Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version unseres Briefes aus Berlin!Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! This week we focus on the work of AA Bronson and General Idea in this Letter from Berlin. There is much to discover: a film, God is My Gigolo, two recent interviews the artist gave on the parallels of the health crises regarding AIDS and COVID19, past exhibitions, his ongoing project A Public Apology to Siksika Nation, presented in an excerpted essay by Ben Miller, and notes on the recurring motif of the poodle in General Idea’s oeuvre. Another highlight is AA Bronson’s powerful text I Love Berlin! The weekly film screening features General Idea’s God is my Gigolo from 1969-70. (Please note these weekly viewing links are temporary: The film is available to view only through Sunday night, Berlin time.) We also want to draw your attention to the opening of Karin Sander’s major solo exhibition at the Museion in Bolzano and to the online screening by the Berlin-based project space Scharaun of films by Anri Sala premiering today. Anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our digital platform. Read this in good health.

|

|

|

General Idea's God Is My Gigolo – This weekend’s online film screening |

|

| General Idea, God Is My Gigolo, 1969-70, film 16 mm, duration 34:40 min

Film still © The Estate of General Idea | |

|

General Idea’s first film, God is my Gigolo (1969-70), was shot in black and white on 16mm film without sound. It is in effect a documentary of the early years of General Idea – some of the scenes were shot in the neighborhood of the old Toronto house inhabited by the group of friends from which General Idea would form. All the participants of God is my Gigolo were involved with the beginning of General Idea and also the Miss General Idea pageants staged annually from 1968 and 1971: directed by Jorge Zontal, with Felix Partz, AA Bronson, Mimi Paige (the first Miss General Idea), Granada Gazelle (the second Miss General Idea), and Miss Honey (the third one).

Joined together as fragments, the footage includes slapstick elements, dance numbers and a mock-tropical idyll shot on a small island near Toronto: Honey and Granada play island maidens sporting coconut bras and shreds of fishnet, while Mimi acts the part of a naive young girl on the road to sexual discovery.

|

|

|

AA Bronson and General Idea |

|

| Photo © Piotr Perobski | |

|

AA Bronson co-founded the artists’ group General Idea with Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal in 1969.

Throughout its 25-year-long career, the Canadian group produced an important body of work in various media and formats, which continues to be a reference point for generations of artists around the world. Their works touch upon topics such as archaeology, history, sex, race, illness, and the myth of the group itself through self-portraits, a recurring subject of their production. General Idea began making AIDS-related works in 1987—they were pioneers in incorporating the issue of AIDS in art—and produced countless installations on this theme. The three artists worked and lived together until the deaths of Felix and Jorge in 1994.

Since then, Bronson has worked and exhibited as a solo artist, often collaborating with younger generations of artists. Since 1999, he has worked as a healer, an identity that he has also incorporated into his artwork. From 2004 to 2010, he was the Director of Printed Matter, Inc. in New York, founding the annual NY Art Book Fair in 2005. In 2009, he founded the Institute for Art, Religion, and Social Justice at Union Theological Seminary in New York. In 2013, he was the founding Director of Printed Matter‘s LA Art Book Fair. He has taught at the University of California in Los Angeles, the University of Toronto, and the Yale School of Art.

AA Bronson’s artistic practice has long included elements of shamanism, although this tendency became more apparent only after the deaths from AIDS in 1994 of his collaborators Zontal and Partz. At the same time, as Bronson acknowledged: “The 60s obsession with Eastern religions, states of the ecstatic, and theories of radical living and working fit me perfectly. General Idea never presented itself as spiritual, but behind our corporate mask, we were the product of our generation.”

Bronson’s best-known project is perhaps his series of performative healing rituals and séances, Invocation of Queer Spirits (2008–09), for which he collaborated with Toronto artist Peter Hobbs to stage spiritual experiences in five locations across North America; in Banff, Alberta, New Orleans, Louisiana, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Governor’s Island, New York, and Fire Island Pines, New York. Bronson has characterized this series of performances as “a hybrid between group therapy, ceremonial magic, a séance, a circle jerk, and a quilting bee.”

|

|

|

Catch me if you can! AA Bronson + General Idea, 1968–2018 |

|

| Exhibition views: Catch me if you can! AA Bronson + General Idea, 1968–2018, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2018

Photos © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

In 2018, the gallery presented Catch me if you can! AA Bronson + General Idea, 1968–2018, an exhibition that for the first time presented the work of AA Bronson and General as a continuum which was also emphasized by presenting the works chronologically according to a continuous timeline.

As its organizer Frederic Bonnet noted about the presentation: This system, while affirming a great conceptual coherence, continuities, nods, and cross-references, bears witness to the important formal diversity and to the intense creativity of artists who have never ceased to renew their vocabulary, even in regard to considerations spanning across half a century of work.

Organized with Sholem Krishtalka, under the name Krishtalka Books, the bookstore featured catalogs, rare books, editions, zines, and ephemera by AA Bronson and General Idea.

|

|

|

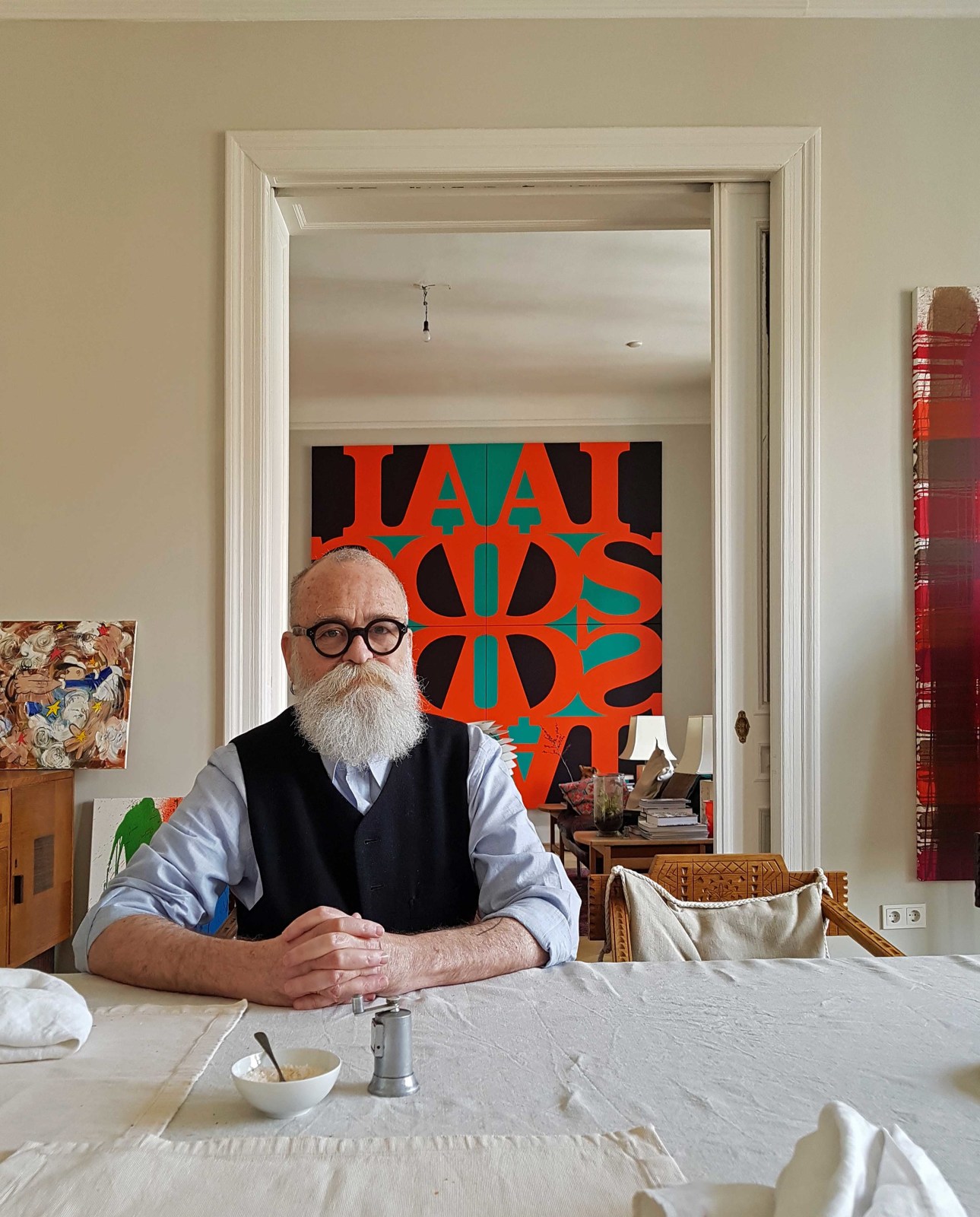

| AA Bronson in his Berlin apartment in 2020. Photo © Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur

| |

|

First conceived in 2017 for a panel at the Berlin-based book fair Miss Read, AA Bronson’s Love Letter to Berlin is loosely based on The Epistle to the Galatians by Paul the Apostle. It was performed in an expanded version by the author during the BMW i Art Talk “Why Berlin? – the Arts and the City” at Soho House Berlin in 2018. |

|

|

"Born Michael Tims in Vancouver, Canada, at dawn on June 16, 1946; at the age of seven I turned away from Christianity to explore other paths; in the 60s I was a hippy, I founded a commune, an underground newspaper, and a free school; I was a member of the artists’ group General Idea for 25 years; publisher of FILE Megazine for 18 years; a founder and Director of Art Metropole, Toronto from 1974; an AIDS activist during the war years of the 80s and 90s; a healer and a master of butt massage for fifteen years; for seven years Director of Printed Matter, New York; founder of the NY Art Book Fair in 2006; founder of the LA Art Book Fair in 2013; founder of the Institute for Art, Religion, and Social Justice; founder of AA Bronson’s School for Young Shamans."

To the artists, gallerists, musicians and writers who make Berlin what it is today; to the students gathered here today and especially to the students of art or of religion; a special hello to the hipster Jews from Israel and Montreal and Brooklyn; to the queer community; to the mad and disabled; to the refugees and immigrants and expats.

To the Turks and Russians and Poles and Syrians and Slavs and Arabs and Iranians; to those of color; and to all the marginalized communities that find themselves today;

And as well as to the living also to the dead: to the Brothers Grimm, to Bertolt Brecht and to Kurt Weill, to Walter Benjamin, to George Grosz, to Leni Riefenstahl, to Marlene Dietrich, to Helmut Newton and to Nico, who is buried in the forest of Grunewald, to Frank Wagner; to generations of Prussian witches, beginning with Friedrich Wilhelm’s edict of 1714, and ending with the murder of Barbara Zdunk, the Polish witch who was strangled and put on the stake on August 21, 1811; to the many Berlin women who became factory workers during WWI, and never returned to their homes; to the gangs of adolescent Wanderflegel or Wild Boys of the 1920s, William Burroughs’ inspiration; to the victims of the Kristallnacht of November 9-10 1938; to the hundreds of Jews who killed themselves in the early 40s rather than be deported from their beloved Berlin; to Berliners such as Peter Fechter, who was the first to be murdered in the “kill zone” of the Berlin wall; to those who lost their lives on what is now Potsdamer Platz, now essentially a cemetery (and let us not forget every time we walk through Potsdamer Platz that we walk among the dead); to all those who have been persecuted for their difference, and murdered; to those who suffered from abuse as children, or adults; to those who committed suicide because of their inability to live fully as who they felt they were; to those who died of HIV and AIDS; to the refugees who never made it to this safe haven of Berlin, but died along the way; to the dispossessed and abandoned; to all those who have died but cannot leave this place: I invite them to join us here, in this invocation of love; for we are a community of the living and the dead.

And what is love?

I love Berlin. But is that Love?

I love the Grunewald. But is that Love?

I love FKK. But is that Love?

Is it an accident that Art Berlin Contemporary and Anarchist Black

Cross are both called ABC Berlin? I think

not. And is that Love?

I love Berlin.

I love that there are, in the best of years, three gay pride parades, one for the gays, one for the queers, and one for the mad and disabled.

But is that Love?

I love the Berlin Philharmonic and the Philharmonie.

But is that Love?

I love Berghain and I love Lab.

But is that Love?

I love Berlin.

I love Angela Merkel. But is that Love?

I love Peaches. But is that Love?

I love Wolfgang Tillmans and Isa Genzken and Willem de Rooij.

But is that Love?

I love Berlin.

I love Südblock. But is that Love?

I love Möbel Olfe, especially on Thursdays. But is that Love?

I love Kotti. But is that Love?

I love Berlin.

I love the hipsters. But is that Love?

I love the expats and startups and coffee bars.

But is that Love?

I love that the city is a magnet for those who do not know who they are or what they want;

I love that people come to Berlin to discover who they are and what they want.

But is that Love?

Berlin is illuminated by the darkness of its past.

Berlin is illuminated by the darkness of its past.

Berlin fills me with joy.

Berlin fills me with joy.

I love you, Berlin.

I love you, Berlin.

|

|

|

| Exhibition view: Haute Culture: A Retrospective 1969-1994, ARC/Musée d'art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2011–12

Photo © Pierre Antoine | |

|

AA Bronson, on Instagram you recalled the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 90s. What similarities do you see with the current coronavirus pandemic? I was fascinated by the Covid 19 epidemic from the beginning. I think it has a lot to do with the work we did with General Idea on AIDS. But it wasn't until the people in the West started dying that I realized that my community was being targeted a second time. In the early 1990s I lost almost all my friends and acquaintances, and now it is once again my generation that is most threatened by Covid-19. The main difference is that my friends are now much younger than me, so I am the endangered species, so to speak. But there are also big differences in public interaction as opposed to the AIDS crisis... Yes. Covid-19 is being followed very closely by the mainstream media and there is a lot of coverage. Politicians are taking action, in different ways and with different success. In the case of AIDS, the disease was hardly mentioned in the media, except as a curiosity, and it took a very long time for medicine to bring about any kind of comprehensive action. Of course, the cases here in Germany occurred later than in my home country at that time, the USA, and the medical community reacted more quickly. It was the gay community that started an education program and calls for activism to get the disease under control. Only the United Nations specialized agency, UNAIDS, regularly published the frightening statistics, especially from Asia and Africa - and still does. Eventually, the pharmaceutical companies realized that there was an opportunity for huge profits, and everything changed - especially in the rich countries. Covid-19, on the other hand, already has a whole range of drugs in development. ... With what feelings do you follow the drastic measures that are currently taking effect?

Well, HIV and Covid-19 are very different pandemics. For HIV, education and medical interventions were still a long way off, and the infection was primarily sexual. A lockdown would not have helped nearly as much as the free distribution of condoms and information. Nevertheless, at that time in New York there was a kind of lockdown of rooms for sex, which in fact still exists 30 years later. Thank God Germany has a more rational and sexually positive attitude. The full interview by Saskia Trebing was published in Monopol on March 23, 2020 and can be found HERE (in German)

|

|

|

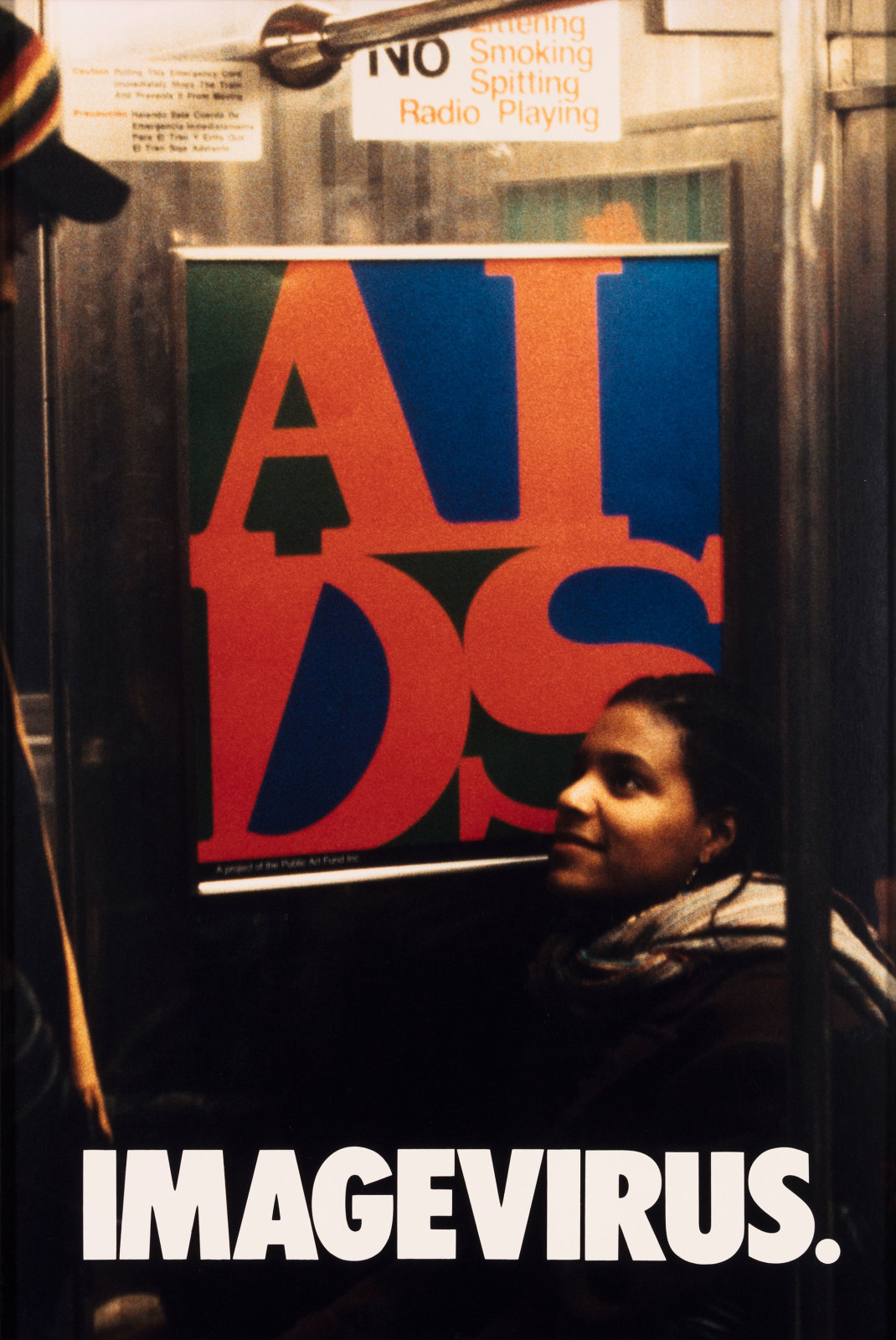

| General Idea, Imagevirus, 1989-199, (detail) signed and numbered, chromogenic prints (Ektacolor), 76 x 50,4 cm each (5 prints) (unframed)

Photo © The Estate of General Idea

| |

|

Dominic Johnson: From that ironic mode, your work with General Idea took a much more urgent turn to intervene in or comment critically on the AIDS crisis. There must have been something profoundly challenging or transgressive in transferring that ironic mode to looking at AIDS.

AA Bronson: When that moment came, we had just moved to New York. One of our best friends was very ill and we were his primary caregivers. He died in 1987, I guess. We were invited to participate in the Art Against AIDS Benefit that year, and we came up with the original ‘AIDS’ painting, appropriating Robert Indiana’s LOVE logo. We had the idea around a year earlier, but we thought it was in such bad taste that we shouldn’t do it. But because it was in such bad taste, we kept coming back to the idea. The interesting thing about the image is how memorable it is – it grabs people’s attention and it holds it. The bright colours and the reference to Indiana’s LOVE, at that moment it really felt too much. We were heavily criticised for it at the time, only by people in New York, interestingly, and mostly by the younger AIDS activists. I think people don’t realise that when we moved to New York, I was 40 years old, so we were already a generation older than many of the AIDS activists, who were in their 20s at the time. We weren’t American and we had moved in on their territory, in a sense. We didn’t go to ACT-UP demonstrations because we were living in the US illegally, and we didn’t want to get arrested and deported. There was a lot of negative feeling that we were somehow cashing in on the virus – which was not actually the case. I mean, who wants to buy a painting that says ‘AIDS’? Back then, certainly, nobody did.

Irony can be like a scalpel. It can open things up and reveal so much, and it holds people’s attention. In the US at that time, nobody – including in the mainstream art world – was really talking about AIDS. Everybody was doing their best to ignore it. We were doing a kind of publicity campaign for a word, for a name, in posters on the street and in the subway system, and billboards in Times Square. We really drenched the city. Our idea was that we didn’t want to hold copyright. We wanted to lose the copyright the same way Indiana had lost control of the LOVE copyright. Newsweek approached us because they were doing a special issue on AIDS and wanted to use the logo, so we just gave them permis- sion. They put a little logo on the corner of every page. TV shows would use it as the backdrop for discussions about AIDS. As an image, it really did act like a virus. And it was the first time we felt like all the strategies we had developed over years were suddenly focused on one thing and became tools that could be used for a particular purpose.

DJ: I saw a selection of your ‘AIDS’ paintings at Maureen Paley in 2018 and the show occurred in the midst of what may be an institutional turn towards recognising the impact of AIDS on art of the 1980s and 1990s. I’m thinking of contemporaneous museum and gallery shows by David Wojnarowicz, Derek Jarman or Gran Fury, for example. It’s important that artistic responses to AIDS are being acknowledged, but at the same time, perhaps this claiming of AIDS as simply another historically available context for art may make it seem remote, safe or disarmed?

AAB: Well, someone responded to a picture I posted on Instagram by saying I was wrong to draw a comparison between coronavirus and AIDS because nobody dies from AIDS anymore. I was shocked – if one person says it, thousands of people are thinking it. According to UNAIDS, 770,000 people died of AIDS in 2018 alone, so it’s inaccurate to see the AIDS crisis as remote. But to respond to your point, Buckminster Fuller once said that every idea takes 25 years before it can be accepted by the public. It’s been 25 years since we did those first ‘AIDS’ paintings. As the 25-year clock wound down, suddenly institutions took interest. It’s good for the public to be exposed to this history, and it’s true that it is distanced. Its claws have been removed. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I do worry about the present, and I worry about the ways in which AIDS, being something that’s mainly an issue in poorer countries, can be ignored by the richer countries.

|

|

|

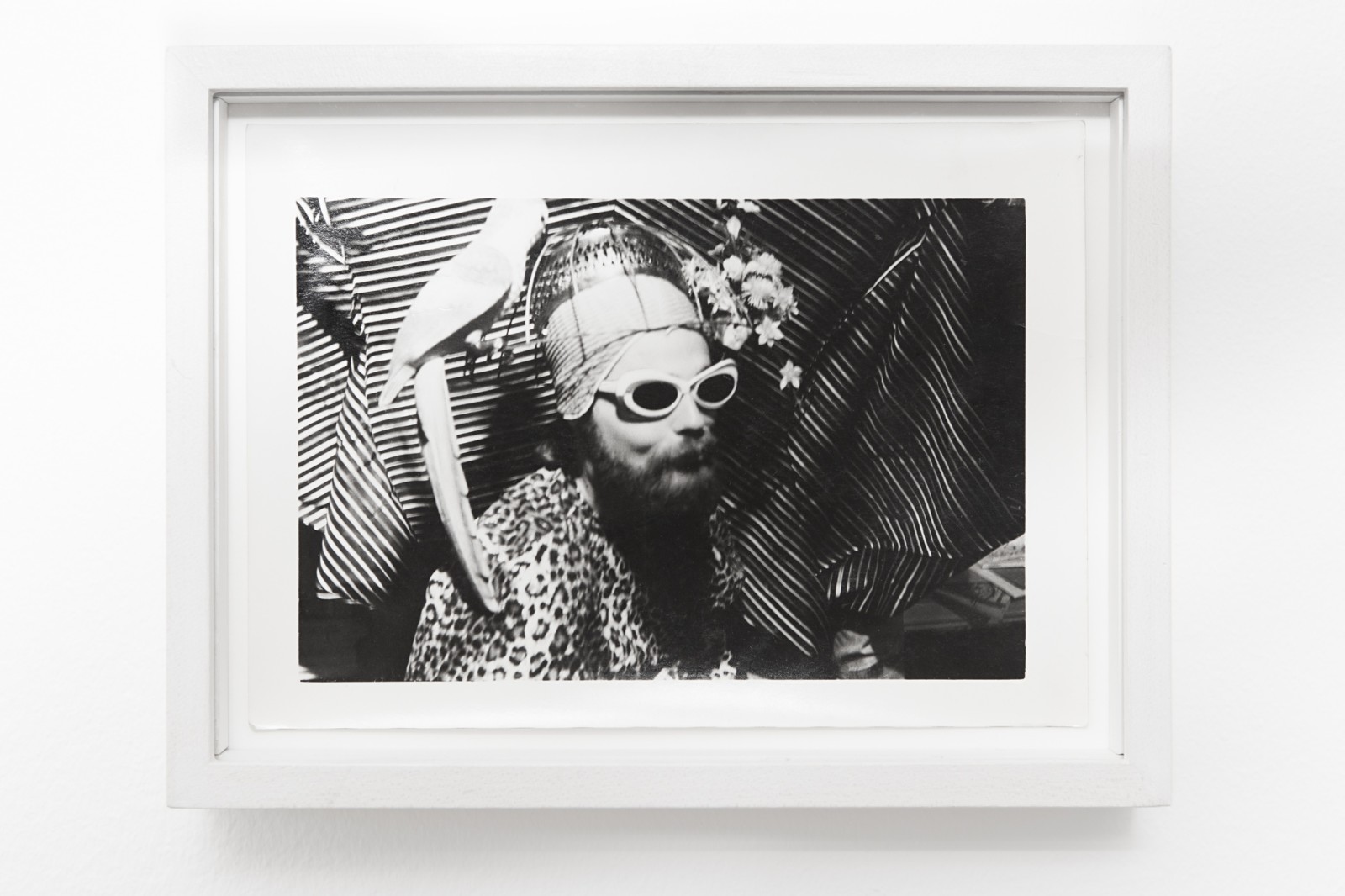

| General Idea, Portrait of AA Bronson as a Shaman, 1973, Vintage silver gelatin print, 12,5 x 17,5 cm (unframed), 15,5 x 20,5 x 4 cm (framed)

Photo © Andrea Rossetti | |

|

DJ: Since the end of General Idea, you have explored healing, spirituality and shamanism in your work, including in performance and curated events. It’s surprising, in some ways, that your work has gone from an ironic, conceptual mode to a more sincere, spiritual mode. Can you talk about that shift? AAB: Part of the reason why these ways of working are so different is that after Jorge and Felix died in 1994 I didn’t want to be General Idea. When I started working as a solo artist, I had been working for 25 years as part of General Idea. I only knew how to do General Idea. I had never been a solo artist, so I had to develop a language that could take me off on another track. Most of my training in healing practices came during the period when Jorge and Felix were still alive, and I wanted to be able to think of myself as a midwife to the dying. It was a given that they were dying, and that many of our friends were dying, and I wanted to be of service to them. Once they were gone, I thought I should make use of that service somehow, maybe by working in a hospice. But I was too burned out. Then, a few years later, with 13 certificates under my belt, I found three friends-of-friends, people I didn’t know directly, who were willing to come to me once a week or two for six months, free of charge, and I came to a point where I was confident enough in my abilities to become a professional healer. Butt Magazine did an interview and Bruce LaBruce made a portrait and suddenly I was ‘AA Bronson, Healer’. I really needed something to replace ‘AA Bronson, General Idea’, and this was it. Somehow, my image as a healer went out into the world. I began to think about Joseph Beuys, for example, and other artists who have used the subject of healing in their work. There’s quite a strong history that is generally not talked about so much. I recognised what I was falling into and decided to just go with it. The Invocation of the Queer Spirits performances with Peter Hobbs arose from the idea of healing locations and acknowledging forgotten histories of different places, and I started to broaden the subject of healing. I stopped doing any one-on-one healing work about three years ago. I’m too old, it’s too much for me. Now I joke that I do it by having tea with people – a cup of tea with me will cure what ails you. The full interview was published in the May issue of ArtMonthly and can be found HERE.

|

|

|

| Exhibition view: AA Bronson, Tent of Healing, 2013, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Photo © Ernst van Deursen | |

|

AA Bronson's A Public Apology to Siksika Nation – Ben Miller

|

|

| AA Bronson and Adrian Stimson looking at the Old Sun Residential School, now the Old Sun Community College, on the Siksika Reserve. Date: 2018. Photo © Mark Jan Krayenhoff van de Leur | |

|

Initially presented at the 2019 Toronto Biennial of Art, AA Bronson’s ongoing project A Public Apology to Siksika Nation, includes an exhibition, performative components and a publication. It responds to European genocide, including his great-grandfather’s role as the first missionary at Siksika Nation and founder of the Old Sun residential school. (Old Sun, an influential Siksika leader, is an ancestor of Bronson’s collaborator, Adrian Stimson.) Generated from ongoing dialogue with Stimson and extensive research into museum and family archives, Bronson’s project makes actionable the responsibility of settlers in the era of reconciliation.

The publication includes a text by AA Bronson, extensive archival image material and an essay by Ben Miller, who also constructed a timeline from primary sources that brings together the voices of long-gone protagonists of this story.

Below we excerpt from Ben Miller's essay Determined To Keep Up Their Dances and the J.W.Tims Timeline.

|

|

|

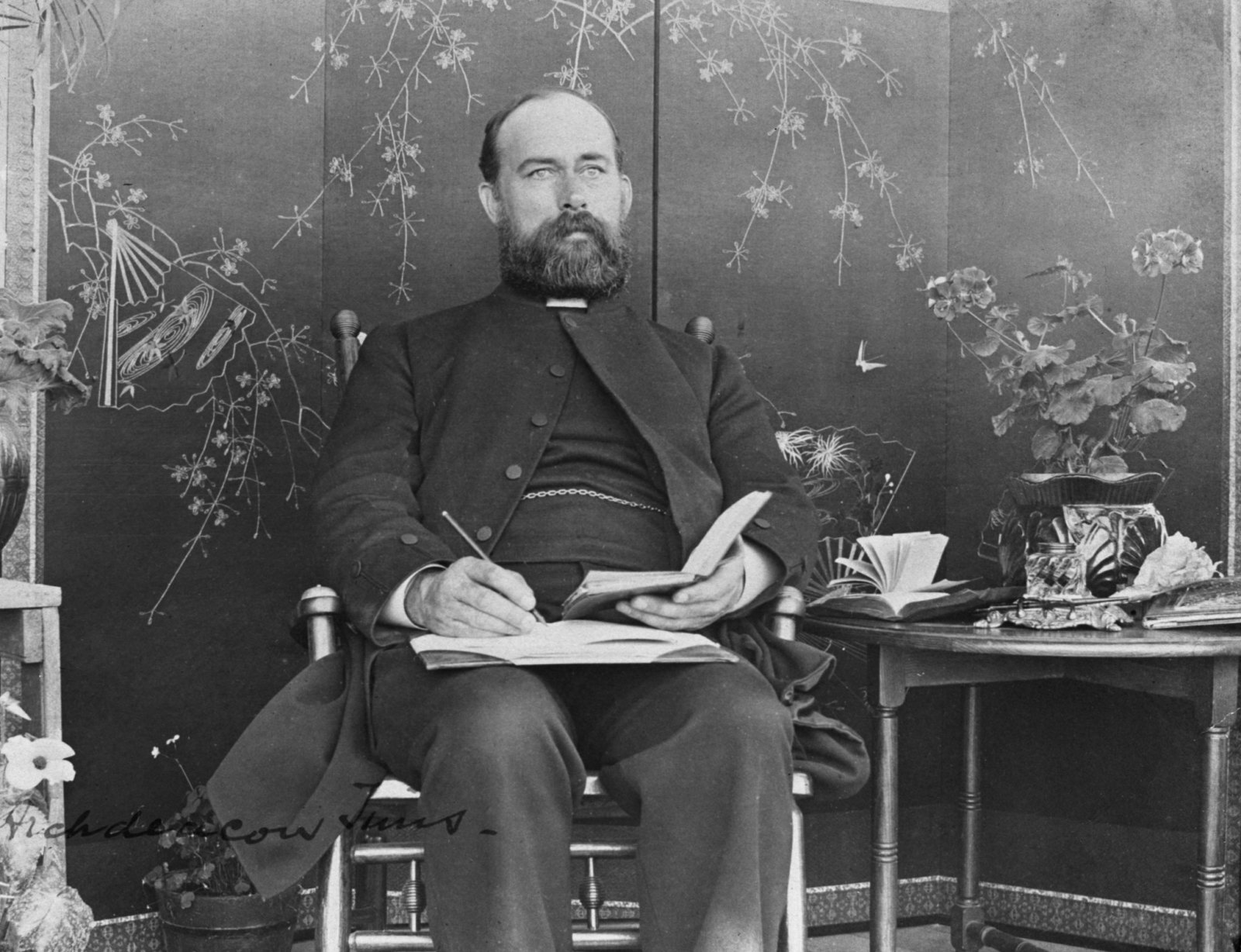

| Archdeacon John W. Tims, ca. 1896-1899. Courtesy the Glenbow Archives, Calgary, Alberta

| |

|

Determined To Keep Up Their Dances

Ben Miller

What the 1895 Siksika Rebellion and Reverend J. W. Tims’ dramatic flight from the Siksika Reserve can explain about the past and present of settler colonialism.

In 1883, the Church Missionary Society sent the Reverend J. W. Tims from seminary in Oxford, England to the western plains of Canada, as the first Anglican missionary to the Blackfoot, or Siksika, Reserve.1 Then, in 1895, he left abruptly. This essay will begin to explain why.

My introduction to this history began with a family story, a legend with deep emotional resonance across several generations. AA Bronson, the great-grandson of the Reverend Tims, remembered hearing about his great-grandfather’s time on the Siksika Reserve while growing up, saying these stories were part of the “fabric” of his family.2 His grandfather, who had followed in his father’s footsteps and run a residential school, told the following story: the Reverend Tims had been the first Anglican missionary to the Blackfoot Reserve. He learned their language, developed its written form, translated Bible verses into Siksika, and christianized the people. His was one of the first residential schools, whereby children were taken from their parents, dressed in Victorian clothing, and trained up to be little Englishmen. Due to its pagan character, he worked with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to ban the bloody ritual of “making braves,” which involved piercing the breast and dancing into trance. This, according to the family story, aroused the ire of Old Sun (1819–1897), one of the chiefs. On the day the ritual was outlawed, a “friendly Indian came to the kitchen door” and warned the Reverend to leave with his family immediately. They fled to Calgary, and the house, school, and church were burned to the ground that night. AA had never been able to corroborate the story of the flight and the fire. Now, embarking on a project of artistic research and conciliation with Adrian Stimson, the great-grandson of Old Sun, he set out to explore his family story in more depth, to probe its dimensions and meaning, and to offer his apology to the Siksika people.

Hearing this, I turned to existing scholarly material on the Siksika and Tims. The story I found there, in the work of the historian Hugh Dempsey, was markedly different. In this version, the Reverend Tims was a uniquely obnoxious and difficult man: stricter than government agents in enforcing attendance at the boarding schools he set up, a fighter in petty bureaucratic wars with little ability to work with others.3 Nothing was burned to the ground and there were no “friendly Indians” raising the alarm ; rather, several children had become sick and died in the boarding schools, and Tims had been rude to their grieving parents. He had fled under pressure from rebelling Siksika, angry state officials, and the Church itself. Despite being corroborated by more archival sources, this story also seemed frustratingly incomplete — lacking an analysis of how this particular rebellion fit into broader histories of settler colonialism, the structure of violence and profit encompassing the arrival of white people on the plains of Canada.

|

|

|

Here were two conflicting stories, equally unsatisfying in their centering of settler personalities over historical processes and Indigenous voices. I was left with many questions. How was Tims’ practice connected to the broader history of the white settling of Canada? How were land, culture, and religion connected in Siksika ways of knowing and living, and how did the arrival of missionaries disrupt those processes? How could recent thought on settler colonialism help resolve these contradictory stories and bring new meaning out of a fresh examination of the available archival material?

The story revealed by this new analysis is a micro-cosm of a bigger history. Recent scholarship emphasizes that taking Indigenous land — a process referred to as dispossession — has also required eliminating Indigenous cultures and ways of knowing. These ways of knowing emphasize relationships between people and land in ways that challenge settlers’ understanding of land as property. Robert Nichols points out that Indigenous land claims are duty-based rather than rights-based: they are a claim about responsibility to something larger than the self, that is, the Earth.4 Understanding settler colonialism’s need to eliminate these ways of knowing helps us understand how settler policies that might otherwise seem contradictory — in Tims’ case, learning the Siksika language and banning their rituals, and taking pains to educate children while at the same time allowing them to die of illness in the schools — can be understood as expressions of a single coherent historical process.5 It was not for nothing that the federal policy of subdividing reserves was described by the Canadian government in 1890 as a “policy of destroying the tribal or communist system ... to implant a spirit of individual responsibility instead.” 6

Framed by that theory, here is the story, as true as I can tell it: In 1877, the Siksika, one of four tribes in the Blackfoot Confederacy with a land claim extending across broad swaths of present-day Montana, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, had been relegated to their small reserve by the seventh treaty between Indigenous people and the British Crown, signing away the majority of their land under pressure from white settlers’ hunting-to-extinction of the buffalo. After his arrival in 1883, Tims set up a system of boarding schools in which students were forced to speak English, follow the Anglican religion, dress in Victorian school clothes, and prepare for careers as farmers and menial laborers. The students were not allowed to see their parents, even in the case of a death in the family or a Siksika religious holiday. Indigenous religious rituals, including the piercing ritual, were suppressed. After a diphtheria epidemic and recession leading to rations cuts, in the first months of 1895, at least two Siksika children died while in the gendersegregated boarding schools. This prompted a rebellion in which the rations distributor, Frank Skynner, was shot and killed by a Siksika man. Four months later, after the death of another child, Tims was forced to flee the Reserve on fear of his life. [...] |

|

|

Footnotes

1. Letter of Instruction from the Church Missionary Society to John William Tims, 5 June 1883. M1233.3, Archdeacon Tims Family Fonds, Glenbow Museum Archive, Calgary, Canada. (Henceforth “Glenbow Tims Fonds”).

2. Ben Miller, “Interview with AA Bronson about the Tims Family,” conducted 2018. AA Bronson Private Collection, Berlin.

3. Hugh Dempsey, “Scraping High and Mr. Tims,” in The Amazing Death of Calf Shirt, and Other Blackfoot Stories (Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 186–209.

4. Robert Nichols, “Theft Is Property! The Recursive Logic of Dispossession,” Political Theory 46, no. 1 (February 2018), 13.

5. Patrick Wolfe, Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event (London: Continuum, 1998), 163.

6. Canada, “Annual Report Department of Indian Affairs,” Sessional Papers, 1890, no. 12, 165, as cited in: Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 13. |

|

From The J.W. Tims Timeline

1890 ★ March 18: Letter to Tims from the Church Missionary Society sending him back to his post despite illness. (Glenbow Tims Fonds, M1233.8).

— Urged by the CMS to ignore his “ethnological and philological researches” — “do not feel bound to enter on such labors. Let them not be any burden to you. Diminish them at once, or rather even resolutely abandon them altogether, the moment you find them to occupy time which from a missionary point of view might be more profitably spent ...”

★ Spring: Sent back to post via Toronto (source: Early History of the Diocese of Calgary, written by Tims ; year unknown ; Glenbow Tims Fonds, M1233.3).

— “I visited Toronto for the first time, was nearly killed by the number of sermons and addresses I was called upon to deliver, and got back to my mission to recuperate at the end of April.

— “On my return the first Blackfoot Home was commenced and completed in the following year...”

— “While in England I met Mr. (now the Rev.) W. R. Haynes and induced him to join our staff on the Blackfoot Reserve. He came out in the fall of 1889 and joined Mr. Swainson, who had arrived the previous year, and was living in the Mission House during my absence. Together they gathered in the first six Indian boys and started the Boys Home, using the upstairs of the Mission House as a dormitory until the new building was erected, where accommodation for both boys and girls was provided.”

★ August 7: Letter requesting that he be contacted and not teachers (Glenbow Tims Fonds, M1234.3).

— “To the Indian Commissioner ... whether there would be any objection to communicating with the heads of missions instead of with the teachers direct in all matters relating to the schools?”

★ Winter Counts:

— Running Rabbit: Crow Foot Died, 25th of April, aged 60 years.

— Many Guns 68: Double Chaser.

— Many Guns 69: Crow Big Foot. — Little Chief: It was a sad year for the Blackfeet they lost their great chief Crowfoot died April 25 at the ages of 69 years.

— Little Chief 2: Our Chief Crowfoot died in April 25th all those in the tepee heard Crowfoot tell them in a little while I will go I will leave you my children be good to each other as I was good to you all mind the Red Coats because they are our friends they look after us also be kind and mind our missionaries the long coat that is what they call the Catholic priests also the short coats that is the Anglican Ministers which are also our friends I am not sorry that I am going to die I know I will go to a good place try and come to whereI will go from who where we coming from and nowhere we go be good to each other and a few minutes Chief Crowfoot left the world to God’s place.

|

|

|

| Exhibition view: General Idea, P is for Poodle, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2013

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

We are the poodle, banal and effete; note our relished role as watchdog, retriever and gay companion; our wit, pampered presence and ornamental physique; our eagerness for affection and affectation; our delicious desire to be groomed and preened for public appearances; in a word our desire to please: those that live to please must please to live.

General Idea, How Our Mascots Love to Humiliate Us, 1984

Beginning in 1981, General Idea produced a series of works featuring poodles. The image of a poodle—as a pampered, aloof creature, yet with the canine disposition of aiming to please—became an ironic alter ego of the group. General Idea adopted the poodle as iconic stand-in, in part as ironic comment on the art world and the role of the artist in it, and in part as a response to the “return” of figurative painting in the early 1980s. The group’s appropriation of the poodle played on the familiar associations with dogs (servile, ideally well-trained and loyal), with those particular to the breed, namely, its association with artificiality (on account of its traditional decorative shearing), reputed vapid aloofness and elitism as dogs of the aristocracy.

The group staged the destruction of the imagined 1984 Miss General Idea Pavillion in 1977, and became the building’s archaeologists, creating a series of sculptures, prints and paintings positioned as fragments, or ruins of the Pavillion. Small recurring figures and ornamental pattern based on the motif of poodles and their distinctive curly fur propose a fictional ancient history of the poodle iconography. The creation of shards and fragments of lost friezes and frescoes initially took the archaeological excavations at Pompeii as point of departure, especially the wall drawings in the Villa dei Misteri with its still-mysterious depictions of ritualistic erotic acts.

|

|

|

| General Idea, Pavillion Poodle Fragments Sets #1-4, 1984, plaster, paint, wood, glass, 85 x 160 x 100 cm each (4 vitrines), 63 fragments of different sizes

Photos © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

The Reading Corner – A Selection of Publications

|

|

General Idea

P is for Poodle

Publisher: Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Language: English

Available here

Co-published in part by Maureen Paley, London; Esther Schipper, Berlin; and Mai 36, Zurich. |

|

|

General Idea

Ziggurat

Publisher: Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Language: English

Available here

Co-published in part by Maureen Paley, London; Esther Schipper, Berlin; and Mai 36, Zurich. |

|

|

General Idea

Haute Culture: a Retrospective 1969-1994

Publisher: JRP|Ringier

Language: English

Available here

|

|

|

AA Bronson with an essay by Ben Miller

Edition of 250. Signed and numbered, |

|

|

Anri Sala – Kino Siemensstadt, Scharaun Online Film Screening

|

|

| Anri Sala, Answer Me, 2008, HD Video, color, stereo, duration 4:50 min

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Film still © Anri Sala | |

|

KINO SIEMENSSTADT

The image of the city in the cinematic space

Curated by Olaf Stüber and Jaro Straub

In a thirteen-week online program, the series KINO SIEMENSSTADT engages with the question of how the themes of space and architecture are reflected in artists’ films and video art today.

The series opens on Friday 29th May at 6 pm with two films by Anri Sala. Long Sorrow from 2005, filmed on the 18th floor of a residential building in Berlin’s Märkisches Viertel, creates a cinematic sightline to Berlin-Siemensstadt’s modernist settlement architecture where SCHARAUN is based.

The films will be available online at www.scharaun.de for six days, before the countdown to the next program sets in.

Programm #1, Friday May 29, from 18:00h

Anri Sala

The Long Sorrow (2005, 13 Min) & Answer Me (2008, 5 Min)

|

|

|

Karin Sander – Museion, Bolzano

|

|

| Exhibition view: Karin Sander, Skulptur / Sculpture / Scultura, Museion, Bolzano, 2020

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2020

Photo © Luca Meneghel | |

|

Karin Sander

Skulptur / Sculpture / Scultura Museion, Bolzano May 30 – September 20, 2020 Opening May 29, 4 – 8 pm A 3D virtual tour of the exhibition can be viewed hereIn her exhibitions Karin Sander humorously refers to existing situations and addresses their institutional and historical context. She intervenes in the structures of the institutions, changes them, highlights facts and invites the public to participate. The apparently familiar is rethought, it becomes the starting point of an exploratory process. Sander’s solo exhibition at Museion is designed specifically for the space allotted in the museum and will feature both existing as well as new works created exclusively for the exhibition. An artist talk with Karin Sander will mark the launch of a new publication featuring a comprehensive overview of the artist’s sculptural oeuvre, published on the occasion of the exhibition, will take place on September 18, 2020, from 6pm.

|

|

|

A paintbrush, a camera, a robot, disregarded doorstops or even an Ouija board – how much can you tell of an artist by what’s in their studio? SEE INSIDE THE STUDIO HERE

|

|

|

|

|