Willkommen: Hier finden Sie die deutsche Version unseres Briefes aus Berlin! Welcome to our Letter from Berlin! This week we take the film screening Christoph Keller’s 3 Self-Experiments as occasion to present an essay on his practice which focuses on the way in which knowledge is gathered and organized across disciplines. Please note these weekly viewing links are temporary: The films are available to view only through Sunday night, Berlin time. We also want to draw your attention to the online screening of Ari Benjamin Meyers work at the Volksbühne, a new interview with Gabriel Kuri, his reading, and a podcast on Julia Scher’s Security by Julia. Anything you may have missed from our social media channels can be found on Continuity, our digital platform. Read this in good health.

|

|

|

Christoph Keller – 3 Self-Experiments – This weekend's film screening |

|

| Christoph Keller, Whirling until I drop, 2008, 5 min, B/W, no sound, from 3 Selbstversuche, 2008, digital video (3 films) | |

|

Whirling until I drop, 2008

In this video work, I can be seen filming myself - apparently with the camera suspended from the ceiling - in the act of beginning to rotate on my own axis. My gaze remains focused directly at the camera. I spin around for five minutes, until finally, when my movements become uncontrollable due to dizziness, I fall to the floor.

Let it out - babbling, 2008

In this video, I begin speaking quickly and spontaneously without any definite purpose. Whether regarding its spoken contents or its progression, this test was not preceded by any preparations. The language is English.

Faint through hyperventilation, 2008

The work consists of 5 versions of an autoexperiment in which I enter the image, crouch down, hyperventilate 7-10 times, and then stand up and press down suddenly on my solar plexus with both hands. As a consequence, I lose consciousness and collapse in a faint in front of the camera, where I lie motionless, each time for approximately 10 seconds. As soon as I have regained consciousness, I turn directly toward the camera and speak about that which I have just experienced

Christoph Keller

"Don’t try is at home!" is what people used to say on television, when people still watched TV. Now everybody is trying everything at home and posting it everywhere. Suggestions for self-experiments abound.

But self-experimentation has a very long history. It takes up a rather scary chapter in the history of scientific discovery, especially medicine, ranging from the relatively benign to the catastrophic, from studying the afterimage created by gently pressing on one’s eyes to injecting yourself with animal blood, syphilitic pus or—preferable in this list—cocaine. The last substance was the subject of Sigmund Freud’s extended self-experiments and it seems from a casual survey that nineteenth-century neurologists and physiologists were certainly some of the most prolific (self-)experimenters.

The modern “experimentalization of life“, in a term coined by a major research project in the history of science to describe a process in European intellectual history that began around 1800, and led to the reconfiguration of science, art, and technology, transcended the quest for scientific breakthroughs and influenced many other areas of intellectual and artistic production.

As the research group put it: After experimental physiology had established itself as one of the paradigmatic disciplines of the nineteenth century, psychology and linguistics also became laboratory-based enterprises. Experimental cultures emerged thereafter in a variety of places, as for example in literary movements relying on automatism, aleatorics, and combination. New media such as photography and film transformed the fine arts and the sciences. Cities became vast fields of experience in which people undertook all sorts of experiments in living.

It is this legacy, both the daring self-experiments of early 19th century physiologists and later avant-garde artists that is evoked by Christoph Keller’s short films. His interest in scientific methodologies is further discussed in the introductory text on Keller’s practice below.

—Isabelle Moffat |

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Encyclopaedia Cinematographica, 2001 (detail), 40 DVD's with looped motion sequences of 40 animals, shown on 40 monitors | |

|

The blind spots of our thinking interest me.

Christoph Keller

Christoph Keller’s practice coheres around the question of how we know what we know. His works articulate his continuous artistic inquiry into the mechanisms of how knowledge is accrued, transformed from observation and sensation into belief, shaped by explicit or tacit assumptions, and, finally, organized into models. Taking on different roles—among them, naturalist, explorer, scientist, occultist, journalist, test subject—Keller in his work invokes, reconstructs, sometimes enacts, charged moments in the history of science, of scientific models, and their utopian visions. Comparable to extended case studies in science, his projects develop from the artist’s investigation of other disciplines and partial immersion into their diverse methodologies. His installations, which often recall experimental set-ups, translate his findings into the context of his own artistic thinking and to the spaces of art exhibitions as privileged sites of observation and analysis.1

A specific emphasis has been on the history of science, especially forgotten or marginalized pockets of knowledge. Several of Keller’s installations, films, or photographic projects engage with existing historical entities: literary works that internalized philosophical models, the psychological interests of a tight-knit artistic avant-garde of 1920s Berlin, a found medical archive, or an abandoned behaviorist film project from the 1950s.2

More often the artist chooses oblique scientific inquiries as the focus of his artistic surveys, enacting moments of discovery in which the entanglements of scientific method, technological apparatuses and mythic structures are given shape, making apparent the reciprocal indebtedness of disciplines. These moments show the constant ebb and flow of scientific models, the fickleness of epistemological standards and its shifting parameters—changes that can make one scientist famous for his rigor while another may drift from former respectability into marginalization. Acting as archeologists of such instances of intellectual drift, Keller has said: “…some of my works could be seen as an attempt to reactivate modes of subjectivity and of existence that have been displaced or marginalized by mainstream science.”3 |

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Cloudbuster Project, 2003, Clocktower Building, New York | |

|

Keller’s work finds precisely calibrated formats that appear to resonate with the subject of his projects—a sculptural recreation & enactment of the Cloudbuster apparatus devised by Wilhelm Reich, a documentary with extensive interviews & curatorial project, or an installation of a suspended mirrored spiral in reference to a literary take on expanded consciousness with audience participation in an experimental component.4

The practice of an artist working radically across many mediums may be a challenge for an audience, even as the traditional separation between painting and sculpture, photography and print has become more fluid. While the definition of what constitutes an artwork continues to expand and the concept of medium specificity has been widely contested, the engagement with the specificity of a medium has surfaced as important mark of artistic sophistication and rigor. In her groundbreaking 1978 essay, art historian Rosalind Krauss wrote: “But what appears as eclectic from one point of view can be seen as rigorously logical from another. For, within the situation of postmodernism, practice is not defined in relation to a given medium—sculpture—but rather in relation to the logical operations on a set of cultural terms, for which any medium—photography, books, lines on walls, mirrors, or sculpture itself—might be used.”5

Artists such as Keller who choose to deliberately employ the specificity of a medium according to each individual project appear especially attentive to a medium’s highly charged histories of forms, significance of technological methods, and the plethora of art historical, cultural and social connotations. At its most reflective and conceptually nimble, this approach of articulating each project through a formal execution appropriate to its conceptual basis, allows Keller to employ a medium as richly connotative sign. |

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Ceppo Sradicato (series of black and white photographs), 2019 (detail), gelatin silver print on Ilford warmtone paper, 38 x 56,5 cm each (unframed, 7 parts) | |

|

| Exhibition view: Christoph Keller, Hito Steyerl, Tao Hui, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2019

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

| |

|

For Keller working with multiple mediums has become an integral part of his practice, incorporating their associative histories and contiguous meanings into the projects. This might include epistemological models from diverse and distinct disciplines: anthropology, behavioral theories, physics, the history of science, fringe or pseudo scientific explorations, or the development of technological apparatuses and media studies. The formal heterogeneity coheres around the artist’s rigorous attention to the structural logic of each operation: form, medium, installation, and conditions of display are carefully coordinated, their individual connotations orchestrated to achieve coalescence while still preserving the works’ openness.

The artist’s sustained thinking about media and photography (perceived in its theoretical definition as a practice that, along with the givens imposed by its technological apparatuses, also determines the conditions of its production, distribution, and reception) exemplifies Keller’s play with the complex associations of a medium. Combining elements of the photographic and cinematic, in his early career Keller invented processes for recording time photographically: devising cameras that transported the film during exposure, creating what the artist called Rundumbilder (all-around pictures) that registered movement and by implication time. Working to overcome the limitations of the medium—influenced by experimental and structuralist filmmakers such as Bruce Connor, Maya Deren, or Stan Brakhage—the apparatus determined the parameters of the formal outcome.6 The images seem to dissolve the photographer’s perspective into a temporal continuum, a technologically assisted process that invokes psychological operations, namely the dissolution of an unchanging self, and an awareness of its motion in time and space. The extensive series of Rundumbilder photographs—almost constituting an archive itself—addressed contemporaneous theoretical discussions, such as the indexicality of photography, the durational condition of cinema, the experiential aspect of viewing art, and the dissolution of the authorial subject.

|

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Menschen am Alex, 2000 (detail), signed, Lambda-Color, 13,2 x 123 cm | |

|

Yet apart from the images themselves, the construction of the apparatuses, their development and subsequently their registry in 1995 as patent—a deliberate artistic gesture to inscribe the work into the patent office as if it were a museum—were crucially integral parts of Keller’s project.

In the documentation of his projects, another aspect of time is encapsulated: the photographs act as records of an artistic project, thus implicitly articulating in-between-spaces and constructing a narrative logic. The photographs introduce additional layers of meaning that supplement the installations and stand alone as coherent work. Thus, for example, the act of transferring the stump of a Roman tree into a gallery context is encapsulated in a suite of images that far exceeds mere documentation and becomes a charged sign of historical, social and artistic transformation.

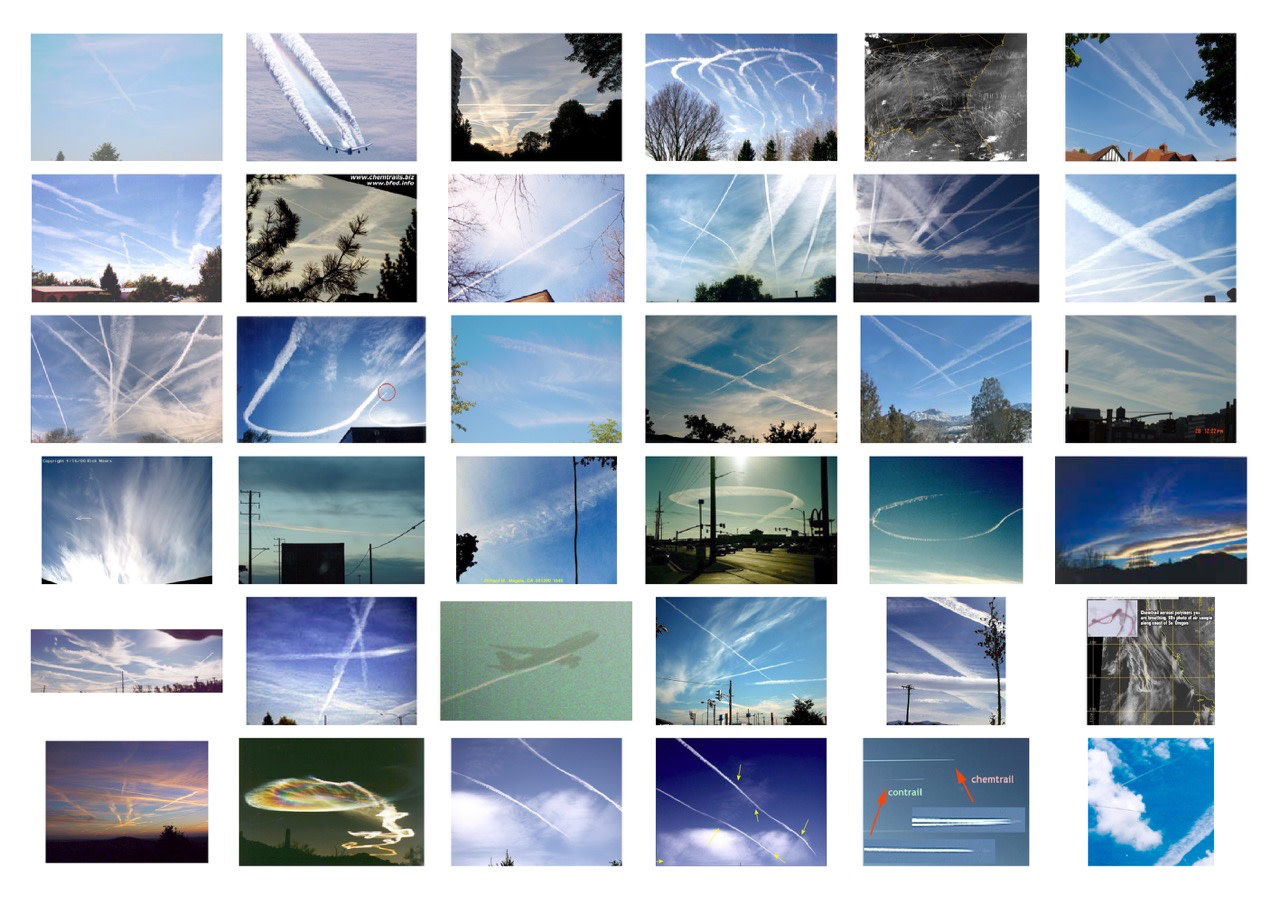

Other photographic projects, such as Keller’s appropriation of archival material installed in gridded, formal arrangements, or his cinematic compilations, invoke an important aspect of structuralist linguistic analysis: the repetition signals to the viewer that raw matter is being transformed, given shape and meaning. While the ordering function of the grid as formal display of images of “Chemtrails”, for example, or photos of US embassies around the world suggests a rationalist approach, the conspiratorial content of the images runs counter to rationality and resists the imposition of order. Creating a subtle tension, these works make palpable both the violence and the instability of classifications.

|

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Chemtrails-Project (1-3), 2006, grid of C-Print on paper, 72,7 x 103 cm each (framed, 3 parts) | |

|

Keller has described his work as “offene Wahrnehmungsvorschläge” (open proposals for perception). His research and investigation into a cultural context of specialized pockets of expertise remains free of value judgment. Knowledge is transmuted without relinquishing its richness, ambivalence, contradictions, and complexity. Works reach into the past and the future, invoking its contexts rather than proposing a hegemonic authorial position and closure. Neither didactic nor tied to any ideological position, the openness of this approach is part of a practice that entails a lived open-endedness of interpretation, continuously accruing additional meaning.

The observer becomes part of the experimental set-up of Keller’s works. Engaged as active intellectual inquirer, he or she is sometimes made complicit in positions of power or loss of control: posed as ostensibly scientific observer, judgments are subsequently called into question by subtle disruptions that arise from engaging with the work. Comparable to the literary trope of an unreliable narrator, Keller’s works create situations that carefully destabilize customary viewing positions: Be it literally invoking an empathic loss of control from watching test subjects getting high on laughing gas, observing the artist spin around his axis until he passes out, or becoming complicit with a colonizing gaze watching anthropological footage.7

While engaging the viewer in tacit or explicit ways, Keller remains fully cognizant of his own position in this dynamic. A model for such a discursive exchange with his audience/the viewer is also integral to the works; found in his dialogues, conversations and collaborations with others, be they artists, scientists, researchers, or experts of all kind.8 Both his subjects and the audience are always addressed as an equal, their autonomy assured. Indeed, Keller’s willing adoption of different roles, as producer of objects, anthropologist, journalist or test subject, surfaces as a subtle self-reflectiveness, a mindful acknowledgment of the self-seriousness shared by artistic and scientific inquiry.

Keller’s oeuvre addresses science and myth, technology and notions of the self, engaging the viewer in an ongoing, open-ended artistic dialogue that transforms the gallery/exhibition space into a site of experimentation, a discursive space of shared inquiry.

– Isabelle Moffat

|

|

|

| Christoph Keller, Verbal/Nonverbal, 2010, single-channel HD video, duration: 20 min | |

|

Notes

1) Keller has used the term “observatorium” to describe this aspect.

2) See his 2015 exhibition Grey Magic on the theory of “eccentric sensation” in Ernst Marcus and Salomo Friedlaender/Mynona, Retrograd-a reverse chronology of the medical films made at the Berlin hospital Charité 1900-1990 (1999/2000), and Encyclopaedia Cinematographica (2001).

3) Paranomia, 2018, p. 36.

4) See Cloudbuster Project (since 2003), Small Survey of Nothingness (2014), the exhibition Aether—from Cosmology to Consciousness at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2011 and Grey Magic.

5) Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, MIT Press, 1985, p. 288.

6) Exhibited at the first Berlin Biennale, the 10,5 meters long Rundumbild S-Bahn created a disorienting spatial experience based on visual registering a temporal process.

7) See Verbal/ Nonverbal (2010), Whirling until I drop (2008), Shaman-Travel (2002).

8) This emphasis recalls Keller’s activity in artist collectives in post-1989 Berlin. Distinct from the experience of artists trained in the master classes of the German art academies, the 1990s Berlin scene was characterized by a collectivist search for new artistic and intellectual frameworks. Informed by the redefinition of artistic practice and the interrogation of notions of authorship, authenticity, intentionality and exhibitions as displays of concrete objects, Keller’s circles had no masters and instead, perhaps rather in a late resonance of Berlin Dada, engaged in collective discourse, political discussions and actions. |

|

Christoph Keller

Paranomia

Contributors: Bernard Blistène, Horst Bredekamp, Jimena Canales, Sarah Demeuse, Heike Catherina Mertens, Ana Teixeira Pinto, Manuel Raeder, Detlef Thiel, Joseph Vogl, 2016

Softcover

Publisher: Spector Books

Language: French, English

Available here

|

|

|

Ari Benjamin Meyers

Tacet in Concert

Publisher: Corraini Edizioni

Language: English, with Italian insert

Available here

The first artist's book by Ari Benjamin Meyers, Tacet in Concert is conceived as the final chapter of a three-part project, and completes the journey begun with his two solo exhibitions: Tacet and In Concert. Very different in content and presentation, the two shows were held almost consecutively during 2019, the first at Kasseler Kunstverein and the other at OGR Turin. |

|

|

Tune In – Gabriel Kuri – Bedtime Stories, The New Museum

|

|

Only a few weeks ago, Gabriel Kuri wrote in our Letter from Berlin about his love of books. Now he has recorded a story by Umberto Eco as part of the New Museum's series Bedtime Stories (in English and in Spanish).

|

|

|

Tune in – Ari Benjamin Meyers – Volksbühne Online Streaming

|

|

| Photo © Joachim Koltzer

| |

|

Forecast (Part I/Concert Version)

by Ari Benjamin Meyers

American artist and composer Ari Benjamin Meyers works at the intersection of music, theatre, performance and live installation, aiming to exploit each genre’s particular register and make new connections between their different mechanisms of action.

Forecast, his work that was scheduled to premiere on April 23rd but whose rehearsal process and premiere had to be postponed to next season due to the coronavirus pandemic, is dedicated to the weather as phenomena and a starting point for an evening about predictability, and humans as the creators of the future with their need for forecasts, control and imagination.

From May 11th-15th, the Forecast ensemble met in the Volksbühne to record an excerpt of the performance as a concert-style session on video.

(Text: Volksbühne)

|

|

|

Tune in – Podcast on Julia Scher's Security by Julia

|

|

| Julia Scher, Security By Julia IV, 1989, performance

Exhibition view: Security By Julia IV, Whitney Biennial, New York, 1989

Photo © Julia Scher | |

|

In this podcast series Prof Dr Astrid Mania, students, and colleagues from HFBK in Hamburg as well as special guests talk about art works that resonate with what’s currently on our minds, that might be thought-provoking, comforting and also a little entertaining every now and again. In this fifty-second episode Astrid Mania talks about Julia Scher's Security by Julia.

|

|

|

The Art World Works From Home – Gabriel Kuri

|

|

| A view inside Gabriel Kuri’s studio | |

|

|

|