Isa Melsheimer | N.Dash

|

|

| Exhibition view: Festival! A Project by Esther Schipper and Mehdi Chouakri, Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin, 2020

Photo © Ludger Paffrath

| |

|

Festival! A Project by Esther Schipper and Mehdi ChouakriMehdi Chouakri, Mommsenstrasse 410623 Berlin Isa Melsheimer | N. Dash June 27 - July 9, 2020 Press Release DEPress Release EN

|

|

|

Grönlund-Nisunen Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai |

|

| Grönlund-Nisunen, High Frequency, 2020, parabolic aluminium reflectors, aluminium stands, Geiger counter, control unit, amplifier, high frequency drivers, 28,5 x 2, 3 x,1,9 m

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

Two parabolic reflectors, each with a high frequency driver at its focal point, stand facing each other at opposite ends of the exhibition space. The high-pitched sine-wave tones played through the drivers form a sound axis between the mirrors. The pitch of the sound from one speaker is steady, while the pitch from the other changes in response to impulses from a Geiger counter measuring random changes in the background radiation. The sounds mingle together to create a lower interference tone, which appears to come from everywhere.

| |

|

On July 17th, 2020 Tommi Grönlund and Petteri Nisunen's major solo presentation will open at the Minsheng Art Museum in Shanghai and continue through the end of November. Delayed by the recent closures, the exhibition occupies the entire museum's 2,500-square-meter exhibition space on two floors and features more than twenty works, mainly large-scale installations using kinetics, light and sound. The selection of works spans the artists entire career, including new site-specific works created specifically for the museum space. By way of introduction we reprint an interview conducted with Tommi Grönlund and Petteri Nisunen and continued with excerpts from John Peter Nilsson's essay on the work of the two artists. The text first appeared in Grönlund Nisunen, Grey Area published on occasion of their 2017 solo exhibition at Taidehalli Helsinki.

|

|

|

1. Where and when did your joint artistic work start?

We held our first joint exhibition at the Titanik Gallery, Turku in 1993. However, we had already worked together on various architectural and art projects and competitions before that. We got to know each other while studying at the Department of Architecture at Tampere University of Technology in the late 1980´s and early 1990´s. At the end of our studies, we acquired a study in Helsinki and later founded a.men architects Ltd. with our three fellow students. We were interested in various projects moving between art, architecture and design, and we gradually drifted from the work of an architect to that of an artist.

2. Why are you interested in space, movement, sound and light?

Probably above all because they are all key elements of architecture. We perceive space not only through sight but also through hearing and touching, and movement is also central element in perceiving a spatial experience.

In our works, the use of sound and light is often related to the perception of space, and movement brings a temporal element to the works. We are also interested in these matters purely as phenomena, and in some contexts we try to look at them as neutrally as possible, without any particular emphasis on the spatial aspect.

In addition to our collaborative practice, Tommi has his own relationship to sound, which he realizes by releasing music through his record label Sähkö Recordings.

3. What is the division of labor in the execution of works?

Our division of labor is quite chaotic and always varies according to the situation.

We make sketches together and separately and think of different options with the help of simple prototypes, etc. The final form of a work is often determined by what is possible in that particular situation and within the available budget.

Work will continue on making the necessary working drawings and finding suitable subcontractors. This has often been more of a matter of mine, while Tommi is more responsible for simultaneous hardware purchases, editing of audio files, etc. But even in this respect, the roles always vary according to the situation.

In the final stages of working, we run to various subcontractors negotiating details, etc.

Once the parts and technology of the work have been acquired / commissioned / done, testing of the work follows. Due to the scale of the works, this is often only possible in the exhibition space itself, leaving changes to the last minutes. Over time, we have already become accustomed to it. Because of the way we work, we often get to know technical staff as well as curators and museum directors when setting up exhibitions.

4. How do you solve / clarify issues related to the technical implementation of your works?

In the prototype phase, we considered various technical possibilities to implement what we are doing at any given time. At this stage, our technical assistant Jari Lehtinen has been, and often still is, actively involved. When we get an idea in our head, we often call him to ask if it can be implemented. His typical answer is that you should give it a try. Due to his long experience in the field, he sometimes tells us that someone else has done in technical sense almost similar work years ago, which usually means that we drop the idea.

In addition to him, we also use several other subcontractors. Over the years, we have learned to listen to the views of subcontractors on how it is best to realize a particular detail. Negotiations with them can lead to significant changes. When selecting subcontractors, it is essential that they are interested in the whole, not just in performing their own work as efficiently as possible.

|

|

|

| Grönlund-Nisunen, Orbita, 2005/2018, a stainless steel ball, stainless-steel rails, electric linear actuators, switches, a light bulb, electric cable, 7 x 7 x 0.5 m

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

A stainless-steel ball, 35 cm in diameter, moves slowly around a circular stainless-steel track. A single light bulb at the center of the circle casts a shadow of the moving ball onto the surrounding walls. The soundscape created by movement of the steel ball is very present in the space. The continuous movement of the ball is maintained by gravity and minimal friction. Three electric jacks at roughly equal distance apart pull the tracks together just after the ball has passed, lifting the ball a little, thus making it run downhill to where the tracks are wider.

| |

|

Transformations

By John Peter Nilsson

(….)

Initially, I had thought of casting Tommi Grönlund and Petteri Nisunen as some sort of technological mystics. Inherent in mysticism is a different understanding of reality from the one we live in, a conception with a definition that is not natural, but supernatural, and which can only be perceived as an “instinct”, “intuition”, “revelation”, or some form of “just knowing”. In her essay “Against Interpretation” from 1966 the author and debater Susan Sontag writes, for example, that an interpretation risks taking the sensory experience of an artwork for granted. “What is important now,” Sontag writes, “is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.”

But sensoriality does not necessarily have to be based on some mystical notion. There is also a rational, almost systematic, side to Grönlund and Nisunen’s artistic work. In 2001, they curated the exhibition The North is Protected in the Nordic pavilion at the Venice Biennale, in which they themselves took part, together with Leif Elggren, Carl Michael von Hausswolff and Anders Tomren. The whole thing was virtually a Gesamtkunstverk, discreet and minimal, yet foregrounding the architect Sverre Fehn’s distinctive building from 1962 (Grönlund and Nisunen both studied architecture) in a way that complemented it. |

|

|

| Grönlund-Nisunen, Pneumatic Landscape, 2004/2020, polyester fabric, chipboard, timber, fans, digital dimmer, computer, 24,4 11,0 x 3,5 m

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

The new site-specific version of the work for Minsheng Art Museum makes use and emphasizes the unique nature of its main exhibition hall. The pneumatic abstract terrain model, which slowly changes size and shape. Silent fans create air pressure that maintains the shape of the thin polyester fabric. A digital timer system regularly switches the fans off for several minutes, during which peaks of the landscape slowly collapses and loses about one third of its volume before filled up again.

| |

|

Grönlund and Nisunen’s work consisted of around three hundred steel wires stretched along one wall of the pavilion. The wires moved irregularly, creating a kind of optical illusion, as if the wall were in motion, too. Taken overall, it was evident that the four artists had worked closely together. Von Hausswolff and Elggren’s sampling of all the audible local fm radio stations, converted into sound frequencies in the space, could be the source of the movements of the wires. And if we looked through Tomren’s intermittently transparent panes of glass, the exhibition space became subtly distorted. The curators/artists Grönlund and Nisunen, together with von Hausswolff, Elggren and Tomren, not only succeeded in creating an integral impression, but also had the architectural context play a role in the experience.

Looking at Grönlund and Nisunen’s entire oeuvre, we see that they frequently return to the way that the context of the space is played off against various types of physicality. Moreover, many of the works have time as a common denominator. A process unfolds, created partly by interaction with visitors, partly by the works in themselves. Grönlund and Nisunen have, of course, worked in a succession of different materials and techniques over the more than thirty years that they have been active as artists. But, surprisingly often, this involves electricity, sound and light – in fact, a kind of poetry of electricity, sound and light.

|

|

|

| Grönlund-Nisunen, LED Horizon, 2020 (detail), blinking white LEDs, copper covered steel wire, stainless-steel wire, stainless-steel counterweights, stainless-steel structures, power sources, electric cord, 24,3 x 1,3 x 0,5 m

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

This site-specific installation is produced especially for the first-floor corridor space of Minsheng Art Museum. Two pairs of thin copper-covered steel wires are stretched between steel columns in both ends of the corridor. A line of blinking white LEDs is soldered to both pairs of copper covered steel wire, one minus and the other plus pole, and create two parallel lines of blinking lights.

| |

|

Grönlund and Nisunen’s artistic oeuvre stands in interesting relation to McLuhan’s account. Their interest in industrial material and technical solutions of various kinds is not a nostalgic longing for some machine age. Materials and technologies are liberated from their original purposes and used freely in new significances. But not in any mystical sense, as I initially mistakenly suspected. Rather, the works evoke subtle sensory states.

One classic claim is that good art sharpens the senses. In Grönlund and Nisunen’s case this is extra clear. We don’t see their works. We experience them. With all of our senses. But these works are deceptive. There is a whiff of industrial technology about their installations that can lead our thoughts to rational, explanatory interpretations. But I see them as using the technology to a contrary end. With electricity, sound and light as their cornerstones their installations create presence; I become extremely tangibly present when facing or when inside their works.

|

|

|

| Grönlund-Nisunen, Spring Field, 2012, coil springs, solenoids, brass wire, steel attachments, electric cable, control unit, power supply, dimensions 2,5 x 2,5 x 5,5 (foreground, right)

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

A total of 50 long coil springs are stretched vertically between floor and ceiling. On the floor next to each coil spring is a solenoid. A grid made of brass wire was stretched along the floor, in line with the grid of coil springs. The wires stretched in one direction have a positive charge, while those stretched at right angles to them have a negative charge. If there is a solenoid where the two wires cross, it is turned on and hits the coil spring, making it resonate. The springs continue to resonate for some time, keeping the whole installation vibrating. The sharp clicking sounds made by the solenoids produce a random, but clear rhythm.

| |

|

If we were to sum up Grönlund and Nisunen’s artistic work, we might perhaps best do so via phenomenology. They are fascinated by the realities of being, and curious about the everyday phenomena of existence. They make immaterial phenomena such as sound and light perceptible, at the same time as they reveal technological mechanisms in simple, solid ways that are clearly executed. Undoubtedly, I am profoundly fascinated by the way they have constructed their works. But I don’t see this as the main point of their art. In some magical fashion their constructions are transformed into subtle forms of the sensory that refine my own perception. Indeed, I quite simply see the world better with the aid of Tommi Grönlund and Petteri Nisunen’s art.

The full text can be found in Grönlund-Nisunen, Grey Area, 2017. See below for order information.

|

|

|

| Grönlund-Nusunen, Electromagnet Installation, 1997, sand-blasted steel sheets, stainless-steel rods, electromagnets, control unit, magnet driver units, infrared sensors, a power supply, dimensions variable

Exhibition view: Grönlund-Nisunen, Flow With Matter, Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, 2020

Photo © Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum

Eight sand-blasted steel sheets hang from the ceiling of the exhibition space. Electromagnets, stuck to the under surface of each steel sheet, are connected to an infrared sensor via a control unit. When a sensor detects a human presence, the control box begins rapidly switching the electric current to the magnet on and off , which makes the sheet resonate. The public’s movements cause the nine sheets – each one in a different phase – to create a constantly altering soundscape in the exhibition space.

| |

|

Simon Fujiwara 2020 Seoul Photo Festival, Seoul |

|

| Simon Fujiwara, Joanne, 2016/2018, three free-standing aluminium-clad structures:one with in-built LED monitors screening video(duration 12:06 min) and digital print, two lightboxes with digital prints on foil. Dimensions variable, duration 12:06 min (video), commissioned by FVU, The Photographers’ Gallery and Ishikawa Foundation, supported by Arts Council England.

Exhibition view: Simon Fujiwara, Joanne, ARKEN Museum of Modern Art, Ishøj, 2019

Photo © David Stjernholm | |

|

2020 Seoul Photo Festival UnPhotographical MomentSeMA, Buk Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul July 14 - August 16, 2020 Simon Fujiwara's Joanne is part of the 20th Seoul Photo Festival. The group exhibition opens at the Buk Seoul Museum of Art from July 14 to August 16th. With this year's theme, UnPhotographical Moment, the organisers seek to highlight works that explore the original meaning of a photography of the now and focus on what is an “everyday image” to us. Participating artists are Simon Fujiwara, Masashi Sanai, Stone Kim, Jeongnam Goh, Siyoung Jun, Heakyung Ham, Yeji Hwang, Minkyu Seo, Anna Fox, Walid Raad’s Atlas Group, Sophie Calle, and Catherine Opis. Further information can be found HERE (in Korean, the English page will be updated shortly) |

|

|

Anri Sala

Bendings: Four Variations on Anri SalaPeter Szendy, 2019

Publisher: Edition Mudam Luxembourg, Mousse Publishing

Language: English, French

Available here

|

|

|

Grönlund-Nisunen

Grey Area

Texts by Mikko Heikkinen, Petri Kuljuntausta, John Peter Nilsson, Edited by Pirkko Tuukkanen, 2017

Publisher: The Finnish Art Society

Language: English / Finnish / Swedish

Available here

|

|

|

|

|